Fossils, Bison, & American Indians

How an 1870 expedition gave rise to the conservation movement

by Richard Conniff

The American conservation movement got started, according to the standard history, when sport hunters in the late nineteenth century became alarmed by the rapid disappearance of game animals. But the real start happened decades earlier, in the summer of 1870, when an expedition into the American West brought an unpromising young college graduate face to face with the fossils of extinct species and with living American Indians.

George Bird Grinnell seems to have joined the expedition, led by Yale paleontologist O. C. Marsh, on a lark. Fossils “meant nothing to us,” he wrote, of himself and his fellow student-explorers, who were distinguished mainly by their parents’ ability to pay for the trip. He wanted only “to shoot buffalo and to fight Indians.”

Grinnell had grown up in upper Manhattan, the son of a stockbroker. He’d been a mediocre student, interested mainly in the natural world around the family home. His father pushed him to apply to Yale College, as ambitious and well-to-do parents still do today. With the help of expert tutoring, Grinnell squeaked through the entrance exam. After that, he skittered along on the academic fringes, getting suspended at one point for a prank and graduating in a dead heat for second-to-last in his class.

His subsequent expedition with Marsh made all the difference. Grinnell got hooked at first by the hunting, the open country, and encounters with colorful western characters. But something also seemed to shift in him as he dug out the fossil remains of extinct crocodiles, turtles, and early mammals. He was seeing and touching the evidence that any species, and whole worlds of species, had become extinct.

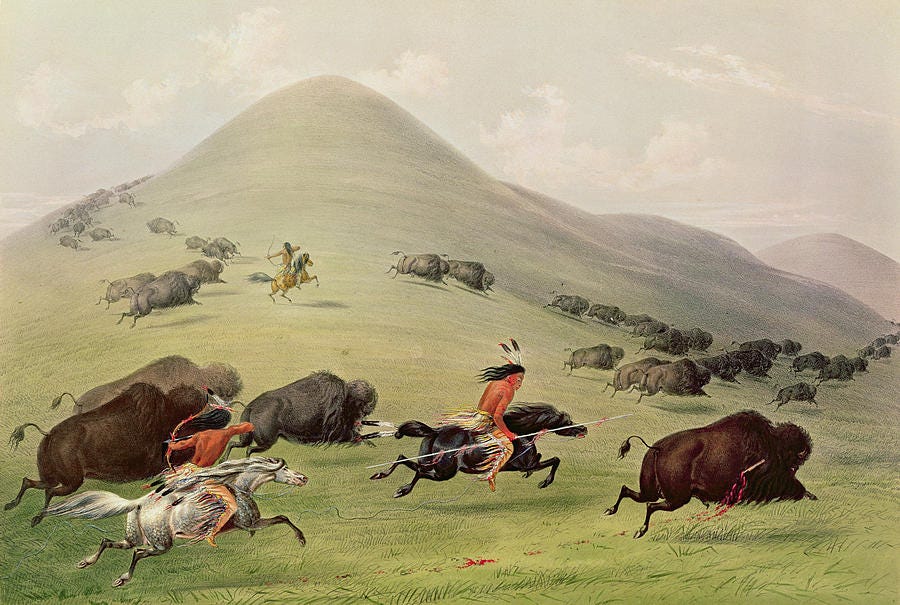

The other great revelation for Grinnell was the experience of coming to know two Pawnee guides as hunting companions and friends. When the expedition ended, Grinnell reluctantly joined the family brokerage. But in the summer 1872, he went west again to northern Kansas, to take part in a traditional Pawnee buffalo hunt with a party of 800 braves, who rode amid charging buffalo firing arrows repeatedly from horseback. The hunt, as Grinnell recalled it, was a display of tactical skill and discipline, geared to take only as many animals as needed.

It would turn out to be that tribe’s last great buffalo hunt. By the end of 1873, newcomers with a very different attitude had eradicated the buffalo from Kansas. It was the same in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming, where Grinnell traveled in the summer of 1874. He did not see a single living buffalo, he wrote, in a country that had been a “favorite feeding-ground” only a few years before. Now “their white skulls dot the prairie in all directions.”

