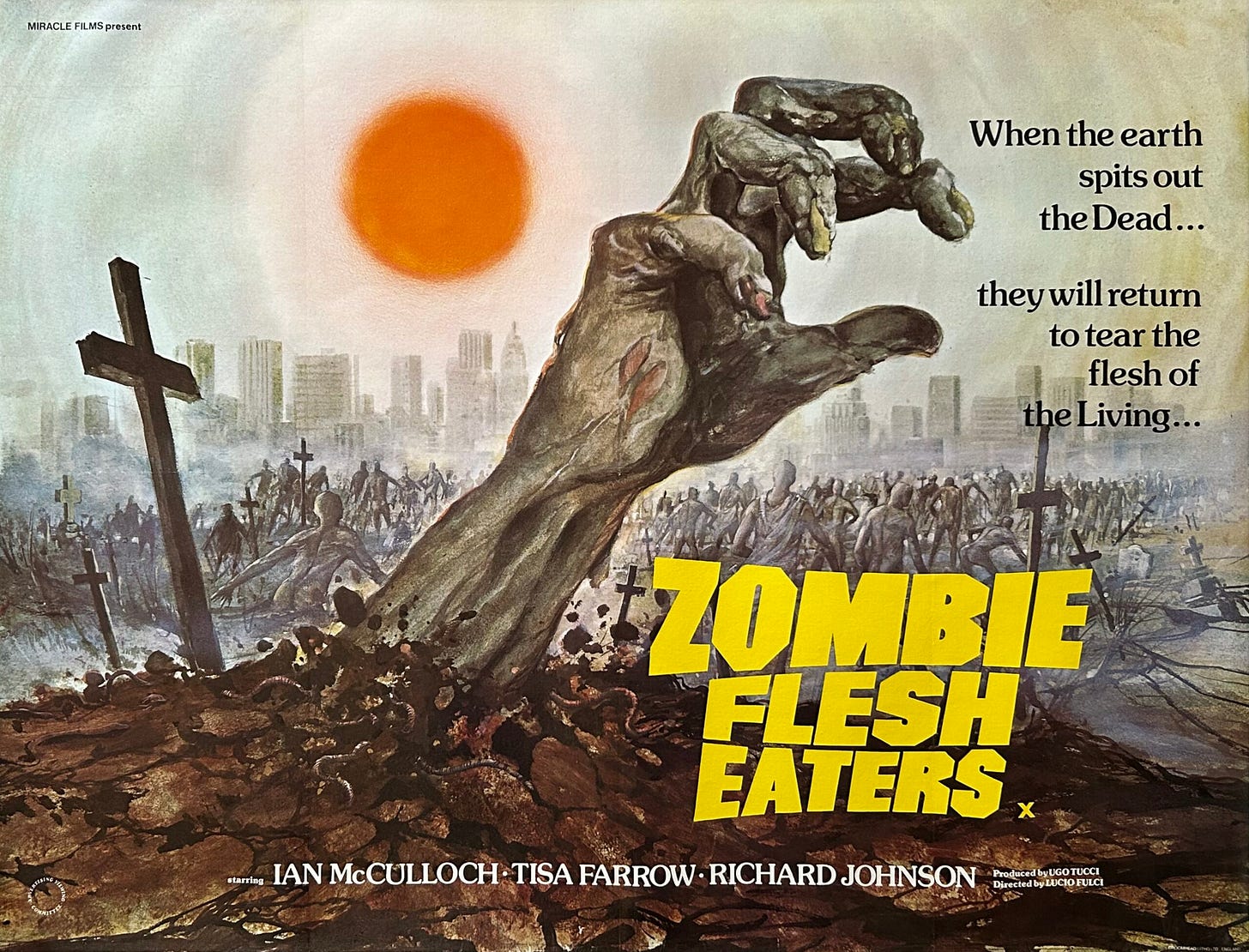

Is Trump Setting up a Flesh-Eating Fiesta?

