by Richard Conniff

Adapted from The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton).

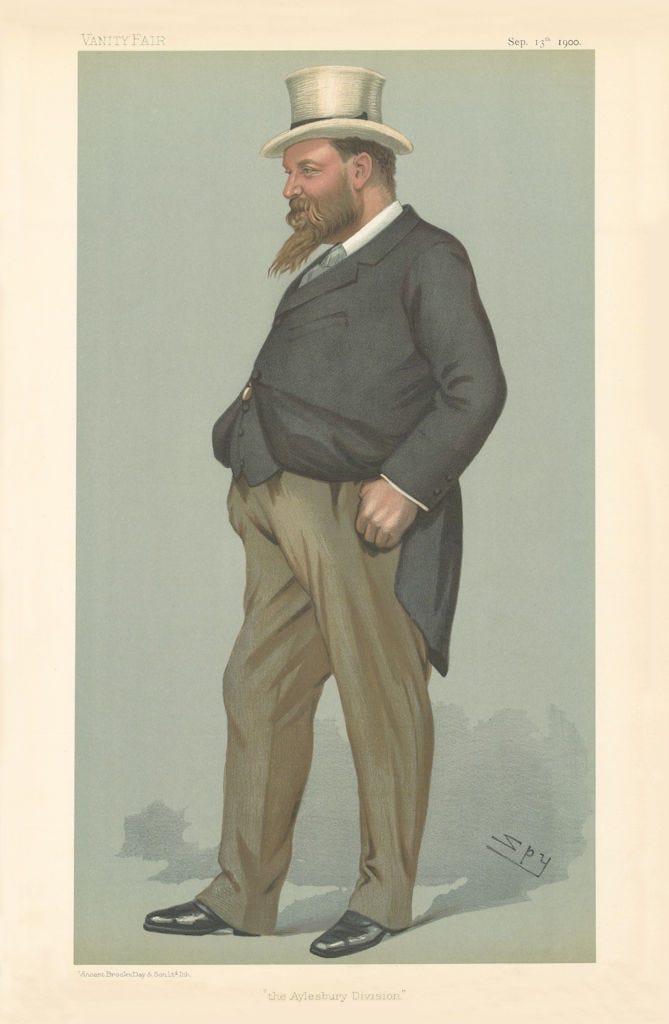

Walter Rothschild, of the banking dynasty, was one of the strangest, and most successful, naturalists in the history of the discovery of life on Earth. He was "a great stuttering bear of a man," 6-foot-3, weighing more than 300 pounds, according to one family member, and "could keep the whole house awake with his thundering snores." And this was a Rothschild house, with 20-odd bedrooms .

Everything about Walter was huge, including the flaws--quirks, rather--in his personality. He was, to begin with, hopelessly tied to his mother and lived his entire life on the nursery floor, a short stairway down from her apartment at the their country house at Tring, north of London. No doubt as a result, he was alternately shy, socially awkward, and arrogant.

In Dear Lord Rothschild, a biography, Miriam Rothschild, herself a noted entomologist, recalled her uncle's "almost infantile insouciance regarding other peoples' problems." She may have been thinking about the time when she was 13 and Walter, age 53, sized up her body type in a booming foghorn voice, "Mama, isn't it strange that Miriam is completely square?" Or maybe she had in mind one sunny afternoon when he received a nervous visitor to Tring Park while "swinging unselfconsciously in a hammock, 22 stone in weight and stark naked."

Flouting generations of Rothschild tradition, Walter (1868-1937) was inept with money. To the deep dismay of his father, who had hoped that he would follow him as head of the British wing of the family's banking empire, Walter loathed everything to do with finance. He dutifully showed up to work for 18 years. But all concerned recognized it as a hopeless cause. Among other missteps, Walter allowed himself to be blackmailed to the point of financial ruin by one of his many mistresses.

Dealing with the messy business of life caused him so much angst that for one two-year period, until his family found him out, he simply dumped his personal correspondence unopened into a series of five-foot-tall wicker laundry baskets, which he then rammed shut with an iron bar, padlocked, and stacked up in a corner of his room. Miriam described his life aptly as "a series of flying leaps from one sort of frying pan into yet another fire."

