By Richard Conniff

A few years ago, researchers were doing a routine review of camera trap footage from the National Key Deer Refuge on Big Pine Key, Florida. The ordinary traffic passing in front of the camera included a couple of raccoons. But then a key deer, a roughly half-size subspecies of the common white-tailed deer, made eye contact with one of the raccoons.

As if by agreement, the racoon immediately walked up to the deer, took its face in its hands, and began nibbling. When the raccoon sat down briefly as if to scratch itself, the deer patiently waited until it rose up again on its hind legs and resumed feeding.

“The raccoon was really using its incisors to pluck something from the deer’s face,” says Michael Cove, a mammalogist at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science. “You can see it.”

In a paper Cove and his co-author later published, they theorized that the raccoon was removing ticks or other external (or ecto) parasites that normally afflict key deer. It was a cleaning partnership, providing food for the raccoon and relief from bloodsucking pests for the deer, an endangered species with perhaps 1000 individuals surviving in the wild.

These cleaning partnerships are everywhere in the natural world. Hippos, for instance, are constantly having their ectoparasites picked off from above by the birds known as oxpeckers, and from below, by fish working their toothy way along the hippo’s legs and underbelly. Darwin’s finches and scarlet crabs provide roughly the same service for marine iguanas in the Galapagos. On the African plains, warthogs seeking relief from unwanted fellow travelers visit what the BBC has archly termed “the mongoose spa.” Camera traps now reveal new examples of cooperation between unrelated species every year.

Even bats on the wing seem to get in on the act. In summer at a reserve just north of Minneapolis, the biting insects called deerflies swarm white-tailed deer. Bats take notice and at the height of the deerfly season, routinely make foraging sorties just above the deer.

An individual bat can consume hundreds or thousands of insects a night, researchers note, and concentrating on the cloud of insects around the deer reduces the time needed to hunt them. The deer also seem to benefit, as “even a single associating bat could potentially cause a sizeable reduction in the pest load.”

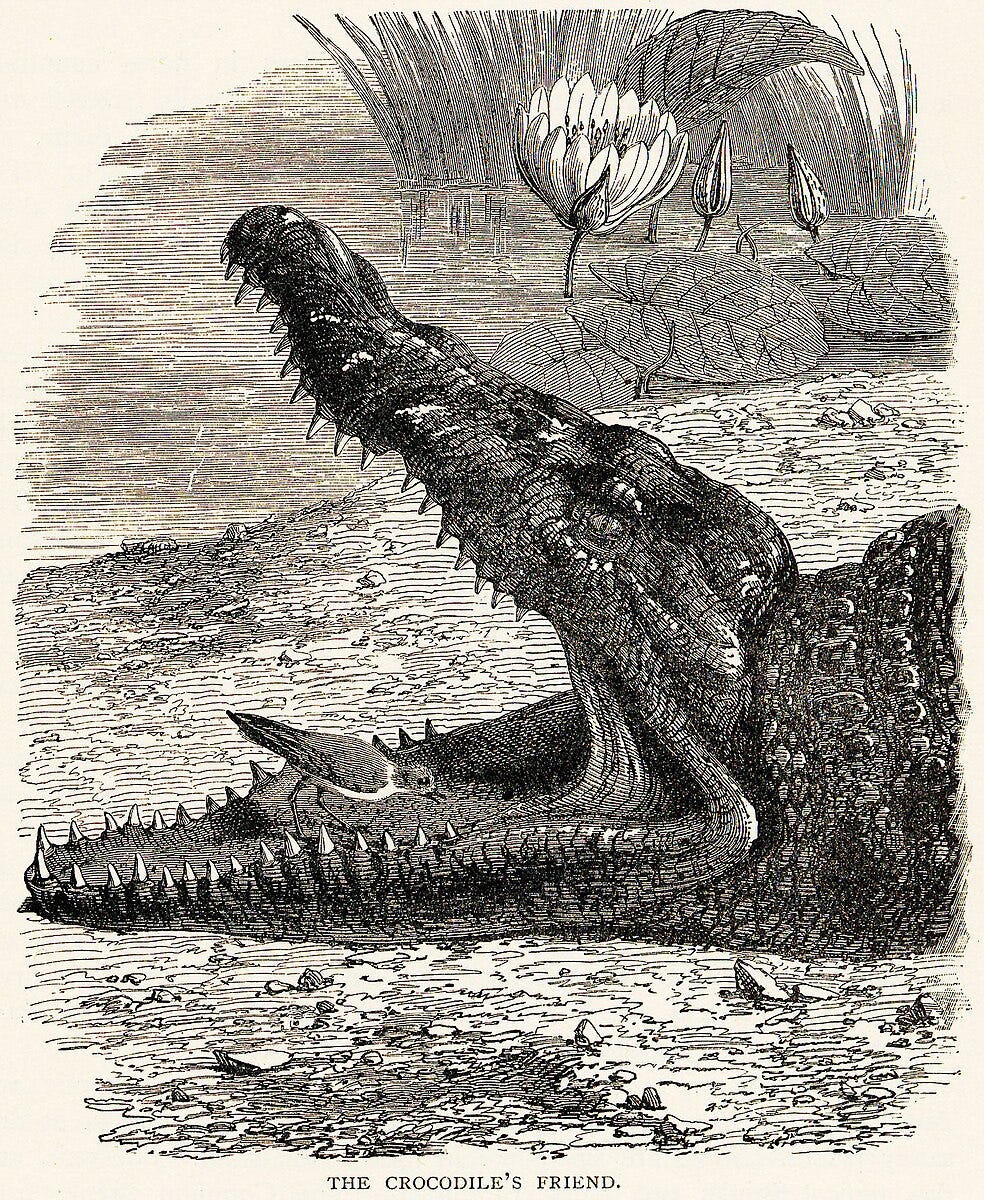

Cleaning partnerships have been a popular favorite for human observers dating back more than 2400 years to the Greek historian Herodotus. He reported accounts of Nile crocodiles gaping their mouths to allow a bird, probably the Egyptian plover, to climb inside and pick leeches off their gums. (Modern naturalists have struggled to observe this behavior.)

