By Richard Conniff

The job opening is for travel in the East African bush, on foot, close enough to keep an eye on a pride of lions. That is, close enough at times to identify individuals by counting their whisker spots, without the help of binoculars. The applicants are Maasai herders, men with underfed, almost skeletal builds, many of them with past experience spearing lions to death in retaliatory or ritual killings.

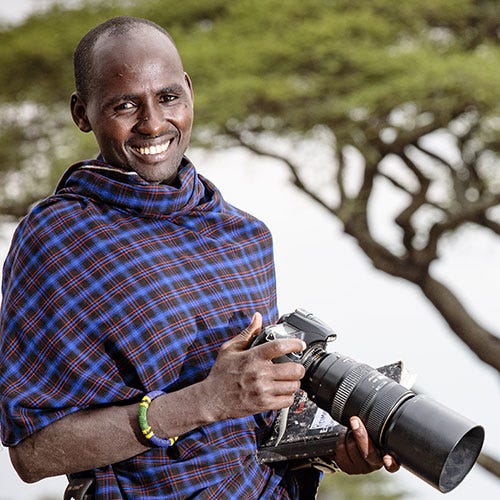

This time, though, they get no weapons, and the job is to protect the lions, and also their Maasai neighbors and livestock. They’re called ilchokuti, meaning “guardians” or “caretakers” in the Maa language. Walking with the lions earns them $100 to $120 a month from the Kope Lion Project, a conservation nonprofit. It’s big money in the dry, scrubby habitat of rural northern Tanzania. Each of the 28 ilchokuti hired so far works a 30- or 40-square mile area around the community where he lives, in the corridor between two of the most celebrated wildlife areas in the world, Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Crater. The ambition, according to Ingela Jansson, founder of the Kope Lion Project, is to create “a corridor of tolerance” for predators, where intolerance is now the rule

That corridor is about 50 miles long. On one end, Serengeti National Park is home to more than 3000 lions, the largest remaining population in Africa. On the other end is the crater, home to a flourishing population of about 80 lions, which are strictly protected for the lucrative tourism trade. But the crater is only about three percent of the 3200-square mile Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Beyond the crater rim, in places most tourists never visit, lions have largely vanished. The lions inside the crater are cut off from other populations and increasingly inbred as a result.

It’s a microcosm of what’s happening across Africa, where the total lion population is down from 200,000 animals in 1900 to around 24,000 today, according to a recent report from the cat conservation group Panthera, and Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit. Lions are already extinct in 95 percent of their former range—and even within many protected areas.

Trophy hunting tends to get the blame on social media. And it can be part of the problem, particularly in Tanzania, which has traditionally paid scant attention to science in establishing rules for the lucrative game hunting business. But even in neighboring Kenya, where trophy hunting has been banned for the past 40 years, lions now face extinction. The larger problem is that lions are being crowded out of sub-Saharan Africa by people and their livestock. Within the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, for instance, the human population has grown thirteen-fold, from 7000 to 90,000 people, since 1960. Almost all of them are impoverished rural herders focused on protecting their livestock and feeding their families, and they tend to be hostile to lions.

Hence Ingela Jansson’s first encounter with the Maasai. As a researcher tracking radio-collared lions in Serengeti National Park, she recalls, “I hadn’t met the Maasai before. They’re in the park illegally, so they’re avoiding you, and you’re avoiding them because you’re totally on your own.” But in April 2010 a collared lioness she was tracking crossed the park border and Jansson followed. She found a group of 18 young Maasai warriors standing around the body of the lioness and two other lions, which they had speared. “I took pictures from my Land Rover and called the police,” says Jansson.

The men carried off the collar as a trophy, not realizing that its radio signal gave away their movements. Together with the police, “we tracked them into the mountains for three or four hours and got them around 6 p.m.,” Jansson recalls. “It wasn’t a very nice thing to see people being arrested. They were whipped and dragged by the hair and I was the cause of this whole event.”