And yet Walter was a genius at one thing—the business of seeking species. At the age of 20, in his first year at university, he had already accumulated 46,000 specimens, mostly birds, butterflies, and moths. (Being born into a fortune clearly helped.) That same year, he sent out his first collecting expedition, to New Zealand and Hawaii. By 21, he had his own public museum at Tring (now a unit of the Natural History Museum in London), and in the first year alone 30,000 people showed up to see it. He went on, according to Miriam, to amass "the greatest collection of animals ever assembled by one man, ranging from starfish to gorillas. It included 2.3 million set--that is, pinned--butterflies and moths, 300,000 bird skins, 144 giant tortoises, 200,000 birds' eggs and 30,000 relevant scientific books.” He, and the two collaborators he had selected as assistants, described, among them, 5000 new species and published over 1200 books and papers based on the collections.

Walter managed his natural history enterprises with a keen attention to detail and, in Miriam's phrase, "a streak of egotistical ruthlessness." For much of his adult life, he kept 400 collectors actively working in all corners of the Earth. A map showing their whereabouts looked, to one visitor at Tring, like "the world with a severe attack of measles."

This was at a moment of transition away from bold solo explorers like Alfred Russel Wallace to big biological surveys, with a new breed of collectors taking a more methodical approach to the habitats they studied. In place of spectacular novelties, historian Robert E. Kohler writes, "Survey expeditions produced vast public collections, in the millions of specimens, all prepared and arranged according to standardized procedures," or at least that was the aim.

The new species seekers meant to write monographs, not adventure stories. They wanted to have complete material for careful revisions of entire taxonomic groups, shifting species around based on better evidence and more advanced ideas about how different animals might be related. This industrial-scale natural history made for better science. It was more professional. But, except where Walter Rothschild was concerned, it could also at times seem just a little dull. In truth, naturalists now sometimes cultivated dullness, to separate themselves from the colorful amateurs who had preceded them. They wanted to be scientists, not showmen.

Bashing amateurs soon also became a way to reinforce the status of this new professional elite. In the 1870s, Yorkshire alone had 33 different natural history field clubs for enthusiastic amateur naturalists. But one scientist—a new word just coming into common use—thought it important to denounce these clubs for "unintelligent collecting" and recreation "of an instructive but by no means profound kind." Being profound was evidently a job for professionals. The scientist was constructing an academic identity, historian Samuel J.M.M. Alberti writes, by contrasting himself with "a particular type of amateur straw man, the bumbling myopic list-maker, exhibiting a 'sordid craving' for selfish collecting, with no concern for any practices or techniques beyond capture and recording."

To these insecure professionals, Walter Rothschild must have seemed like the worst sort of nightmare, not just an amateur naturalist, but a highly opinionated one, with enough money to dance rings around them, and plenty of "sordid cravings" to boot. Though he was serious about his taxonomy, Walter also wanted to wow the public and himself, not necessarily in that order. Big was good; bigger, better.

"Walter Rothschild's ambitions were always aroused by large numbers and by objects of gigantic size, difficult and costly to obtain, on the eve of extinction or entirely extinct," one acquaintance recalled. His museum displayed the largest gorilla specimen known, the first white rhino ever captured, and a huge sea elephant 18 feet long and weighing 4 tons at death. Numbers always mattered. "One of Walter's truly peculiar traits," Miriam Rothschild wrote, "was his meticulous recording in his letters of the number of specimens he had acquired and a list of the birds he had seen during his walks... He was like a schoolboy recording the runs he had scored in house matches." In his own mind, he was always competing, even against the great collectors of earlier eras. After an expedition to La Grave, in the French Alps, he noted that his party had collected more than 5000 Lepidoptera specimens in 13 days, which he deemed "a record anywhere as Wallace's collections during his Malay Archipelago trip of several years was not 6000." Miriam commented, with a sigh, '"Walter liked record bags. He never quite grew up."

