by Richard Conniff

Animals have been hitching a ride on other animals almost as long as there have been other animals to hitch a ride on. Researchers working on the border of Austria and Italy recently discovered fossils of marine invertebrates that appear to have been riding piggyback on other species 425 million years ago. The riders were juvenile crinoids, better known as “sea lilies” for their branchy, undulating arms. Modern crinoids use star-shaped attachments called “holdfasts” to cling to the sea floor. But the concave shape of the holdfasts left behind by these ancient juvenile crinoids indicates instead that they latched onto drifting algae, or onto the shell of some nautilus-like creature, the better to get as far away from home as possible before settling down. It’s a clue, according to Ohio State University researcher William Ausich, to how certain crinoids achieved a global distribution “that defies all logic.”

Likewise, European researchers recently found a mite riding on the back of a spider, both perfectly preserved in amber—that is, fossilized tree resin--from the Baltic region. The mite was almost too small to see with the naked eye. But with the help of high-tech scanning devices, the researchers were able to examine it in detail and date the find to at least 50 million years ago.

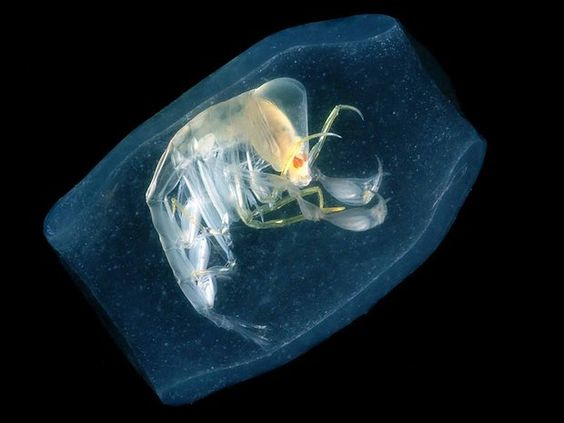

One small problem in talking about animal hitchhikers is that roughly 40 to 50 percent of all species on the planet are parasites. That means they spend their lives hitching a ride on some other species. But their motive is generally to suck out their host’s precious bodily fluids, a violation of hitchhiking etiquette. For instance, a small crustacean called Phronima hijacks the gelatinous bodies of salps, siphonophores, and other marine species to make a barrel-like, translucent house in which to raise its young. One scientist’s account of this interaction begins: “The female entered the salp, cut out the brain and gillbar, and consumed them …” Better to leave the rest to your imagination. But the image of mama Phronima drifting within her glassy new home, her amber eyes glowing like coals in her outsize head, gives credibility to reports that this was the model for the belly-bursting monster in the movie Alien.

Freshwater mussels also begin their lives as hitchhikers (and parasites) on other species. The North American genus Lampsilis, for instance, is an unspectacular creature, until it opens its shell and sticks out a fleshy protrusion that brilliantly mimics a small, wriggling fish. It’s a fishing lure, evolved for the purpose of attracting a local bass, walleye, or perch.

When the fish bites, the fleshy protrusion breaks open like a piñata, releasing a dense cloud of mussel larvae. They clamp onto the would-be predator’s scales and gills, turning it into their nursery and minivan for weeks or months of development. The larvae actually become embedded in their host’s flesh, until they mature enough to break out and settle in a new home.

“You talk about the ‘blind watchmaker’ model of evolution,” says Michael Gangloff, a conservation biologist at Appalachian State University. “Here you have this animal that has no head,” much less eyes, to see either the fish they are mimicking or the one they are trying to attract. And yet, “using a limited evolutionary toolkit, they have come up with some pretty amazing tools for attracting fish.”

Some mussels, says Gangloff, are less subtle than Lampsila. They use an insect-like lure to attract darters, then grab the fish by the snout and pump it full of larvae before letting it go. Some other mussel species target sea-going fish returning to their breeding ground, and their larvae catch a ride upstream to distant parts no mussel could ever reach on its own power.

In the natural world, much as on the highway, it can be hard to separate the friendly hitchhikers from the troublemakers. For instance, we tend to celebrate the colorful birds called oxpeckers for picking off ticks as they ride along on zebras, rhinos, giraffes, and almost any other large mammal in the African bush. But researchers now say these birds also pick open wounds to drink the blood of their host animals. (Cattle egrets, on the other hand, appear to be well-behaved travel companions.) Copepods and other small crustaceans often pass their lives innocently lounging about on a jellyfish or other gelatinous marine creature. “But if the food runs short, they might eat up the host as well,” says Larry Madin of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Even honest hitchhikers can inadvertently do damage. For instance, off the coast of British Columbia and Washington, the larval stage of the coldwater shrimp Pandalus danae likes to ride atop a small jellyfish. It is, in theory, surfing for its dinner: All it has to do is hang on, open its mouth, and inhale the passing zooplankton. But the excess expenditure of energy sometimes kills the jellyfish.

Sorry to say, the ambiguity of the hitchhiking experience applies to humans, too, and not just for the animals we ride, but for the ones that ride us: Follicle mites are sausage-shaped little spider relatives, each about a sixtieth of an inch long. They pass their lives head-down in our hair follicles, mostly concentrated around the brow and other parts of the face. They dine on dead skin cells and the oily products of the sebaceous glands, and scientists long regarded them as harmless fellow travelers. But they now consider them parasites, for their occasional role in certain skin disorders. Don’t worry about it, though. There is nothing we can do to be rid of them.

(To Be Continued Tomorrow)