Fool for Nature

A passionate interest in wild things was never just for the rich & privileged.

by Richard Conniff

It was May Day, International Workers Day, this week, and that spurred a memory of one of the everyday occasions when the ostensibly educated patronize and underestimate working people. I was writing the script for a documentary at one of the leading U.S. sources of natural history films—I forget whether it was the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, Turner Broadcasting, or some place else— and a senior producer gave me a script note. I rolled my eyes, the effect senior producers’ notes often have on almost anyone in earshot but especially writers. This one irks me even now: “When we make these shows, we need to keep the average Chicago bus driver in mind.”

He meant that we needed to dumb it down. I disagreed on two counts. First, viewers know when you’re talking down to them. Far better to bring them along on the journey. The BBC’s Natural History Unit, for instance, seemed to do well back then by understanding the intelligence and curiosity of its viewers, and occasionally even introducing an ecological concept that might require a certain amount of thought.

The second disagreement was the killer for me: This senior producer, whose grand ambition in life reached no higher than to become that mighty panjandrum, the EXECUTIVE producer, assumed that the average Chicago bus driver was by definition a dolt. My experience was that people in seemingly dull jobs often cultivate a passionate interest in topics entirely unrelated to their work. This is my very roundabout way of introducing one such character, from the eccentric world of nineteenth-century natural history:

THOMAS EDWARD, a shoemaker in Banff, on the northeast coast of Scotland, had been afflicted with the love of “beasts” from earliest childhood and on that account managed the singular achievement of getting expelled from three schools before he finally abandoned formal education at the advanced age of six. His infractions included applying a horse leech to the leg of a fellow student and smuggling a jackdaw into class, hidden in his trousers. A jackdaw is a very large bird for a small boy to hide in his trousers, but Edward was not easily discouraged. This predilection continued into his working life, when he angered a boss by bringing moles to work and alarmed a fellow worker with runaway caterpillars.

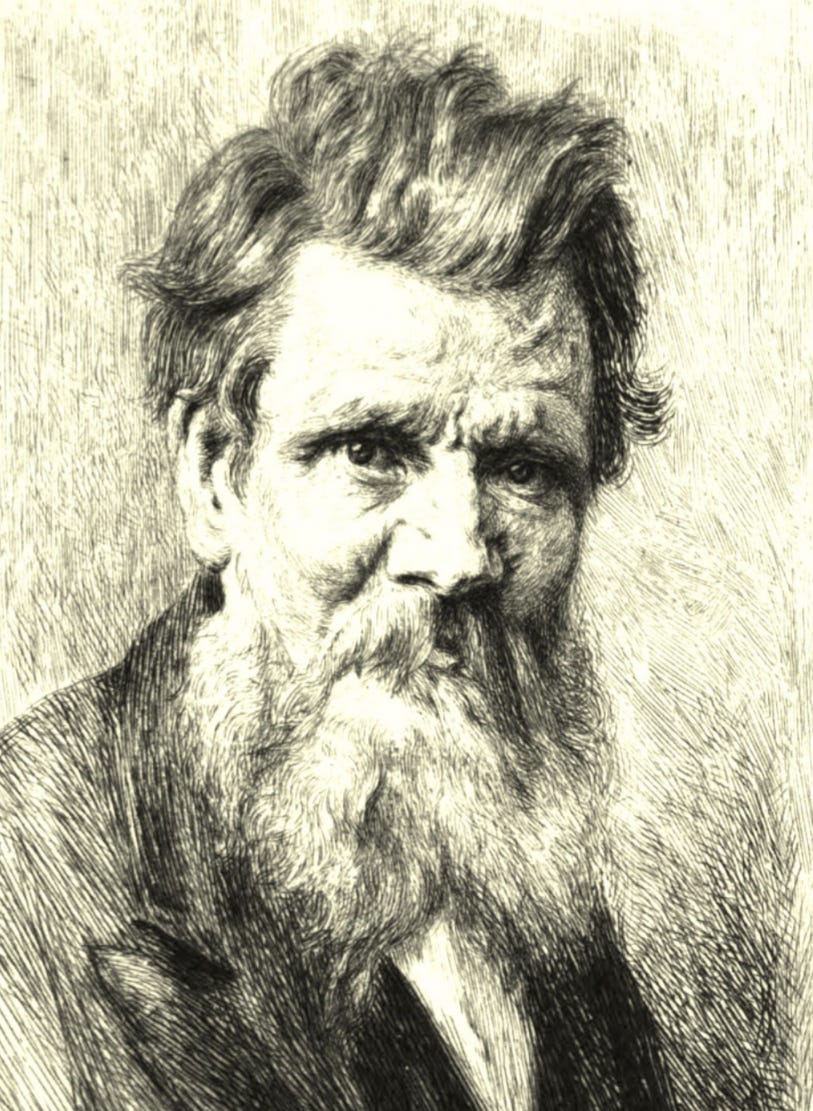

As an adult, Edward was a fierce-looking character, with deep-set eyes, a high brow, hair that rolled back in a windswept wave, and a ragged beard. His work in a shoe factory consumed the hours from 6 a.m. to 8 or 9 p.m. six days a week. Sundays, like his devout Scottish neighbors, he spent in prayer and at rest. But at night he wandered the north coast countryside collecting almost anything that lived. He carried boxes for butterflies and beetles, a book for pressing botanical specimens, and a decrepit shotgun, its barrel lashed to the stock with heavy twine.

