by Richard Conniff

It’s Earth Day, and this quote from Rachel Carson comes to mind:

"Man's attitude toward nature is today critically important simply because we have now acquired a fateful power to alter and destroy nature. But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself."

So I’m going to feature an important, but largely forgotten, figure in that war. He was one of Carson’s leading critics, but also, oddly, a member of the Sierra Club. His work has altered everything from the food you put on your tables to whether you’ll survive an infectious disease.

On Christmas Day in 1948, a drug company biochemist named Thomas H. Jukes slipped away from his family and made the short drive to his workplace at Lederle Laboratories in Pearl River, New York. A small experiment with chickens was in progress, and the subordinate who would normally have weighed and fed the birds was home for the holiday.

As he made his rounds, Jukes noticed something peculiar. In one group of a dozen chicks, the feed was being supplemented with a pricey new liver extract, which was certain to make those birds gain weight much faster than normal. But Jukes was puzzled to see that birds in another group were growing even faster than their liver-fed counterparts. The only thing being added to their feed was a new antibiotic called aureomycin. “The record shows,” Jukes later wrote, staking his claim to the discovery, “that I weighed the chicks on Christmas Day, 1948.”

No one understood how or why an inexpensive antibiotic could cause animals to put on meat more rapidly. (Even now, researchers talk only about “proposed possible mechanisms” to explain the phenomenon.) But after some quick follow-up work in the field confirmed the finding, Lederle rolled its product out onto the agricultural marketplace. It was the beginning of a vast uncontrolled experiment to transform the biology of the animals we eat--and perhaps also the biology of the humans who eat them. Antibiotics added to feed at very small, or sub-therapeutic, levels would quickly become a standard tool for rearing food animals, so much so that, even now, about 80 percent of antibiotic sales in the United States go to livestock production rather than to human health care.

The food industry has long argued that any attempt to limit use of antibiotics in livestock feed would be an agricultural disaster—or at least the end of affordable meat. But critics are applying increasing pressure on the industry to address its share of the blame for an epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections that kills hundreds of thousands of people worldwide each year.

So how did antibiotics get into our food supply in the first place? It was largely the work of one otherwise highly esteemed researcher. It was also a classic case of economic interests distorting scientific judgment. Or as Upton Sinclair once wrote: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

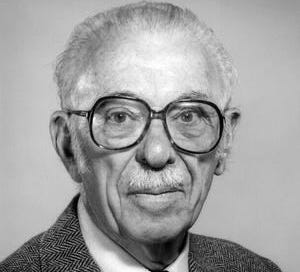

Thomas H. Jukes (1903-1999), the man who turned antibiotics into animal feed, was a remarkable biologist, an old school environmentalist, a life member of the Sierra Club, an enthusiastic outdoorsman, and in later years, when he was a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, a pioneer in the then-new science of molecular biology. He was also an ardent defender of science, or at least his view of science. He wrote hundreds of opinion pieces, often polemical, on topics of the day, and, among other achievements, fought effectively to prevent the introduction of creationism into California schools. He also campaigned against Laetrile and other quack cancer cures, and lambasted Linus Pauling for touting massive vitamin doses as a panacea.

But Jukes had formed his ideas in an age of medical miracles, and firmly believed in the power of science to conquer sickness and hunger. So he also defended use of DDT against malaria in the strongest possible language—even calling attempts to ban the insecticide “unquestionably genocidal.” When the prescription drug DES, or diethylstilbestrol, became notorious in the 1970s for causing birth defects and cancers in young women, Jukes argued for its continued use as a growth promoter in cattle, saying the risk to consumers was minuscule. He took what he saw as a rigorous, evidence-based approach to such questions, in contrast to the supposedly “emotional” language of the emerging environmental movement. He often quoted the Renaissance medical writer Paracelsus, who believed that everything and nothing is poisonous: “The dose alone makes the poison.”

His fierce opposition to environmental critics undoubtedly reflected his own career history. Before moving to Berkeley in 1963, Jukes had spent his most productive years, from his mid-30s to his late 50s, in the pharmaceutical industry. He worked as a biochemist for Lederle Laboratories, a division of American Cyanamid, at a facility just outside New York City that now belongs, by a series of mergers, to Pfizer. There, his own writing indicates, he was considerably less rigorous about insisting on detailed experimental evidence.

(to be continued tomorrow)