Why We Need Federal Workers

A true story of how one of them saved us from a horrific national catastrophe

by Richard Conniff

Republicans have a rich history of smearing federal workers. They have been serving up slurs, like hamburgers at McDonald’s, by the billions and billions, going back at least to 1950. That’s when the thuggish Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy made his evidence-free and eagerly homophobic accusation that the State Department was staffed by “prancing mimics of the Moscow party line.”

Today the prancing Moscow mimic occupies the White House, having campaigned on the idea, also evidence-free, that government workers are “destroying the country. They’re crooked people. They’re dishonest people.” As president, Donald Trump, the convicted felon and adjudicated rapist, seems to be intent on following through on his threat that “they’re going to be held accountable.”

So here is the one good thing about his shambolic second presidency: By firing so many federal workers, so randomly, Trump is giving all Americans an unintended rapid-fire lesson in just how essential federal workers are to our health, safety, financial security, and standing in the world.

At least some of his fellow Republicans seem dimly to get it, if only because most federal employees work in districts dominated by Republicans. Indeed, some of Trump’s own cabinet members have noticed the damage being done. “What am I supposed to do?” Sean Duffy, Trump’s frustrated transportation secretary, reportedly demanded, during a tense cabinet meeting confrontation with Trump hatchet-man Elon Musk. “I have multiple plane crashes to deal with now, and your people want me to fire air traffic controllers?”

The reality is that we need our federal workers, in ways large and small. To understand just how true that is, think about Frances Kesley, and the catastrophe avoided because she did her bureaucratic work honestly. The story is worth re-telling as a stand-in for the many other civil servants who carry out their duties on behalf of the American public namelessly and expecting only to be forgotten.

Kelsey, a Canadian by birth, was a 1950 graduate of the University of Chicago School of Medicine, with doctorates and practical experience as both a physician and pharmacologist. But instead of pursuing a lucrative career in private practice, she chose to work for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), reviewing new drug applications.

On December 1, 1960, the application landed on Kelsey’s desk for a new European sedative being introduced to the American market under the brand name Kevadon, as a treatment for anxiety, sleeplessness, and morning sickness. The applicant was William S. Merrell Pharmaceuticals, which had acquired American marketing rights from the German drug company Chemie Grünenthal.

Merrell was so confident of approval that it had already stocked up with 10 million Kevadon tablets ready for immediate distribution. The review process then was heavily weighted in favor of drug companies, according to the 2024 biography Frances Oldham Kelsey (Oxford University Press), by Cheryl Krasnick Warsh. The FDA had just 60 days to reject or accept an application, or the drug automatically entered the market.

Merrell, moreover, was perfectly willing to show up in the FDA offices to hector and cajole on behalf of its product. Chemie Grünenthal was likewise the sort of place, Warsh writes, where “ethics never stood in the way of profits.” Its executives included one of the architects of the Nazi extermination policy in Poland, the chief doctor at three Nazi concentration camps, the co-inventor of the nerve toxin Sarin who was convicted at Nuremberg for using slave labor from Auschwitz, and a physician who had conducted fatal medical experiments at Buchenwald.

