by Richard Conniff

Excerpted from Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time (W.W. Norton)

Out in the Okavango one evening, McNutt and I are talking about dogs and doing our best not to think about all that. Probably we should be savoring all that is sublime and unfettered about wild dogs in their natural element. But the truth is that for the moment we are just having having a good time. We joke about the sly twist of destiny that caused three brothers from the Painters pack (Braque, Bacon, and Rothko) to hook up for a time with the Four Females from Hell, before settling down with a trio of females named for single malt whiskeys (Tamdhu, Islay, and Talisker). It occurs to me that following the different packs as their lives unfold must have a soap-opera feeling for him.

"The thing that motivates me most to find tracks and stay on them all day and go out again the next day,” he says, "is to find out if it's one of the hundreds of dogs I've come to know. You've been with their mothers and fathers when they were born, and you see them grow to reproductive age and then disperse and disappear. When you find them again, it's exciting.”

”So tell me about the Four Females from Hell,” I say. Their names, he says, were Trumpet, Viola, Tympany, and Bell, and at various times he saw them with seven different groups of males, several of which died or disappeared soon afterward. Among the suitors, somewhere between The Painters and Toto from the Wizard of Oz pack, was a male named Piccolo. “Then the Females disappeared,” McNutt says, and after two years he figured that lions or farmers had killed them. But one day a new pack showed up in his study area and it dawned on McNutt that the male was Piccolo and the female was Bell.

"I found them hanging out together with yearlings,” he says. They had become the parents of Ditty, the same dog that sniffed at the back of my neck, and Lyric and Chorus, who did not eat me. “At least one of the Four Females from Hell had successfully reproduced and stabilized,” McNutt says, gratified, with an ”I knew the bride when she used to rock-and-roll” sort of smile.

Later, a solo male showed up on the fringes of the pack, and it turned out that McNutt knew him, too. His name was Newkie (short for Newcastle), a Beer-pack dog whose older brother had once courted the Four Females from Hell. Newkie also had a history in McNutt's notebooks. McNutt had watched him grow to reproductive age and then strike out on his own. While he was away, an epidemic hit the Beer pack, possibly rabies or canine distemper picked up from a villager's dog. ”Newkie came back and found everyone dead,” McNutt says. He settled into his old habitat, finding solace for his social nature in the scent marks of his pack, which lingered like ghosts for months afterward. Then he began to Shadow the Music pack, hoping to lure away Ditty, or possibly to replace Piccolo as the dominant male. Ditty showed no interest, and Piccolo repeatedly pushed him off. But McNutt noticed that Piccolo's rebellious son Riff sometimes ran interference for Newkie against Piccolo. Now Riff had actually left his home pack to join up with Newkie. Together, says McNutt, they have a better chance of attracting females than either of them would on his own.

But this is as far as the story goes this evening. McNutt cannot say if Newkie will get a girl, or if Ditty will finally strike out on her own, or if Bell and Piccolo will grow old and dowdy together. He will have to stay tuned for the next episode. We watch the birds known as quelea come rolling into their evening roosts, undulating like swarms of insects above the marsh. A couple of red-necked falcons pick off stray birds to eat for dinner. In the distance, a hippo sounds its sonorous bassoon note.

The Land Rover turns back to camp, and it occurs to me that the lives of the dogs are as messy and tangled as our own. As rich with the tidal coming and going of generations. McNutt is wheeling around trees and stray elephants, muttering, "Uh-oh, Uh-oh,” and I am thinking about another night when I watched a litter of yearlings playing in the dark. A half dozen of them chased each other in a tight circle around a sage bush, diving into the middle and then shooting out the sides. They jaw-wrestled and played tug-of-war with one another. They made mock charges and danced apart, and then stood with mouths slightly opened, eyes bright, seeming to grin. One paused to catch his breath, as if having called time out. Then he crept up to pounce on a litter-mate, and set the chase going again. All this took place, like almost everything wild dogs do, in silence. The sounds we heard in the darkness were the dry rustling of the bush, the huffing of the dogs' breath, the soft, horselike thumping of their foot pads on dry earth. A person passing by 50 feet away might have thought there was nothing much going on out there.