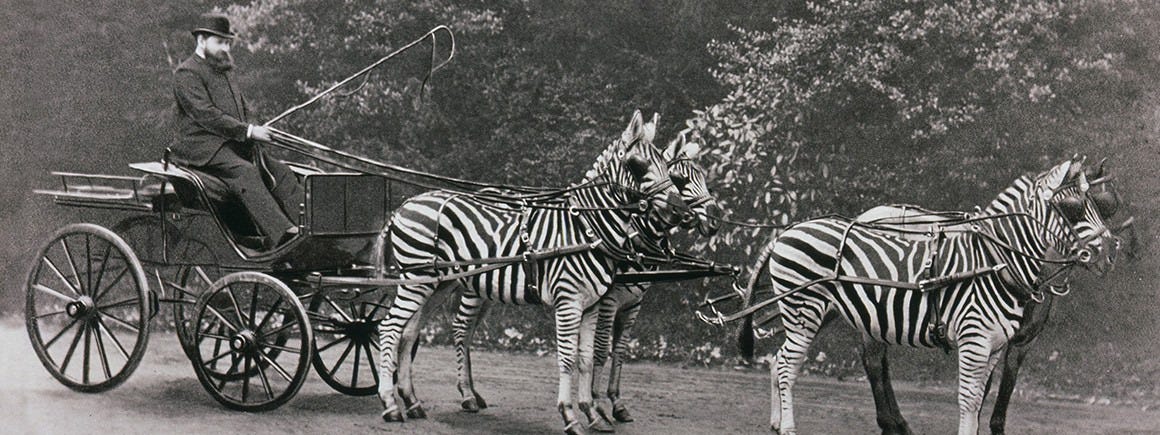

When a shipment of live zebras arrived at Tring in 1894, he set out to train them as carriage animals. Zebras are headstrong, temperamental creatures. But so was Walter Rothschild. Since they would not otherwise submit, he devised a way to lasso them by dropping their harnesses over their heads from the stable ceiling. Then he trained them singly on a small trap, before moving them up to teamwork. A few months later, he thrilled London by driving a four-in-hand with three zebras and, for steadiness, one conventional carriage pony down Piccadilly and into the forecourt of Buckingham Palace. Later, he had his photograph taken dressed in a top hat riding a giant tortoise around the garden at Tring Park

For insecure professionals, the worst thing about Walter Rothschild may have been that his amateur science was at least as good as their professional work, and often better. He had managed to complete only two lackluster years at Cambridge University, where he arrived with a flock of kiwis in tow. But from early childhood he had focused his attention on the animal world, filling up his "freakishly retentive" memory with everything he saw or read along the way. Once, much later in life, a visitor mentioned a rare New Guinea bird not in the Tring collection. Walter remarked, "That bird is illustrated on plate 87 of Gould's Birds of New Guinea," and it was.

To outsiders, and particularly to professional rivals who could not hopeto match his efforts, Walter's style of collecting must have seemed megalomaniacal, as if he meant to sweep up everything on earth. At one point, when ships visiting over the previous five years had taken and eaten 80 percent of the giant tortoise species on Duncan Island (now Isla Pinzón) in the Galapagos, he ordered his team to remove all 29 known urvivors "to save them for science" back at Tring. Rothschild meant to keep them alive, along with 30 giant tortoises from other Galapagos Islands. "I think 60 living Galapagos tortoises will make people stare,"he wrote. (Happily, enough tortoises survived in the wild to provide the stock for a captive rearing program begun in 1965, with the result that roughly 350 tortoises now live on Pinzón. Rothschild's conservation efforts were more successful where he leased entire islands to protect wildlife on site—notably on Aldabra in the Indian Ocean.)

Other times, particularly with severely threatened island birds, Walter's idea of "saving species for science" meant only saving their skins in the collection drawers at Tring. "He has therefore been accused of hastening certain species into extinction," Barbara and Richard Mearns write in The Bird Collectors. "If these species had lasted a little longer perhaps some sort of captive-breeding programme could have rescued them, but perhaps not." Early on, Alfred Newton, a professor of his at Cambridge, warned Walter against overcollecting. "I can't agree with you in thinking that Zoology is best advanced by collectors of the kind you employ," he wrote. "No doubt they answer admirably the purpose of stocking a Museum; but they unstock the world-and that is a terrible consideration."