He had begun to write for a new weekly called Forest and Stream, where he drew a pointed contrast between the appallingly wasteful slaughter of buffalo by white hunters and the Indian hunter’s economical practice of using almost every scrap of what he killed. He called for federal action to stop the senseless killing.

By then, Grinnell had given up on Wall Street and become a graduate student and unpaid assistant to Marsh at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. Crates continually arrived there from other western expeditions and from private fossil hunters. Prying open these crates, Grinnell found astonishing creatures that were not just gone, but embedded in stone, as if they had never lived. Any species on Earth, it seemed, could become extinct.

An 1875 expedition took him to Yellowstone, which the federal government had designated in 1872 as the world’s first national park--but without enforcement. Grinnell found whiskey dealers and poachers camped out in the middle of the park, openly butchering the supposedly protected wildlife.

“Buffalo, elk, mule-deer, and antelope are being slaughtered by thousands each year, without regard to age or sex, and at all seasons,” he wrote. “Of the vast majority of animals killed, the hide only is taken,” with the rest left to rot, or be scavenged by wolves. “Females of all these species are as eagerly pursued in the spring, when just about to bring forth their young, as at any other time.” This scene of “wholesale and short-sighted slaughter” would haunt Grinnell for the rest of his life, and drive him to campaign relentlessly for some of the most important wildlife protection laws in American history.

Grinnell was soon contributing a weekly column to Forest and Stream, while also helping produce Marsh’s first great paleontological monograph, on a group of extinct toothed birds first discovered on their 1870 expedition. He was also successfully pursuing his doctorate, with a thesis on the greater roadrunner. It was a small lesson in the hidden potential of unpromising students. But the workload drove Grinnell to headaches and insomnia. A doctor urged him to cut back, and in 1880, Grinnell left Yale to become editor-in-chief of Forest and Stream, in which he and his father had bought up a controlling interest.

There he foresaw the decline of the American West as if in a vision: Mines would ravage the landscape, and “a thousand smelting furnaces” would blacken “the pure, thin air of the mountains.” The game animals, “once so plentiful, will have disappeared with the Indian … All arable land will be taken up and cultivated, and finally the mountains will be stripped of their timbers and will become simply bald and rocky hills.”

For the next twenty years, he worked to forestall this fate, focusing first on laws to protect Yellowstone National Park. He fought down a bid by a group calling itself the Yellowstone Park Improvement Company to grab a one-square-mile monopoly around each of the park’s major attractions, with an unlimited right to cut timber, at an annual rent of $2 an acre. Grinnell wrote editorials, and also traveled to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congressmen, “the meanest work I ever did.”

In 1893, after two decades of “struggle and sweat and fight,” Grinnell and his allies defeated a plan to run a railroad through the park. The following winter, Grinnell sent a reporter to Yellowstone to write about the status of the plains buffalo, by then eradicated from all of North America, except for a small herd hiding out in the park’s Pelican Valley. Scarcity only made them a more profitable target for poachers.

Shortly before Grinnell’s reporter arrived, the park superintendent paid out of his own pocket to send out a two-man anti-poaching patrol on skis. In mid-March, the patrol spotted tracks in the snow and followed them into Pelican Valley itself. There, they spotted the notorious poacher Edgar Howell skinning one of five buffalo he had just killed, among the last of their kind.

The lead scout, Felix Burgess, managed to ski down across hundreds of yards of open country, leap a 10-foot-wide ditch, and arrive undetected between Howell and his rifle. “I called to him to throw up his hands,” Burgess told Grinnell’s reporter, “and that was the first he knew of any one but him being anywhere in that country. He kind of stopped and stood stupid like, and I told him to drop his knife.”.

Forest and Stream turned the arrest into a national scandal. Grinnell had cultivated powerful allies over the years, among them a New York assemblyman named Theodore Roosevelt. Together, he and Roosevelt had co-founded the Boone and Crockett Club, an organization of wealthy and well-connected Eastern big game hunters dedicated to the passage and enforcement of laws protecting wildlife. Now these forces came together around the man Roosevelt described as that “infernal scoundrel” Edgar Howell.

The park superintendent had no power to do more than escort Howell out of the park and admonish him not to come back. But within a week of the arrest, John F. Lacey, a Republican Congressman from Iowa, introduced a bill to outlaw the taking of wildlife in Yellowstone National Park, with a jail term of up to two years for each offense. Congress soon passed the law and later extended it to protect other national parks.