We left them like that, dancing together in the darkness. "You always leave wanting to come back,” a friend had told me. With luck, the dogs might still be there if I ever got the chance. They would be lying in their doggy heaps or hunting like dappled shadows at dusk. Better to think about that, I figured, than the other possibility, which is that soon there may be no wild dogs at all.

END

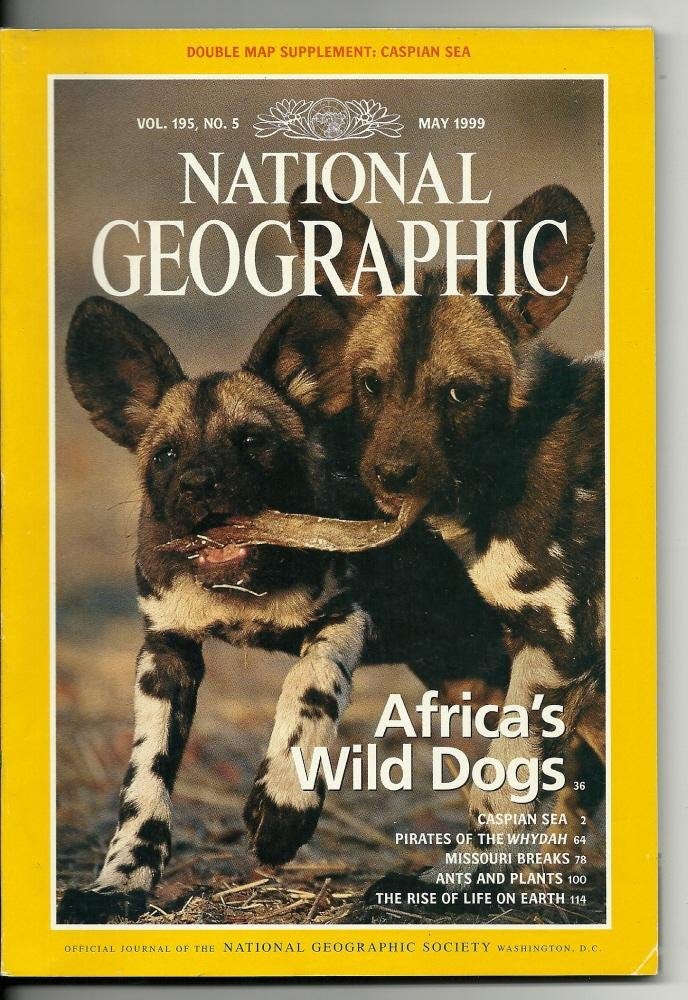

P.S. One reason I treasure this story is that National Geographic put it on the cover, with a great photos by Chris Johns and Dave Hamman. Both of them had become friends over the course of the research, not a common result when writers and photographers get thrown together in the field.

The story attracted attention at a time when African wild dogs were still tainted by bloody-minded lore and relatively unknown to the outside world. I like to think this story helped encourage donors to fund wild dog research, tourists to want to see them, and safari lodges and reserves to value having them.

Today, more than a quarter-century later, the African wild dog population in the field has risen to 6600 individuals. That’s not enough, of course. They occupy only 14 of their original 39 countries, and now face increasing threats from genetic isolation and climate change. But it feels good to have improved the wild dog’s chances in the wild, at least for a time.

These days National Geographic is a shadow of what it was then. Like every other magazine, it struggles to find the resources to put writers and photographers on the scene to report stories like this. Your support for my work, as readers and also, if possible as paid subscribers, is a significant help.

From Dave Hamman, via email: "I wholeheartedly agree with your final paragraph and I know for a fact that it did have an impact on the research ( especially the funding side) and on tourists. I've seen the change. So many guests come to Botswana specifically with the hope of seeing the dogs."

Such a great story! Fascinating.