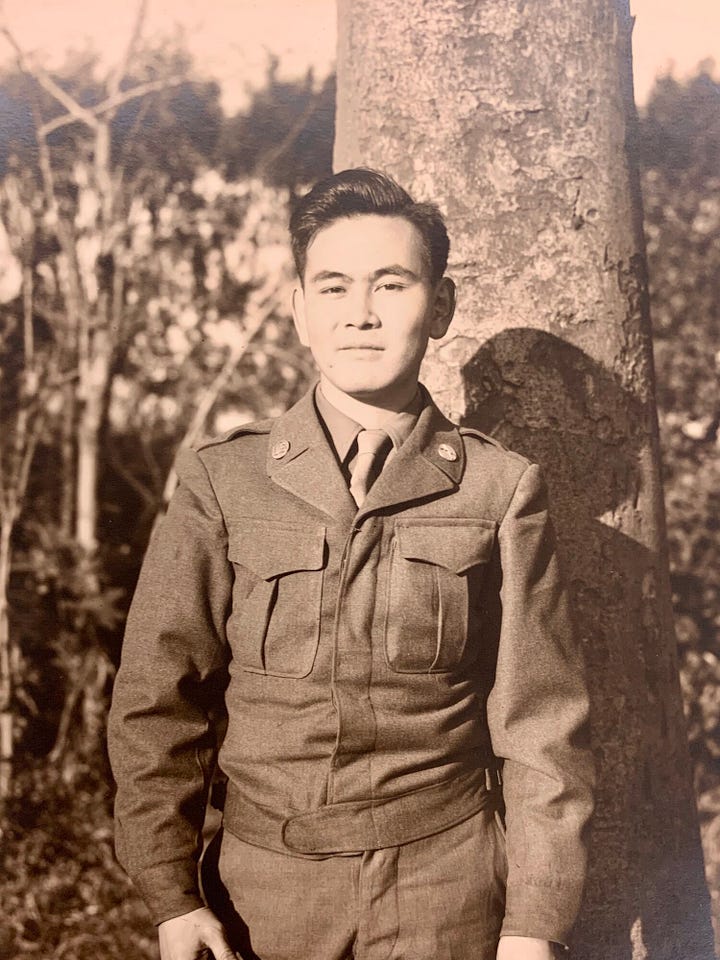

All three FDA reviewers had personal reasons not to risk taking a stand against such powerful interests. The day Merrell’s application arrived, Kelsey, who would be responsible for reviewing the clinical studies, had been on the job just three months. That would make her a candidate for firing under the present-day Trump/Musk regime, and a probationary employee at any time. She was also a woman in a very male world. Lee Geismar, who reviewed the chemistry studies, was also a woman, and a Jewish immigrant who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. Jiro Oyama, who reviewed the animal studies, came from a Japanese-American family interned during World War II.

All three had sworn an oath, however, to “well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter.” So Geismar pointed out errors of translation from the original German in Merrell’s slapdash application. Oyama noted that the drug did not seem to be metabolized normally in animal studies. Kelsey saw that Merrell’s limited human studies had skipped over normal procedures for clinical trials and produced testimonials rather than hard data. She also suspected that the inability to metabolize the drug normally in adults would be even more problematic in the undeveloped kidney of a fetus. Merrell withdrew its application and promptly submitted an amended version.

Other issues turned up, notably peripheral neuritis, a painful and probably irreversible tingling in the hands and feet of patients who had taken the drug. Kelsey requested further information about Merrell’s human studies and wrote a letter suggesting that Merrell had failed to disclose its awareness of Kevadon’s neurological toxicity. The FDA team sent back the Kevadon application again in March, and in June, 1961.

Merrell then threatened to sue the FDA Commissioner personally, according to Warsh, “if Kelsey did not release the drug.” That summer, the company waged a campaign on behalf of its product with phone calls, sternly-worded letters, and personal visits to Kelsey and her superiors. “Most of the things they called me you wouldn’t print,” Kelsey later recalled. But no one at the FDA seems to have joined in the name-calling, or otherwise pressured her to relent.

In September, Merrell managed to stage a debate pitting its own researchers and outside experts against Kelsey and other members of the FDA team. A Johns Hopkins pharmacologist who had participated in the company’s clinical studies urged the FDA to “give the drug a whirl” on the market. It would later come out that Merrell had already done just that, with almost 20,000 American patients receiving the drug from their doctors as part of a marketing campaign begun even before its FDA application had been properly submitted. The FDA again deemed the Merrell application incomplete in August and October, 1961.