It was the salvation of an American icon. The park’s plains buffalo—the last remnant of the 30 million or so that had roamed across North America at the start of the nineteenth century--continued to decline for a few more years, to a low of just 23 individuals at the start of the twentieth century, about as close to extinction as a species can come without passing over into oblivion. But from there the species slowly recovered, to a population today of 4900 purebred buffalo within Yellowstone itself, more than 20,000 in North America, and another 500,000 that are cross-bred with domestic cattle.

Through Forest and Stream, Grinnell also took on the fashionable practice of wearing feathers--and even whole birds and nests--as ornaments on women’s hats. He thought legislation could do little to stop “this barbarous practice.” So he pushed for a change in public opinion “inaugurated by women.” The women he hired to write for a new magazine, which he called Audubon, came to the task with talons out. The poet Celia Thaxter, for instance, wrote of one fashionable lady dressed in “a charnel house of beaks and claws and bones and feathers and glass eyes upon her fatuous head.” By reaching out to women, Grinnell “played a central role,” according to one historian, “in bridging the gender gap” in the developing conservation movement.

In 1894, Forest and Stream proposed a ban on all commercialized killing of wildlife. Rep. Lacey responded with a broad new law to limit trafficking in plants and animals nationwide. More than a century later, the Lacey Act remains the nation’s fundamental law for the protection of wildlife. Grinnell was also a major influence on the Migratory Bird Treaty with Great Britain in 1916, which currently protects about 800 bird species, and on the passage of conservation-based hunting laws in many states.

Some recent historians now criticize Grinnell and his Boone and Crockett allies as a wealthy Eastern elite, imposing their will on distant landscapes, at the expense of local people, who were often working class or subsistence hunters. The language in Forest and Stream was often tainted with class and ethnic overtones. The term “pothunter,” one scholar writes, became a euphemism for immigrant hunter, and “the most reviled were the Italians.” As new national parks began to spring up elsewhere, the new style of “fortress conservation” at Yellowstone would become the model for extirpating and excluding indigenous communities from protected areas around the world.

Some Boone and Crockett members, though not Grinnell, were also leading figures in the growing anti-black, anti-immigrant eugenicist movement. The damage they did is a subject for another story. But my great-grandfather was one of those Italian pothunters, on the northern fringes of New York City. Early in the twentieth century, he and his family were among those forced to relocate by a highway project one of the Boone and Crockett eugenicists designed in part to eliminate pockets of “undesirable” groups.

Even so, the alternative to Grinnell’s brand of conservation at the time would have meant leaving Edgar Howell to his bloody work in Pelican Valley and allowing the buffalo to precede the passenger pigeon in its unbelievably sudden rush from ubiquity to extinction. We would have no Glacier National Park or Adirondack Forest Preserve, both largely Grinnell’s doing.

Moreover, in books about the Pawnee, the Cheyenne, and the Blackfoot tribes, “Grinnell, as much as any man of his generation, worked diligently to commit Indian memories to the page and thus preserve them,” historian Sherry Lynn Smith wrote, in her 2000 book Reimagining Indians. He recounted Native American “words, actions, practices, history, and religious beliefs as objectively, accurately, and faithfully as possible.” As a result, “Grinnell’s writings helped lay the foundation for a fundamental reassessment of Indians and thus contributed to an evolving perception of them as people worthy of interest and respect …”

When Grinnell died, age 88, on the brink of World War II, The New York Times called him “the father of American conservation.” It was an extraordinary transformation from the fecklessness of his privileged youth. Would it happened if he had never gone on O.C. Marsh’s Expedition of 1870?

I doubt it. As he listened to the voices of fossil species exhumed from their graves on that expedition, and of American Indians in the last days of their unfettered freedom, George Bird Grinnell rose into his potential. He used his newfound power to launch a movement that today remains our best hope for saving what’s left of the natural world.

Richard Conniff’s books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

Wow! Amazing story… I was unaware of Grinnell and his early efforts. Thanks for educating me.

Avarice unleashed and a Yale man’s call to arms! A ripping yarn, in word and deed, this bracing essay will restore your faith in moral fiber.