Visitors to Tring often worked up the nerve to wonder whether he didn't have an awful lot of the same kind of bird or butterfly. But Walter always replied, "I have no duplicates in my collection." What he meant was that understanding evolution meant knowing how different populations of a species vary from one place to another, or over a period of time. It would be absurd to expect one male and one female specimen to tell the whole story. Walter wanted a long series of specimens including all possible variations—the different wing patterns or colors or beak sizes that occur in separate populations or in different age groups, the hybrids, the albinos, the individuals with mixed male and female characteristics, even the teratological specimens—that is, the monsters. To his German assistant Ernst Hartert, his characteristic cry of unmitigated delight on unpacking the latest collection to arrive at Tring was "Hartert! Hartert! Schauen sie, Schauen sie... COME AND SEE WHAT WE'VE GOT!"

Walter sometimes got too caught up in the minor variations. With cassowaries, big flightless birds from northern Australia and Papua New Guinea, he mistakenly proposed new species, according to Miriam, mainly because he was "bewitched by their multi-coloured wattles which proved in the long run rather capricious characters." But his photographic memory for the differences among specimens could also be of value in sorting out whether a species was really new. At one point, Walter dashed off a characteristically peremptory note to Hartert: "Please at once take one of the supposed new Petrels from the Galapagos Isles and relax the feet and legs and open the toes and make a note if the inside webs between the toes are yellow. I suddenly remembered either Beck or Harris in their diaries saying something about yellow webs. If this is so it is Wilson's petrel Oceanites oceanicus or Oceanites gracilis."

In addition to his extraordinary memory, Walter also had a remarkably keen eye, a search image, for whatever species interested him, wherever it happened to turn up. Once driving across Hyde Park in the middle of London, he spotted a woman climbing into her car as her chauffeur cradled a rug in his arms to place over her legs. "Stop! Stop, Christopher!" Walter yelped to his own driver, "that rug is made out of the pelts of Tree Kangaroos," the topic of his current research. The woman went off colder but £30 richer, and the rug went to the Tring Museum.

His enthusiasm for anything to do with the animal world was highly contagious, and it motivated his collectors to travel in far more perilous regions and often pay a much higher price. Most of them seem to have been built on the heroic but understated model of Albert Stewart Meek. His autobiography carried the colorful title A Naturalist in Cannibal Land but mostly bore out Walter's assessment: "Meek is a man who faces a danger bravely and then forgets all about it."

Among many other episodes, he worked with local hunters in Papua New Guinea who brought him butterflies collected with nets made of spider webs, or shot down with bow and arrow. One such find was the largest butterfly in the world, the Queen Alexandra's Birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae), with a 10-inch wingspan. To satisfy Tring's appetite for a complete series, Meek also found the pupae and bred up perfect specimens in captivity.

All of Walter's collectors routinely risked danger, suffering, and death. One collector wrote home poignantly about his solitary Christmas celebration in Gabon: "I was busy all day collecting butterflies which are now at Tring. I returned to my hut dead-tired & weary & feeling ill. I could not eat but made a feeble effort to swallow a mouthful of the small plum-pudding (a shilling tin which I had brought out with me from England 8 months previously). I felt fever coming on & went to bed, carefully blowing out my half-penny candle as candles are unobtainable ... Then the fever took me, the shivering fit shaking my teeth & bones. I was delirious & moaned till dawn when the merciful perspiration broke out & the fever was broken, but it left me as weak as weak can be. That was my last Xmas 1907! How & where I shall spend this one, God alone knows." In Papua New Guinea, another Tring collector was less fortunate. For three nights, he ranted deliriously about seeing "motor cars, railway trains, children riding on clouds and the like," then died suddenly of "malarial fever and sleeplessness." The victim went unnamed in Meek's account, one of innumerable other collectors and assistants who died in the search for species.

This death, quickly passed over in the recounting, serves as a reminder of the subtext to all the overcrowded display cases at Tring ("I want to prove that one can put in one case 3 times as much as is usually done and yet see all well," Walter declared). It is the subtext to those endless drawers of carefully arranged specimens in museums around the world: Someone had collected each specimen; killed it; skinned it; stuffed it, set it, or put it in preservative; pencil-scratched a label for it; carried it cross-country; shipped it home; studied it; and classified it, and then repeated this ritual over and over, countless millions of times.