Federal workers drove out a hideous livestock parasite. Firings could bring it back.

by Richard Conniff

This is a story about why federal workers matter. It’s also a story about a notorious pest, and the federal workers who defeated it. And it’s about politicians who think trashing federal workers is a good way to make headlines and get votes, without regard for the kind of nightmarish consequences than can result. Yes, I’m thinking of Donald Trump’s campaign assessment of federal workers: “They're crooked people. They're dishonest people. They're going to be held accountable.” And I’m thinking of Elon Musk’s mindless mass firings, and the nightmarish consequences that are likely to result as early as this year.

The pest I have in mind is the screwworm fly, which can be even more loathsome than its name suggests. The female lays up to 300 eggs at a time in open wounds. For instance, she’ll target the navel of newborn mammals, including calves, wildlife, and sometimes humans. Eyes, nose, mouth, and other soft, damp tissue is the ideal habitat for the larvae, or maggots, which soon emerge from the eggs.

These maggots eat the flesh of their host, burrowing (or screwing) down and leaving a hole the size of your fist by the time they are ready to drop off to the ground and on to their next stage in becoming flies. Enough flies—and aren’t there always enough flies?—and their maggots can kill a full-grown steer in under two weeks.

Edward F. Knipling (1909-2000) encountered this nasty specimen growing up in southeastern Texas. His father put him to work early on doctoring screwworm-infested calves on the family farm. Studying their behavior, and that of other problem insects, led “Knip” to become an entomologist. The U.S. Department of Agriculture gave him a job specializing in screwworms, which were causing huge economic damage to the cattle industry—and certainly doing equal damage to wildlife. The work involved long days observing screwworms on rabbit carcasses and the behavior of adult flies in a facility named “the stinkhouse.”

Let’s pause for a moment and try to imagine “crooked people, dishonest people” choosing to make a career this way. Imagine Donald Trump, for instance, spending years studying insects, amid the smell of death, unpraised, hardly even noticed, and like Knipling, supporting his wife and five children on a government worker’s salary. Imagine Trump motivated not by visions of gold-plated toilets and other such gewgaws but by a genuine concern for the public good. No? I can’t see it either.

Using tax dollars for what developed into a study of the sex lives of screwworms made Knipling and his USDA colleague R.C. Bushland a natural target for political and even scientific ridicule. Like a lot of basic research, their work yielded insights but for many years no practical results. According to Knipling’s biographers:

Observing that male flies mated repeatedly while female flies mated only once in their lifetime, Knip believed they had found a weak link in the screwworm’s life cycle that might be exploited for control. The question was: “How?”

World War II diverted Knipling to the business of protecting U.S. troops from mosquitoes, lice, and other harmful insects. But he continued to puzzle over the weakness in screwworm fly mating behavior until:

With imagination and innovation he conceived the idea of using sterile insects for population suppression and eradication. He reasoned that if male flies could be produced in large numbers, sterilized, and released into the environment they might out-compete, on a simple probability basis, the wild fertile males in breeding with females. Because female screwworms mate only once, those that were bred with sterile males would lay infertile eggs and thus not produce any progeny.

This was a wildly improbable notion on two counts: No means of mass-sterilizing insects existed at that time. And the screwworm fly occupied a vast home range, from Argentina up through South and Central America and from southern California across to Florida. When Knipling shared his idea with fellow scientists, according to one account, “the responses ranged from intense skepticism to outright laughter. ‘You just can’t castrate enough flies,’” they replied, as if Knip and Bushland were going to go after the flies with microscopic snippers. “And this was where their idea rested for over a decade.”

Two developments put Knipling’s idea in reach: Another researcher devised a way to sterilize fruit flies using x-rays. The USDA would not fund an x-ray machine to replicate this research in screwworm flies. But by smuggling the flesh-eating insects into a nearby Army hospital’s x-ray facility during off-hours, Bushland demonstrated that sterilization worked equally well in screwworm flies without otherwise impairing their behavior. Under Knipling’s direction, he also developed a factory-like method for mass producing screwworm flies.