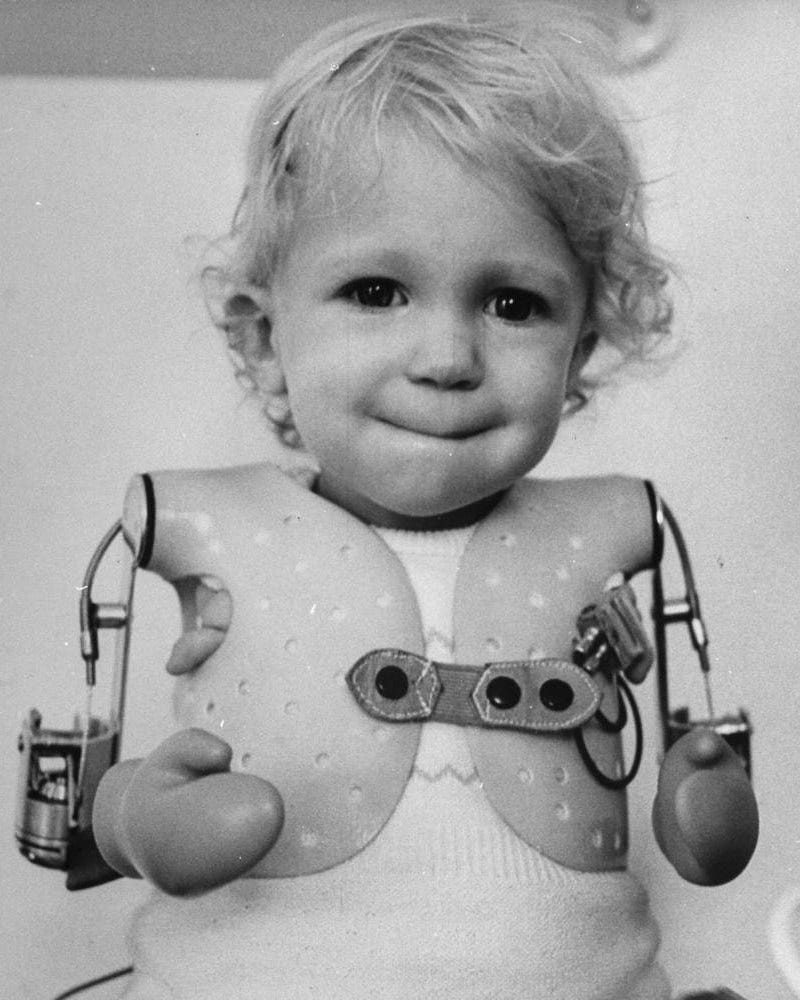

The drug, also known by its generic name thalidomide, had at that point already been on the European market since 1957. Reports of severe birth defects in children of patients using it had begun to turn up in Germany, England, Australia, Canada, and other countries. Infants were being born with no legs, or with their hands growing directly from the shoulders, like flippers. Hence the condition was known as phocomelia, from the Greek words meaning seal-like limbs. Others miscarried or were born too severely deformed to survive.

An American doctor who had seen only two cases of children born without limbs in her entire career came home from a European tour to report that some physicians there were now seeing 50 or 60 such cases. Accounts appeared in medical journals and then, in late 1961, in the general press. In Germany public health officials pulled thalidomide from the market at the end of that November. Incredibly, Merrell continued to push for American release of thalidomide until, worn down by Frances Kelsey and the FDA team, it finally withdrew its application in March, 1962.