The following year, Jansson, a tall, lean, 40-something Swede, then pursuing her PhD, launched the Kope Lion Project. She modeled it on the Lion Guardians, a conservation group across the border in Kenya that also hires Maasai warriors as intermediaries between lions and the local community. But it took her another year to make her first hire. “People came up to me and said, ‘Weren’t you the one who arrested those people?’ It was well known.” Gradually, though, she became a familiar part of the community.

From the crater, Jansson and I drove out about two hours to an area where lion killings are still commonplace. In the middle of nowhere, we met two ilchokuti, named Sandet and Kinyi , dressed in the traditional Maasai shúkà, a colorful sheet-like garment worn wrapped around the body. Jansson brought out a cooking pot, a container of frozen bean soup, and a handful of spoons for lunch. As Sandet built a fire and pushed the slowly-dwindling lump of frozen soup around the pot, they chatted amiably in Swahili about the two lions resting in the nearby brush, and about ice. He’d never seen anything frozen before. “It’s like a rock,” he said.

Many of the people Jansson hires have never traveled outside the area, and they know little beyond the traditional Maasai way of life. When I offered chicken from my box lunch, they said they’d never eaten it before. Beef, goat, sheep, and dairy are their standard menu items, to the point that they also do not typically hunt bushmeat. (They were happy to try the chicken, but not so happy, said Jansson, to tell their mothers.)

What they know is life in the bush, and lions. The ilchokuti track lions mainly by their spoor, or footprints, much as they once did to kill the lions. But now they stay nearby to steer off local herders, as a way of minimizing conflict. The ambition is for them to become guardians of the community, as well as of the lions.

They take the work seriously. Sandet once jumped in between a lioness and the cattle she was stalking, at a distance of about 40 yards. Everyone walked away intact (though hungry). Another ilchokuti had to chase lions off 18 goats and sheep that they had just killed, to return the carcasses to their owners. “Lions are very fearful of people on foot,” Jansson explained. “When they take a cow, they never linger by the carcass. They know they are in danger”—that is, from the Maasai.

Retaliatory killings are common, and so are ritual killings by young warriors. They slip away from their families on an agreed night, have a meal together and sleep, said Kinyi, who participated in “about eight” hunts before becoming an ilchokuti. The day of the hunt they do not eat or drink. When they find a lion, a group of 5 or 10 of them fan out in front of it.

“And then it comes to us, to attack, or to run through,” he said. “Why don’t they run the other way? I don’t know. They get so angry, they have to run to us.” The first warrior to spear the lion gets its tail as a trophy, the second gets a front paw, and both gain status in the community.

Now, as an ilchokuti, Kinyi’s job is to pick up rumors of a planned killing and intervene in time to stop it. That can be a matter of confronting warriors in the field and talking them down, said Jansson, or simply providing bad directions: “The lions were over there, you should go that way.” The year before, she said, the ilchokuti had stopped 26 ritual hunts.

After lunch, we nosed our vehicle into the nearby brush to see the lions sleeping there, but the dense, thorny acacia blocked us out. We headed out instead to search for another lion pride, with Jansson at the wheel of the Kope Lion Project’s beat-up, 15-year old Land Rover Defender. (“Next service 379,851,” it said, on a piece of masking tape stuck to the dashboard.)

Roimen Lelya[, who supervises the ilchokuti, joined us. He said he had participated in three kills before going to work for the Kope Lion Project. Asked how many men he knew who had been injured in these hunts, he said, “Ai-ai-ai-i!” and started counting. He stopped at 13 men, just in his own age group.

Now, he said, he prefers protecting lions to killing them. The pay is better, and the status is the same: Staying within walking distance of a pride of lions, minus the spear that Maasai men almost always carry, takes obvious courage. Being a protector of the community confers status, too. The job also clearly appealed to something more nuanced in the Maasai relationship with lions. The herders are genuinely enraged when lions kill their livestock. But lions are also part of their identity. “To hear the voice of the lion at night,” said Lelya, “is something people really enjoy here.”