When he got tired, he often bedded down in the shelter of rocks, graveyards, or abandoned buildings. Sometimes he tucked himself feet first into a fox hole or badger hole in a sandy bank. Once, a badger came home and, finding him there, bared its teeth. With regret, Edward shot it. (He did not like wasting ammunition). Another night in a rainstorm, he slept under a flat gravestone supported by four pillars. At the height of the storm, a weird moaning awakened him--not ghosts, but as he discovered when they raced across his legs, just a couple of cats.

Edward’s zeal for the natural world ran even deeper than this might suggest. Whatever he killed, he wrapped in gun wadding and slept with it stored atop his head, under his hat. One morning he woke with “something cold pressing in betwixt my forehead and the edge of my hat.” It was a nose, with a live weasel attached, hoping to get at some birds he had stored there. Twice, Edward grabbed the weasel and tossed him aside, and then went back to sleep. The third time, he got up and walked to a different field 100 yards away. The weasel followed him and on the fifth attempt, Edward wrote, “I suffered him to go on with his operations until I found my hat about to roll off. I then throttled, and eventually strangled, the audacious little creature, though my hand was again bitten severely.”

Then he went back to sleep, with this new specimen no doubt safely stashed in the overhead compartment. The same thing happened on other occasions with rats and even a polecat, with which he wrestled for two hours. “I never wasted my powder and shot upon anything that I could take with my hands,” he declared.

This makes Edward sound like some kind of backwoods sociopath, and he may have seemed that way to unfortunate strangers who happened to see him lurch up from among the gravestones just before dawn. But in fact he was a learned naturalist, elected by the Linnean Society to its small circle of associates.

He was also a family man. His biographer, the self-help author Samuel Smiles, dryly noted that “he knew nothing about ‘Malthus on Population’” but “merely followed his natural instincts.” His wife Sophia “was bright and cheerful, and was always ready to welcome him from his wanderings.” Thus they managed to produce eleven children together and spent much of their lives on the brink of starvation. (Impressively, in that era before antibiotics or modern vaccines, all of them were still alive when Edward died at age 72.)

Other naturalists who beseeched him for specimens mostly seem to have been oblivious to his circumstances, though one benefactor supplied him with a microscope for his work. They often promised to send the books he requested, but seldom delivered.

At one desperate point, after an exhibition of the specimens he had collected around Banff failed to earn the money he needed to feed his family, Edward attempted suicide. But as he waded into the sea to drown himself, the sight of a rare bird distracted him. He spent the next half hour chasing it and must have realized that he was too attached to life in all its splendid permutations to give up so easily.

Back home, he went on supplying crustaceans to Mr. Bate, echinoderms to Mr. Norman, sponges to Mr. Bowerbank, sea squirts and mollusks to Mr. Alder of Newcastle, and so on. What Edward mainly got from them were the scientist names of the specimens he supplied and the chance to correspond with like-minded scientists. He also enjoyed the honor of having an isopod named for him, Praniza edwardii, and a fish, Couchia edwardii. But since both proved to be synonyms for previously described species, the names later vanished.

One book, A History of the British Sessile-Eyed Crustacea, praised him as “that indefatigable lover of nature“ and cited him as the source for 20 new species in that group alone. Otherwise, Edward, like many collectors of that era, worked purely for the love of the natural world.

As he put it, “I have been a fool to nature all my life.”

##

Or not necessarily such a fool. In 1877, on the recommendation of Charles Darwin among others, Queen Victoria singled out Thomas Edward for special honor, with a civil list pension. Today, the house where he lived bears Britain’s real mark of honor, a blue medallion identifying it as the home of “Thomas Edward, the Banff Naturalist.” The work he did remains a valued resource for other friends (and fools) of nature to this day.

I first encountered Thomas Edward while researching my book The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton). Outside magazine praised it as "an anecdotal romp through the strange history of naturalism. Absurd characters, exciting discoveries, and fierce rivalries abound," and BBC Focus called it "A swashbuckling romp…brilliantly evokes that just-before Darwin era."

Other Reading and Viewing:

Smiles, Samuel (1876) The Life of a Scotch Naturalist.

Secord A. “Be what you would seem to be”: Samuel Smiles, Thomas Edward, and the Making of a Working-Class Scientific Hero. Science in Context. 2003;16(1-2):147-173.

And for eye-rolling comments and behavior by entertainment executives, I highly recommend “The Studio,” starring Seth Rogen, on Apple+, especially the first two episodes.

I have a copy on my shelf

Great story.