by Richard Conniff

(Note: This is one of my favorite stories, from a trip to Botswana and Namibia, in 2001.)

We found the leopard after dark. She was lying in the grass when the spotlight revealed her profile. Her massive shoulder muscles bulked out like a Janus face at the back of her neck. She got up and walked toward our vehicle and looked straight up at us as she slinked past, bathed blood-red by the filter on our light.

The guide recognized her as the daughter of a female he routinely followed. She was two years old, and the big, lumbering Land Rovers of the nearby lodge were as natural to her as elephants. She began to hunt, with three vehicles idling 50 yards behind her, through a thin forest of mopani trees. When the slink shifted unmistakably to a stalk, all the engines shut down and the lights went out. There was no moon, just starlight. A small herd of impalas stood off to the right, barely visible through binoculars. No one knew where the leopard was. It was an eerie moment, the guides whispering, everyone waiting for something to die.

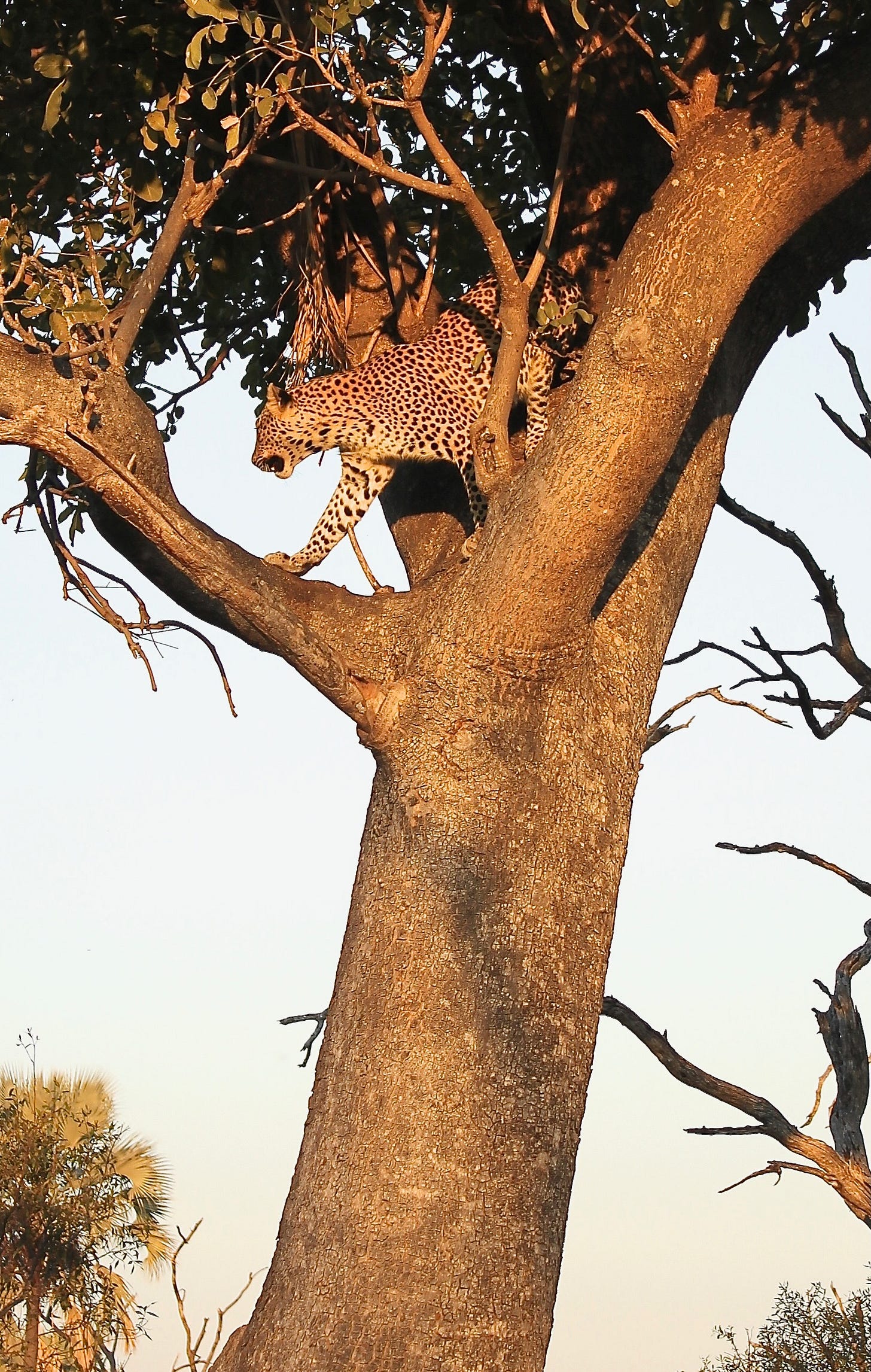

Suddenly, a commotion broke out on the right. The spotlight blinked on and caught the spectacle of the leopard up a tree leaping from one branch to another as four or five barn owls screamed "Chee-chee-ee" and tumbled away in a panic of flashing white underwings. The impalas barked in alarm, a sound like a short, wet sneeze. A couple of terrified baboons yelled "Wah! Wah!" And every human in earshot exhaled.

Fear of leopards is entirely natural. We have an old and tangled relationship: our ancestors were living among leopards and sometimes being killed by them before we were even human. One archaeologist, noting that leopards frequently stash an impala or other prey up a tree, has argued that early hominids scavenged for food by raiding the leopard's larder. Leopards returned the favor. At the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria, South Africa, for instance, there's a 2-million-year-old hominid skull with puncture marks in the forehead precisely the breadth of a leopard's bite.

Our relationship is, if anything, even more tangled today. Leopards live like phantoms not just in deserts and jungles but even within the limits of major cities. Not long ago, biologists trapped ten leopards in a single park on the outskirts of the city of Dar es Salaam, capital of Tanzania. In Nairobi, Kenya, population three million, I recently visited a prison compound where a leopard had slipped in and plucked a guard dog off its chain. By stealth and wit, leopards have managed, alone among big cats, to thrive in modern Africa. They are invisible, and they are everywhere.

At a remote air strip in the arid pink hills of Namibia, on Africa's southwestern edge, I watched one day as a Cessna 206 touched down and rolled slowly to a stop. Two Bushmen trackers climbed out. They were slight, mild men with small ears and prominent rounded cheekbones. Their hair was bunched in tight little naps. Each of them carried a sashlike hunting bag made from steenbok skin, worn soft with heavy use. Each bag contained a small bow strung with sinew, and a quiver made from PVC pipe.