For each specimen, someone had gone hungry and sleepless. Someone alone in a remote and hostile territory had wept. Someone had perhaps drowned, been murdered, suffered malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, or typhus. Someone had certainly cursed and complained, though not so much as we might expect. Someone had said, "Hunh!" And someone had rejoiced. When a local assistant brought him a spectacular new butterfly species, Ornithoptera chimaera, Meek rewarded him extravagantly with two shillings, two tins of English bacon, and five sticks of tobacco. "I felt more pleased than if I had been left a fortune," he wrote. "A fine discovery of that sort stirs the heart of a collector. He forgets hardships and troubles, and remembers only that he has given something to science, taken from Nature one of her secrets. 'A little secret!' some may say, but naturalists do not think so."

Later naturalists would place high value on the work Walter Rothschild, his curators Hartert and Karl Jordan, and their many collectors had done in putting together those lengthy series of specimens for each species. When a later ornithologist, David Lack, was working out how speciation had occurred in Darwin's finches, he had to spend months doing fieldwork in the Galapagos. But fieldwork wasn't enough. "You've just got to come back to the Rothschild collection and get down to measuring beaks," he wrote. He also noted that "The drawers of the Rothschild cabinet contain more representatives of some of the Hawaiian sicklebills than are alive in the Islands today."

Though Rothschild and his collectors were only dimly aware of how important genetics would become to the study of nature, their work preserved the broadest possible swath of genetic variation for each species. "It is only against the panorama of modern research that the full value of Walter's butterflies becomes apparent," Miriam Rothschild wrote.

"Its importance lies in the unfolding and presentation before your eyes of a whole order in all its variety and complexity, culled from continent to continent, from one far flung oceanic island to another, from desert and forest and prairie and mountain range. There is also an indefinable factor about these collections, a Walterian factor—call it what you will—a whiff of zest and wonder, which must somehow have been pinned in among the butterflies. Suddenly the outlook broadens, the horizon expands, a penny drops, new ideas materialize, the mind 'takes off.’"

But a different Walterian factor shaped the eventual fate of the collection at Tring. In 1931, Walter's financial missteps caught up with him, possibly aggravated by his persistent blackmailer. (She was a "charming, witty" aristocrat, according to Miriam, who never revealed her identity.) With his characteristic secretiveness, Walter discussed his situation with no one. Instead, he made a sort of "Sophie's Choice" among his beloved children, and privately offered the bird collection, minus the cassowaries and a few other sentimental favorites, to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney made a gift to cover the $225,000 cost—less than a dollar apiece for specimens said at the time to have cost Walter altogether $1 million. The Rothschild family heard about the transaction first in the newspapers. At the Berlin Museum, to which Hartert had by then retired, a colleague recalled how he got the news: "‘My collection! My collection!' he stammered out, his chest heaving and his clear eyes swimming with tears." Hartert died a year-and-a-half later, Walter Rothschild a few years after that, at age 69.

In her biography, Miriam Rothschild noted that Walter's portrait does not hang in the family bank and that "all traces of his activities have been expunged from the archives." But she added that, long after the family's many bankers have faded into pin-striped oblivion, Walter Rothschild will live on in "the giraffe, the bird of paradise, the scarlet climbing lily, the blue/mauve orchid, the silk moth with the mother-of-pearl 'windows' in its wings and the blind white intestinal worm," among scores of other new species that scientists have named in his honor.

Richard Conniff’s latest book, Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion, is now out in paperback. His other books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

OTHER READING

Johnson, Kirk Wallace, The Feather Thief, is about a brazen robbery at Tring to sell the prized bird feathers for high-end fly-tying.

Kohler, Robert E., All Creatures: Naturalists, Collectors, and Biodiversity, 1850-1950

Mearns, Barbara and Richard, The Bird Collectors

Rothschild, Miriam, Dear Lord Rothschild: Birds, Butterflies, and History

Yet another contributor to our understanding of biodiversity that I had not known of. Thanks!

What a guy! Thanks, Dick.