We like these partnerships, I think, partly because they challenge our gloomy view of nature as an endless round of ugliness and aggression, infamously “red in tooth and claw.” As scientists pay more attention, cooperative behaviors are beginning to seem at least as important as antagonistic ones in shaping the world around us.

Maybe we also take pleasure in the idea that so many of these partnerships are about grooming, a behavior that suits our own sanitary aspirations to shake off the dust and squalor of daily living. Or maybe we just identify: Once, in a remote village somewhere up the Amazon, I saw three small girls sitting in a row, legs astraddle, picking lice out of one another’s hair and eating their catch—as our own forebears did, probably more recently than we like to imagine.

Past scientists often treated reports of cooperation between species skeptically. Species that specialized in cleaning, one biologist wrote in 1987, were “nothing but very clever behavioral parasites.” But in recent decades the idea has gained ground that these partnerships are not just cooperative, or symbiotic, but often mutualistic, meaning that they leave both species in the partnership better off in terms of evolutionary fitness.

That doesn’t means such partnerships are simple, or sentimental. Feel-good interpretations of how they work almost inevitably miss the mark. The bluestreak cleaner wrasse, for instance, is a favorite model for mutualism studies. Along coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, this four-inch-long fish makes a living by setting up a cleaning station, usually alone or with a partner. It advertises its profession with a colorful streak down its flanks, like the pole in front of a barber shop, and it may sometimes do an awkward, lurching dance to drum up business. (Here’s a video.)

Its clients are a mix of smaller fish, generally nearby residents, and larger fish, which tend to roam more widely. The larger clients are big enough to snap up the wrasse for breakfast. But that’s not why they show up at a cleaning station.

Instead, they require ectoparasite removal and often assume a characteristic posture, fanning out their fins to invite inspection, as if to say, “Look what a mess I’ve become.” The wrasse then works its way along the client’s body and even into its gills and mouth picking off parasites and eating them. As it works, according to one recent study, it typically massages the client with its pelvic and pectoral fins, producing a calming effect. The relationship seems to add up to the provision of good food on one side and good service on the other. So, bingo, we have mutualism.

In 2003, however, after wrasses had been studied as a model of cooperative behavior for more than 40 years, University of Neuchâtel ecologist Redouan Bshary demonstrated that the wrasse isn’t really all that fond of eating parasites. It would far rather be nibbling the layer of mucus that protects its client’s skin.

If the client lurches like a barbershop customer who’s just gotten stuck with the scissors, that’s because the cleaner has given in to temptation. The massage may thus serve to relax the client enough for the wrasse to commit the transgression, and, with luck, to reconcile afterward for having done it. This behavior might seem to make the “very clever parasite” slander stick.

But client fish also know when they are getting a raw deal. So they may chase off cleaners that provide poor service and avoid them in the future. The wrasses also keep track, and cheat less often with a known client. This can’t be easy, as they manage 800 to 3000 cleaning engagements per day, according to Bshary. They cheat less with good clients, generally larger fish. They also cheat less, remarkably, when other prospective clients happen to be looking on. That suggests the cleaner is thinking about what others may be thinking. Researchers call that “theory of mind,” a trait they formerly ascribed chiefly to humans, not fish.

Bshary and Ronald Noë, his former doctoral adviser at the University of Strasbourg, describe all this as a biological marketplace in which the trade is shaped, much as in human markets, by factors like supply and demand, partner choice, and service quality. A partnership that’s mutualistic in one setting may turn exploitative or even predatory in another, then back to mutualist again.

Actual predators can also complicate business. For instance, the bluestriped fangblenny, a fish with a Yellow Submarine-worthy name, imitates the wrasse’s color, pattern, and dance. Once the unsuspecting client gets into position, these copycats skip the parasites and instead bite off chunks of the client’s scales and tissue. They also administer an opioid anesthetic that numbs the wounded client and causes its blood pressure to drop, making it easier for the culprit to flee the scene. The fangblenny is, in fact, a very clever parasite on the wrasse’s mutualism. But as in human swindles, its ruse works only if the dishonest fangblenny is a rare interloper among the more numerous, and more or less honest, wrasses.

The bottom line is that the old image of “nature red in tooth and claw” was not just wrong; it was also the most cynical and simple-minded lesson to take from the natural world. After Tennyson introduced the phrase in an anguished memorial poem for a friend, it passed into common usage and became a tool to justify brutal behavior in warfare and business, as in nature: If animals behave like that, why shouldn’t we?

But nature was always far more nuanced than that, with “give and take” at least as important as “eat or be eaten,” and plants and animals caught up, as we are, in what Martin Luther King Jr. once called “an inescapable network of mutuality.”

“Inescapable” was an interesting choice of words. Maybe, as we come to recognize how common mutualism is among other species, we can begin to accept it as a normal part of human nature, too—and stop trying so hard to escape. That doesn’t mean giving up on aggression, which is also part of our nature. It just means allowing cooperation to assume its rightful place as a saner model for living in the modern world.

Richard Conniff’s books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, The Atlantic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

love the reciprocity. we can learn something from the animals.

A better understanding of mutualism could lead to a complete reversal of economic systems such as capitalism which relies on scarcity and competition. Mutualism is a sharing economy found throughout the natural world from wrasses to root fungi.