The Kope Lion Project names local lions to encourage that sense of connection. “It’s easy to retaliate against lions,” said Jansson, “but not so easy to retaliate against Nayomi when you know her family history.” Jansson also encourages the sense that the ilchokuti work for the community. “If we have an issue with one of our workers, we don’t directly reprimand him,” she said. “We go in and talk with the community leadership. They're now seen as servants to the community.”

Is this enough to ensure survival of lions in the Serengeti-Ngorongoro corridor? Probably not, if the human population keeps increasing at its current rate, and if the Maasai continue to regard large herds of livestock as the mark of social status. But Jansson is hopeful. Many men in the younger generation are less interested in killing lions, she said. They want to go to town and get jobs. “A lot of the younger guys may not even know what a lion spoor looks like. Lions are disappearing, so they get less exposure to them.”

The Maasai devotion to livestock at the expense of the land is also slowly changing, she said. She mentioned a local elder with 2000 head of cattle, and hundreds of donkeys. “The children barely have shoes. They don’t go to school. But I think some people are beginning to question that sort of prestige. They are starting to recognize that large livestock numbers are the cause of the degradation of the landscape.”

A long-term solution, said William Ole Seki, a community liaison officer with the Kope Lion Project, would be to establish a wildlife management area, where the local people both participate in the decision-making and share in the benefits. It’s happened elsewhere in Tanzania, with varying degrees of success, but not so far around the tourism motherlode of Ngorongoro and the Serengeti. That may be partly because much of the revenue from tourism there now goes directly to the national government, he said, “and in past governments, a lot of it was embezzled.”

Late in the afternoon, in a part of the conservation area called Ndutu, Jansson stopped to teach a new ilchokuti how to use a radio-tracking receiver. We climbed back into the vehicle afterward and followed the signal a few hundred yards, where we found two male lions flopped out in the shade, sighing heavily in their sleep. Beside them was a Cape Buffalo, an animal with a normal body weight of about 1300 pounds and a reputation for big, bad-tempered ferocity. It was dead of course, twisted over onto its back and its horns. The lions had devoured its hindquarters.

The Kope team identified one of the lions as Lajola, meaning “the one who appears suddenly.” Nearby we found three more lions sleeping, and beyond them, another three. This was Nayomi’s pride, a Kope success story. It has grown to 16 individuals under the watchful eyes of the ilchokuti, said Jansson. Nearby three jackals angled for a safe way to get to the buffalo carcass, and beyond them a cackle of hyenas restlessly waited their turn, a reminder that lions and other big predators produce changes that shape entire habitats.

Driving back toward the crater next morning in my vehicle, we came to a junction, and Jansson said we should turn left to our destination, while she would get out and catch a ride in the other direction, back to Kope headquarters. When we protested, she explained that it would be easy enough for a blonde, blue-eyed white woman, a muzungu, to catch a ride. “The tourists will pull over to ask if they can help,” she said. She opened the door to step out, and a Maasai woman who was not having such an easy time catching a ride immediately recognized her. “Mama Simba!” she cried—the lion mother. We took the left turn and headed off, leaving Jansson among friends.

.

In 2022 I traveled with my son, his wife and three grandchildren to Panthera at Okonjima up to the San people and west to the Himba. Okonjima on a photo junket (safari but family only) around northern Namibia. Fascinated with the various animals and waterholes with countless species and hierarchies.

Thanks, Richard. I've been leading safaris in East Africa for 45 years (now stepping down after one last March), and I have seen the explosion of people in Ngorongoro and the overall decline of lions. I always enjoy your stories. I used to sell tons of photos as slides, but the monopolies of big photo agencies and the ease by which anyone can get new photos has killed that enterprise too. Now I focus on painting wildlife and writing, though AE may threaten those too.