A Naturalist Escapes into Open Air

Richard Fortey's message was: "Be curious." Also leave time to just quietly watch.

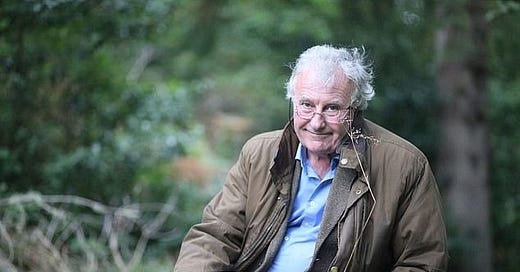

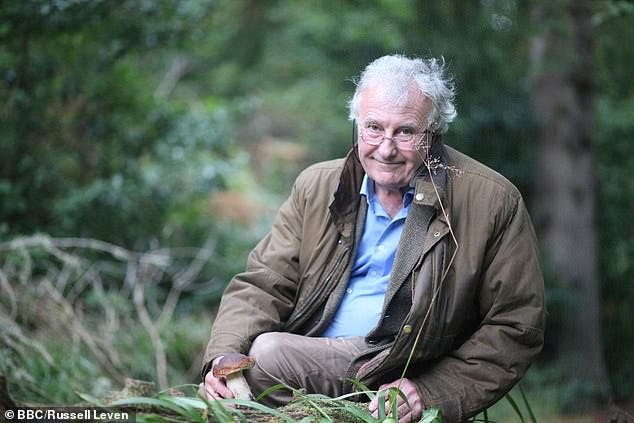

I just got word that the British naturalist and author Richard Fortey died, last Friday, at age 79. I knew him from his books, notably Dry Store Room No. 1, about the secret life of a natural history museum, and The Wood for the Trees, a 2016 account of the green pleasures he found, on retirement, in a nearby patch of woods. I reviewed the latter for the Wall Street Journal, and I am reprising it now as a memorial and also as a memento mori on living well in whatever time we may have remaining.

When Richard Fortey, a paleontologist, popular writer and television presenter, retired a few years ago after a long career at the Natural History Museum in London, he took it as a chance to “escape into the open air.” No more specimen rooms, no more staff meetings. The proceeds from a TV series proved just enough to purchase 4 acres of “ancient beech-and-bluebell woodland” in the Chiltern Hills, near his home in the London suburb of Henley-on-Thames.

In the past, Mr. Fortey had undertaken ambitious schemes, like a sprint across four billion years of evolution for his 1997 book, “Life: An Unauthorized Biography.” Now he set out to explore “a tiny morsel of a historic land.” The previous owner had divided off pieces of Lambridge Wood, part of an old estate, and the buyers—including a retired virologist, a professional harpsichordist and a founding member of the band Genesis—each separately purchased a piece “to prevent the wood from being felled or turned into housing.”

For Mr. Fortey, his patch, dubbed “Grim’s Dyke Wood,” became a place to sit on a log, eat a bacon sandwich and contemplate mosses, a predatory fungus, crane flies, springtails, an “almost elephantine” weevil and whatever else passed by, or just stood still, through each season. In “The Wood for the Trees: One Man’s Long View of Nature,” he tells the story from April of one year through March of the next.

This sort of thing—the microcosmic exploration of one farm, forest or village—is almost a genre in the British Isles, dating back at least to Gilbert White’s 1789 “Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne.” Thankfully, Mr. Fortey doesn’t pretend to be treading virgin territory either in literature or in his forest. But he makes the genre a fine playground for his characteristic blend of wide-ranging curiosity, deft observation and deep research.

His heart is in the intimate examination of nature, but he pursues this passion without sentimentality. “The wood,” he writes, “is not eternal—it is a construct, a human product. It was made by our ancestors, modified repeatedly, nearly obliterated, rescued by industry, forgotten and remembered by turn. . . . The natural history was part and parcel of the human history.”

He is happy to recount the long exploitation of these woods, from the ship builders of the British navy on up to the latest gasp of commercialism—a modern trade crafting brooms out of tightly bundled birch twigs for real-life games of Quidditch played by overzealous “Harry Potter” fans. He even gives thanks, a little ruefully, for pheasant-shooting: “Were it not for this sport of the well-to-do or well-connected, many more beech woods would probably have been cleared by now and put down to barley.”

The writing is wryly erudite. On accidentally and agonizingly rubbing milky sap from the stately wood spurge plant in his eyes, Mr. Fortey notes: “I cannot recall such a painful reaction since they closed my favourite Chiltern pub (the Dog and Badger).” He also confesses to a passing “piece of wickedness.” Leading a tour of local mushrooms in October, “the glory time for a fungus-lover,” he is irritated by a philistine who wants to know only, “Can you eat it?” When the question comes yet again as Mr. Fortey is digressing on the wonders of Lactarius pyrogalus, whose name means “fire milk,” he replies: “No, but you can taste it.” His tormentor does so, and thus he buys an hour of silence.

Mr. Fortey brings more investigative tools to Grim’s Dyke Wood than most amateur naturalists could muster. At one point, a machine on caterpillar tracks makes its way into the wood, sets out its stabilizing legs, and sends a platform on a telescoping shaft up 80 feet to reveal the canopy of the beech trees. For a moment I had a sinking fear that a new television series was already in production. But it turned out to be a project led by a team of entomologists from among Mr. Fortey’s old colleagues at the Natural History Museum. They found that elephantine weevil and also a brilliant iridescent green jewel beetle of a sort more commonly seen in tropical rain forests.

In one of his best passages, Mr. Fortey weaves the hunt for some rare plants (a ghost orchid and a cousin of our Indian pipe, called the Dutchman’s pipe in the U.K.) with the story of rumored ghosts at a local cottage, the scene of a shocking 19th-century murder. The ghost stories are “all nonsense, of course, as every rationalist will agree,” he concludes. But then he adds: “I have been in the wood on an overcast, windy evening late in the year when I heard a sudden brief, distant cry—it must have been a red kite out late, or even a frightened blackbird. . . . Ignore the sudden shiver. Let’s not be silly.”

The book is less successful, though, in its supposition-heavy attempts to fit Grim’s Dyke Wood into the larger scheme of history: During the Civil War of the 1640s, Mr. Fortey writes, the cries of rowdies “would have carried to our wood from the other side of the valley”; an earthquake in 1683 probably “shook all the trees in Lambridge Wood”; and on an 1828 tour of the area, John Stuart Mill might or might not have “walked exactly along the footpath past our wood.”

I was also a little dismayed, roughly a third of the way into the book, when a heavy rain sends Mr. Fortey scurrying back to his car, to learn that he doesn’t necessarily walk to his bit of woods. Being unsentimental is one thing, but driving somehow spoils the enterprise (at least for the reader judging from the comfort of his living room).

Even so, the book sets an excellent model for people wondering whether there should not be more to life than the necessary round of getting and spending followed by endless click time in front of the television set. “If I could issue one injunction to humankind,” Mr. Fortey writes, “it would be: ‘Be curious.’ ” But he seems equally content just to get us quietly watching. At one point, he quotes a 1911 poem called “Leisure” by W.H. Davies, who asks: “What is this life / if, full of care, / We have no time to stand and stare. / No time to stand beneath the boughs / And stare as long as sheep or cows.”

With that bovine image in mind, I set down Mr. Fortey’s book, abandoned the living room, and went outside to see, hear and smell (but perhaps not taste) the very lively world of plants and animals in my own backyard.

Richard Conniff’s latest book Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion comes out today in paperback. His other books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. He also mostly drives to his walks in the woods.

great profile. I can relate in many ways! Look forward to reading Mr. Fortey.