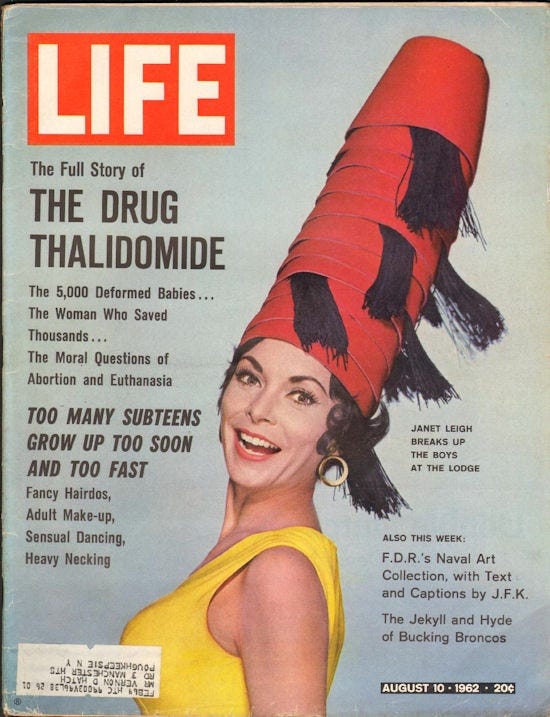

Americans first learned of the FDA’s defense of their health in July that year, from a front page article in The Washington Post under the headline “Heroine of FDA Keeps Bad Drug Off Markets—Linked to Malformed Babies.” Then, in its August 10, 1962, issue, Life magazine pulled in pre-teen readers, myself among them, with an enticing cover photo of the actress Janet Leigh, and maybe also an unrelated coverline promising sensual dancing, heavy necking, and growing up too fast.

Instead, the reader landed, aghast, on a lead story featuring haunting pictures of horrifyingly damaged children.

In her book, Warsh puts the damage at “an estimated 100,000 newborns … affected by thalidomide globally, suffering from neurological disorders, cardiac issues, or other serious birth defects, with approximately ten thousand of them” born with deformed extremities. In the United States, only 17 cases occurred, caused by Merrell’s “investigational use” of the drug.

The resistance to thalidomide by Kelsey and the FDA team had taken place out of the public eye, even as U.S. Senator Estes Kefauver (D-Tennessee) was holding highly public hearings on the drug industry’s deceptive marketing, shoddy products, and excess profits. Kefauver had introduced legislation aimed at dramatically increasing the FDA’ s ability to regulate drugs and medical products. But Republicans had predictably opposed the bill as a license for bureaucrats to interfere in the free market. They proposed amendments to water it down. A spokesman for the American Medical Association characterized the bill’s supporters as “mavericks, the discontented, discharged employees, scientific Leftists.”

The FDA’s stand against thalidomide changed all that. Just eight days after the Washington Post broke the story, Kefauver nominated Kelsey on the Senate floor for the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. Within a month, President John F. Kennedy was putting the medal around Kelsey’s neck in a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, and praising her “exceptional judgment” and “steadfast confidence in her professional decision” in preventing “a major tragedy of birth deformities in the United States.” Congress soon voted down the Republican amendments to the Kefauver-Harris Drug Act of 1962, which became national law that October, empowering the FDA to regulate drugs based on both safety and effectiveness.

So how is all this relevant to the FUBAR world of Donald Trump and Elon Musk? What does it have to do with the current spectacle of wildly inept mass firings of federal workers? I am thinking, for instance, of the mistaken firing of federal workers responsible for Ebola prevention, or of workers who maintain nuclear weapons security, or of weather staff charged with issuing timely hurricane and tornado warnings.

Every time I see another group of dispirited federal workers forced out of their offices on short notice, the same question comes to mind. Some uneasy version of this question probably runs through your mind, too:

Is that the Frances Kelsey of our future being shoved out the door?

UPDATE: In an earlier version, this story was headlined “One Good Thing About Donald Trump.” I have changed it because, at this point, even his mother would not imagine for a moment that there is anything good about Donald Trump. If you want a sense of how many people his decisions will kill this year alone, I highly recommend today’s column in the New York Times by Nicholas Kristof: “Musk Said No One Has Died Since Aid Was Cut. That Isn’t True.”

Additional reading:

Frances Oldham Kelsey, the FDA, and the Battle Against Thalidomide, by Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, Oxford University Press

I haven’t read this one but hear good things about it:

Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and its Hidden Victims, by Jennifer Vanderbes, Random House, 432 pages.

There are other stories of great federal employees I’d love to tell. But meantime, take a look at the Golden Goose Award, a scientific response to the Golden Fleece Awards.

To read about one of favorite U.S. federal workers, who instigated the worldwide campaign to eradicate smallpox everywhere, forever, check out my book Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion (MIT Press), out this week in paperback.

thank you, sir we needed that.

more piwer to your typing fingers.

as Chief Dan George says in the Outlaw Josey Wales, " endeavour to persevere"

Well done. There are similar stories elsewhere, especially related to the environment.