The pilot, a Namibian leopard biologist named Flip Stander, introduced them to me. This was a chore. The Ju/Hoan language of the San, as the Bushmen are formally known, uses four distinct clicks, beginning at the front teeth and moving toward the back of the throat, for which English has no equivalent in spelling or pronunciation. Tkui (pronounced with a dental click, like tht-Kooey) was the younger of the two, about 35, and sharper-eyed. Txoma (pronounced with a mid-palate click, like tkk-Tcoma) was about ten years older, slower and more judicious. As trackers, they were fluent not just in the Ju/Hoan language of clicks and murmurs but also in the very subtle and more ancient language of footprints.

We spent the next few days driving through the dry, hilly countryside in Stander's 17-year-old truck, with Tkui sitting on a plank above the left headlight to scan the dusty road for footprints. We drove in second gear, at 10 or 12 miles an hour, and mostly saw the usual litter of antelope tracks. Then Tkui held up his hand, and we got out to examine some leopard prints. They belonged to a female we'd seen the day before.

"How can you tell?" I asked.

Tkui looked at me. "Can't you see?" he said.

Stander, who was translating, tried to explain. "It's a bit like seeing people walking on the horizon and you know that one's your wife. But could you say how? It's the way she walks, but how would you describe it?"

I contemplated the inscrutable indentations in the sand and pressed him to be a bit more specific. "When asked, they'll say it's a variation in the pads. But it's also a variation in the way of walking." I made him ask anyway, and Tkui tapped his right knee, then gestured with the closed knuckle of his hand as if taking steps. "The angle of it," Stander explained. The leopard's right hind foot is splayed slightly outward.

"The most difficult thing about tracking is individual identification," Stander told me. "There's nothing else that requires so much skill and intelligence." He once tested a team of four San trackers for a biological study and found they could identify individual animals (including humans) by their footprints 93.8 percent of the time. Once, when he was living out in the bush, Stander said, some canned food disappeared from his hut. The local women took one look at the footprints and named a teenager, who, on being tracked down some 20 miles away, admitted his guilt as if they had him by his DNA.

This habit of reading the world through the language of footprints is deeply ingrained. One night, an African wildcat stole some meat Tkui and Txoma had stored in a tree. The next morning, as if it were the most logical thing in the world, the two men followed the trail to the cat's lair and took the meat back. Txoma later told me that when a toddler becomes bored, his elders set him to following the trail of an ant. Tracking is simply what the San do.