The Unnatural History of Alice in Wonderland

How great children's writers grew giddy in the age of discovery

by Richard Conniff

Lately, I have been buying copies of a favorite old children’s book, in an edition that’s now out of print, for my grandchildren. That book suggested this story. It’s about funny books, yes, but also about our sense of wonder, surprise, and delight in the strangeness of the natural world.

When our children were small, we often read them Edward Lear’s The Jumblies, a not very edifying book of nonsense that we all loved. The Jumblies were wildly impractical souls who

… sailed away in a Sieve, they did,

In a Sieve they sailed so fast,

With only a beautiful pea-green veil

Tied with a riband by way of a sail,

To a small tobacco-pipe mast …

Back then, I was often away from home for weeks at a time, traveling in distant countries with biologists whose work sometimes required them to do the equivalent of sailing in a sieve. One botanist, for instance, recalled flying out of a war-torn corner of Colombia in a cargo plane that also carried a pig tied to a 55-gallon drum of gasoline. The Jumblies would have been right there, and probably flicking ashes from their cigars.

But it never occurred to me that there might be a direct connection between the two worlds of nonsense verse and biology. Then one day I picked up an old print of a tropical pigeon species and noticed the “E. Lear” in the bottom corner. Though he is celebrated today mainly as the author of such works as The Owl and the Pussycat, Lear had started out as a naturalist. His first book, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, drew favorable comparisons with Audubon when he published it in 1832, at age 19.

Like many naturalists, Lear described the natural world not just in literal-minded scientific detail, but also in fanciful doodles and verse. And when this blossomed into books for children, he often shipped his characters out, like naturalists, on wild explorations to the back of beyond. He also had them devote considerable energy to collecting the oddities of the country:

And they bought a Pig, and some green Jack-daws,

And a lovely Monkey with lollipop paws,

And forty bottles of Ring-Bo-Ree,

And no end of Stilton Cheese.

Beatrix Potter, best known for The Tale Peter Rabbit, also entertained early ambitions to be a serious naturalist. Mushrooms were her specialty, and at age 31 she submitted a handsomely illustrated paper On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae to the Linnean Society, the same venue where Darwin and Wallace’s theory of evolution by natural selection had first appeared 40 years earlier. Potter’s paper was accepted, but as a woman, she was not allowed to present the paper herself, or even attend the reading. Unsurprisingly, she turned to children’s books instead. (Her books have since sold more than 250 million copies, while the men who excluded her have been largely forgotten.)

The nineteenth-century fascination with nonsense was largely a byproduct of the heyday of natural history. It wasn’t just that European naturalists of that era were swarming over the world their nations had colonized. A passion for identifying mosses, ferns, and even limpets had also seized the imaginations of the rising middle class at home.

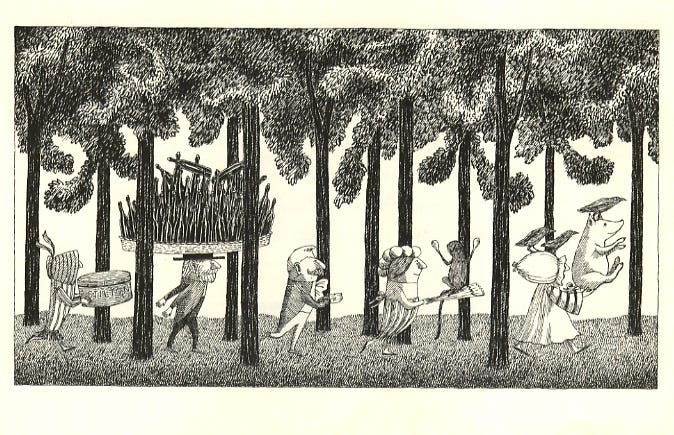

The twin themes of exploration and taxonomy, the French scholar Jean-Jacques Lecercle wrotes, in his 1994 book Philosophy of Nonsense, were “present in the genre as a whole, even in Lewis Carroll, who had no special interest in the subject. The reader of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is in the position of an explorer: the landscape is strikingly new … and a new species is encountered at every turn, each more exotic than the one before. Nonsense is full of fabulous beasts, mock turtles and garrulous eggs.”

Such fanciful creatures sometimes turned up even in serious scientific work. In his History of British Star-fishes, and other animals of the class Echinodermata, for instance, the naturalist Edward Forbes began one chapter with an illustration of Cupid in a sea-going chariot drawn by a pair of sea creatures with bodies like snakes and heads like sea urchins (they were Ophiuridae). Another chapter ends with Puck playing his pipe for a couple of dancing brittle-stars, one of which actually rests the back of a “hand” against out-thrust “hip.” Elsewhere, he drew a stingray smoking a pipe and winking.

In Lecercle’s view, Charles Darwin himself could sound as whimsical as Lewis Carroll; for instance, when he wrote about pulling the tail of a lizard in the Galapagos: “At this he was greatly astonished, and soon shuffled up to see what was the matter; and then stared me in the face, as much as to say, ‘What made you pull my tail?’” Likewise, in Patagonia, Darwin and his companions communed with the camel-like guanacos: “That they are curious is certain; for if a person lies on the ground, and plays strange antics, such as throwing his feet up in the air, they will always approach by degrees to reconnoitre him.” Darwin was only 23 at the time, not the gloomy eminence of later years, but Lecercle likes the idea “that the famous scientist should behave like Lear’s ‘Old Man of Port Grigor’, who ‘Stood on his head till his waistcoat turned red.’ ”

So what’s the explanation for this intimate connection between science and nonsense?

Scientists are of course somewhat human. So perhaps it should be unsurprising that they can sometimes have fun with — or make fun of — their own work. But in the 19th century that work — describing species no one had ever imagined — was also often fantastical. It is hard for us now to appreciate just how strange and wondrous the world seemed. It was as if someone you know had joined an expedition to Alpha Centauri and come back years later with first-hand accounts of Wookiees, Ewoks and Kowakian monkey-lizards. But in the great age of biological discovery, the returning travelers actually brought back specimens, sometimes still living. Their weird creatures were real.

When they told their tales about riding on the back of a caiman, or waking up from an al fresco nap to find that a gigantic condor had mistaken them for cadavers, it must have seemed even to them that they had traveled through the looking glass.

Near the end of his life, with his adventures as an explorer far behind him, the great field naturalist and evolutionist Alfred Russel Wallace built a house in a Dorset village for his daughter, to be joined by his wife after his death. He named it Tulgey Wood, after the haunt of the jubjub bird and the frumious bandersnatch in Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”:

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

Nowadays when I read that poem, I sometimes imagine Wallace hiding behind a tree in Tulgey Wood, peering out and chortling to himself — “Oh frabjous day! Calloo! Callay!”— at the magical but very real world he had been granted the privilege to know.

Richard Conniff’s latest book, Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion (MIT Press), is now out in paperback. His other books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

Oh, to have been a naturalist in the 19th century! And what a treasure that print by Lear! To have such talent at the age of 19! Your essay is bringing out lots of exclamation marks from me :) Thanks for another delightful read!

The story of Darwin and the guanaco was new to me, but must be the inspiration of a scene in The Island by Robert Cushman Murphy where he uses that trick to attract a Laysan Teal. If I recall correctly….