IN 1954, two decades after Knipling began his research, the Dutch government turned to the USDA for help with a screwworm infestation on the Caribbean island of Curacao. The two researchers had the chance to test the sterile-insect technique in the real world. They shipped 170,000 sterilized flies a week from a laboratory in Florida, and in just seven weeks eradicated the species from Curacao. That demonstration of the method led to eradication of screwworm flies from the U.S. Southeast by 1959, and the entire United States by 1966. Eradication followed in Mexico and southward, creating a protected area down to the Darien Gap, on Panama’s border with Colombia.

Knipling and Bushland won plenty of scientific honors for their work. But their success still did not spare them from ridicule by politicians of both major parties. In 1975, notably, U.S. Sen. William Proxmire, the otherwise progressive Democrat from Wisconsin, thought spending tax dollars to study “the sex life of parasitic screwworm flies” would generate the desired mix of outrage and laughter. He handed Knipling one of his first headline-making “Golden Fleece” Awards. And in fact, the research and application of the sterile-insect technique would cost taxpayers an estimated billion dollars over 50 years. Serious money.

But Proxmire was completely ignoring the benefit side of cost-benefit analysis—a a deeply dishonest tactic that Trump 1.0 tried to turn into official policy. The USDA later estimated those benefits for the larger economy at $2.8 billion—or $5.7 billion, in today’s money—per year. Other researchers have since extended the sterile-insect technique to control fruit flies, another important agricultural pest, and tsetse flies, the main carrier of sleeping sickness. They have also deployed the technique experimentally to limit the spread of mosquito-borne diseases including malaria, yellow fever, and Zika virus. Sterilized-insect production facilities now operate in 25 countries. Like a lot of the work performed by federal workers, screwworm fly research has yielded an enviable return on the original investment.

So what’s the potential nightmare? Over the past three years, the screwworm fly has been mounting a comeback. As of last October, Panama had more than 18,000 cases in animals—and 79 in humans. Mexico has reported 1000 cases in animals, with incidence moving northward toward the U.S. border. The resurgence has been variously attributed to a decline in cattle inspections by Central American countries, increased illegal shipping of cattle, U.S. government spending reductions, and tensions on Mexico’s border with the United States.

In February, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Inspection Service (APHIS) announced that it will begin flights to release sterilized screwworm flies across affected parts of Mexico—effectively moving the buffer zone hundreds of miles closer to the U.S. border. The two nations also recently signed an emergency agreement to cooperate on containing the threat.

Will it be enough? That depends on Trump 2.0. This is the same administration that:

fired federal nuclear safety experts, and then, having deleted their work emails, could not immediately locate them for re-hiring.

put billionaire Elon Musk in position to fire federal bird flu experts as that outbreak was spilling over to humans.

allowed Musk to destroy the U.S. Agency for International Development, in full knowledge that this would lead to millions of deaths, mostly of children.

And, as Musk gleefully admitted, “accidentally canceled” Ebola prevention in the middle of an emergency deployment to contain an Ebola outbreak in East Africa.

The USDA has also been subject to mass firings of thousands of workers—including APHIS entomologists and agricultural inspectors. It’s unclear whether those firings have targeted screwworm fly research programs at the Knipling-Bushland U.S. Livestock Insects Research Laboratory in Texas and Panama. A former staffer there, who asked not to be named, described the laboratory as “pretty hush-hush” in ordinary times, and currently operating under a Trump Administration gag order. (The laboratory did not respond to a request for comment.) He also worried that Trump would ignore the problem because, “Oh, it’s just Mexico. Why are we worried about it?”

Perhaps prudently, Texas is not expecting the federal government to stop a screwworm fly invasion. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department recently asked residents to monitor wildlife, livestock, and pets for head shaking, the smell of decaying fish, the presence of maggots, and a tendency to isolate from other animals or people—all symptoms of screwworms once again staging a fiesta in American flesh.

UPDATE June 18: The U.S. Department of Agriculture has announced a new plan to block the return of the screwworm, using Knipling and Bushland’s sterile fly technique.

Richard Conniff’s latest book, Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion, is now out in paperback. His other books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

And dumb.

Fascinating and outstanding piece! I was completely unaware of that story. An excellent of the value (and hard work) of basic research.