To celebrate the opening today of the Yale Peabody Museum, after a four-year closure for renovation and rebuilding, I’m posting a chapter from “House of Lost Worlds,” my history of the museum, about one of its lesser known heroes. The chapter opener went up yesterday, and I’ll continue posting here through the week.

by Richard Conniff

Over the next few years, John Bell Hacker repeatedly proved his worth by collecting in all seasons and circumstances, in the process developing an excruciating and chronic case of inflammatory rheumatism, but also sending hundreds of specimens of Brontotherium back to New Haven. These were huge mammals from the late Eocene, rhino-like in appearance, but as big as African forest elephants, and with a pair of horns like a goal post above the nose. Indians had seen the fossils and described the hoofbeats of these enormous animals as the source of thunder. Hence Marsh’s name Brontotherium, or “thunder beast.” He wanted as many specimens as possible for a monograph he hoped to publish, like the one he had recently completed on the Dinocerata, another order of huge hoofed mammals.

In 1887, Hatcher found time to court and marry. But given his unstoppable drive as a paleontologist, and Marsh’s eagerness to take full advantage of it by keeping him in the field year round, Anna Peterson Hatcher, a Swedish immigrant, must have come to the marriage with a prudent mix of bottomless patience and low expectations. Fossils were Hatcher’s true love. They were the remains of creatures that had been dead and extinct for millions of years, and yet no woman ever faced a more formidable rival. Annie kept house, often on her own, in a Nebraska town aptly named Long Pine.

Still in his mid-twenties, just four years out of college, Hatcher now demonstrated the combination of skills that would win him acknowledgment as “the best and most successful palaeontological collector whom America has ever produced.” First among these skills was a genius for reading rock. Out in what he called “the Ceratops beds” of southeastern Wyoming (the Lance Formation to modern paleontologists), primordial animals had fallen and been buried by a current sweeping across a shallow, marshy landscape. Hatcher could determine the direction in which the current had flowed roughly 65 million years ago by noticing the sand built up on one side of an exposed bone, and the fossilized plant stems and leaves that had sunk and been buried after being caught up in the resulting eddy on the opposite—downstream--side. That sort of clue could lead him to bones in places where a less observant paleontologist might never have bothered to look.

His “marvelous powers of vision” were “at once telescopic and microsopic,” the paleontologist W.B. Scott wrote, and he displayed both with “a dauntless energy and fertility of resource that laughed all obstacles to scorn.” The Lance Formation was strewn with remains of diminutive Cretaceous mammals. But it could take a man half a day of conventional searching, bent at the waist, or on hands and knees, to come up with a single tooth. Hatcher turned to screening as a more efficient method, and at one point he had thirty wagon loads of quarry sand waiting to yield up their mammal parts. Then it occurred to him to inspect the contents of nearby harvester ant mounds, running them through a small flour sifter. Forager ants of this species spread out across the landscape collecting seeds to eat and also pebbles and other small objects to insulate the mound. Hatcher found he could recover as many as 300 teeth and jawbones from a single mound. Thereafter, in areas that lacked harvester ants, he would introduce a nest of them, and check back on their work a year or two later. One such introduced nest yielded 33 fossil mammal teeth.

Hatcher was also unequaled in the care and the mechanical aptitude he brought to the delicate business of extracting the much larger specimens he found. “The greatest possible credit is due to Mr. Hatcher not only for the discovery of these rare animals, but for the enormous undertaking of taking up and packing specimens of such weight and dimensions,” wrote Charles E. Beecher, a Peabody paleontologist who was working with Hatcher in the summer of 1889. “Out here, mechanical facilities are few and such large undertakings are only accomplished by the hardest work and perseverance under many difficulties and disadvantages.” Another writer remarked on Hatcher’s ability to extract “huge and weighty objects from difficult positions,” daring “great physical risks and even death, when alone, far from human companionship, in extracting masses from their original position and moving them by a skillful arrangement of levers to points where they could afterwards be taken up,” in one case handling “a block of rock weighing nearly a ton without the assistance of other men.”

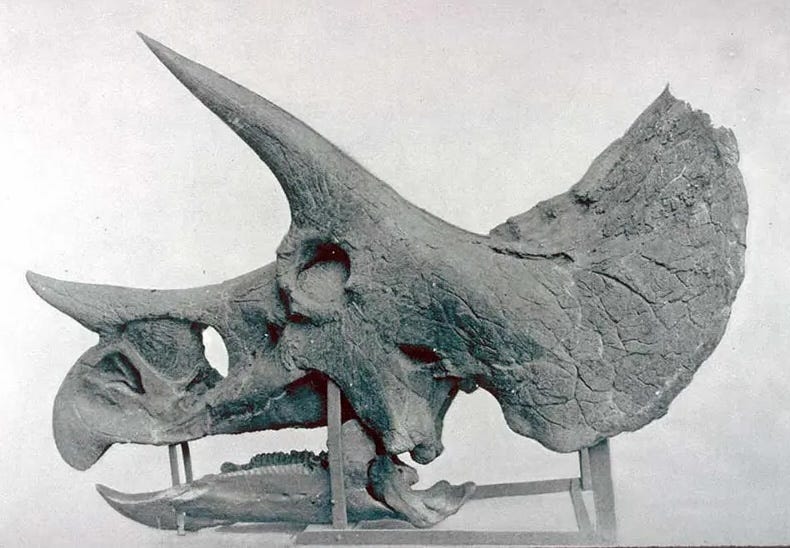

By the end of that July, 1889, Hatcher had two more gigantic skulls, each weighing about 3000 pounds, counting the stone in which they were embedded. “They are certainly most marvelous creatures,” Beecher wrote, “with their scalloped and cornuted frill, their big horns and extravagant beaks. These specimens will make a wonderful and startling exhibit.” But first Hatcher had to haul them up, intact, out of steep ravines, crate them for long-distance travel, and deliver them by wagon 30 or 40 miles across rough country to the railroad at Lusk, a three-day trip. “But I have an abundance of ‘self conceit’ & it does not frighten me at all,” wrote[Hatcher, “& you may be sure that we will get them out & packed all o.k.” (“It would make your hair stand on end, to see the terrible places where Hatcher will take a heavily loaded horse,” a collector who worked with him remarked. “Places you would not imagine it possible for a horse to go at all.”) The following year, working in continuous rain and snow, he extricated a skull and its surrounding rock weighing 6850 pounds, and shipped it in a crate that was ten feet long and five wide. “I would not be afraid to tackle one now that weighed ten thousand pounds,” he remarked afterward.

(To be continued)