Hearing the Ghost of Madison Grant (Part 1)

And that's not his conservationist voice doing the talking.

by Richard Conniff

I used to tune out when my father was going on about eminent domain: How his immigrant grandparents had built up a modest little homestead, with two houses, three grown children, and a flock of chickens on the banks of the Bronx River, in northernmost New York City. And then, around 1913, how the government seized the property to make way for the Bronx River Parkway. That the episode still rankled after almost a century just seemed like a manifestation of my father’s cranky late life conservatism.

That was before I found out about Madison Grant, though.

It’s a name you should bear mind this year, as we deal with a presidential candidate, Donald Trump, who has promised, if elected, that he will round up undocumented immigrants, build camps to forcibly detain them, and carry out the “largest domestic deportation operation in American history.” Indeed, if the Supreme Court accepts Trump’s argument that a former president, “enjoys absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for his official acts,” there is really no limit to what he might feel entitled to do, on the immigrant issue or anything else.

So what’s the link to Madison Grant? It may seem at first like a stretch, because Madison Grant at least did some good in his life. The National Park Service was in large part a product of Grant’s work as “the greatest conservationist that ever lived,” according to one early Park Service director, and as the creator of “the park concept,” in the words of another. But conservationists rarely even whisper his name these days because his peculiar line of thinking also helped lay the groundwork for the death camps of Nazi Germany.

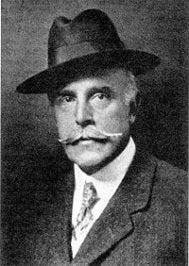

Born in 1865, Grant enjoyed a blueblood Manhattan childhood thanks to his mother’s wealth, and his father’s reputation as a doctor and Civil War hero. At 16, he went for four years of private tutoring in Dresden, Germany, before moving on to Yale College and Columbia Law School.

He was a handsome, urbane figure with a thick mustache, steady, deep-set eyes, and a reputation as a ladies’ man. He set up a Manhattan law office but rarely practiced. Nor did he ever hold public office, despite his keen political interests. Big game hunting was his real passion, according to the definitive 2008 biography Defending the Master Race, by historian Jonathan Spiro, and he recognized early on that reckless overhunting was driving many species to extinction. It became his first great cause, often in collaboration with Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, George Bird Grinnell and like-minded hunters in a spectacularly influential little group that called itself the Boone and Crockett Club.

By 1895, Grant had founded the committee that drove through construction of the Bronx Zoo, dedicated to the preservation of North American species. He also founded the Wildlife Conservation Society, now among the most effective such organizations in the world. Among his many other initiatives, Grant effectively ended the commercial sale of wild game in the United States, launched the campaign to stop the last of California’s magnificent redwoods from being logged, worked to save the American bison from extinction (restocking the Plains with bison from his zoo), and pushed for the creation of Glacier, Denali, Olympic, and Everglades national parks. It would be a monumental legacy for anyone.

The big, ugly problem was that Grant soon began extending his efforts on behalf of North America’s native species to what he considered its “native American” people—not Indian tribes but Northern Europeans, preferably “of Colonial descent.” He published his book The Passing of the Great Race in 1916 to call attention to the plight of the “Nordics,” a new word he popularized. “Unlimited immigration” and intermarriage, he warned, were “sweeping the nation toward a racial abyss.”

The book was a 476-page pseudoscientific compendium of stereotypes. Black men were “a valuable element in the community” so long as they remained “willing followers who ask only to obey and to further the ideals and wishes of the master race.” The Irish tended to be “intellectually inferior” and “gorilla-like” in appearance, and “the Slovak, the Italian, the Syrian and the Jew,” were “social discards.” He worried that “the sweepings” of Europe’s jails and asylums were adopting “the language of the native American,” wearing his clothes, stealing his name, and “beginning to take his women.” Grant was especially enraged at “being literally driven off the streets of New York City by the swarms of Polish Jews.”