Want To Save This Cute Species? Go Visit.

Modeled on birding life lists, primate life-listing can prevent extinctions.

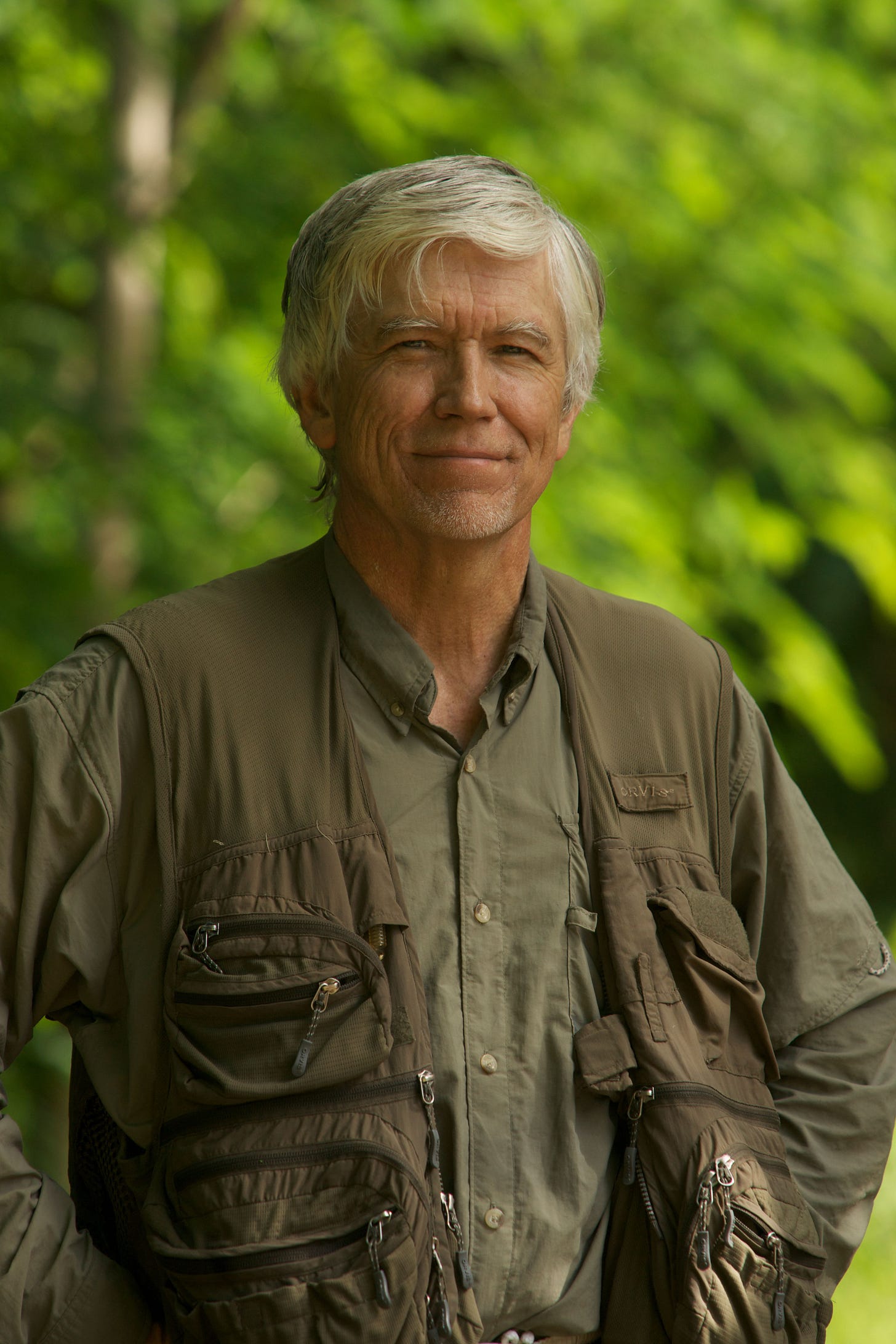

by Richard Conniff

More than 60 percent of primate species—our cousins the apes, monkeys, and prosimians—are endangered or critically endangered, and 75 percent are in decline. So when leading conservationists recently put out their red alert for our 25 most endangered primates, it reminded me that there is one big thing people can do to help save species and rebuild populations: Go see them, and spend a little money in the nearby community.

“You take one tour to a place that's never had a tour before,” says Re:Wild’s Russ Mittermeier who launched the idea of primate ecotourism just over 20 years ago, “and you pay to see a primate, and all of a sudden people go, ‘Oh, so these crazy people are coming to see our animals.’” They’re surprised that you don't have primates like theirs where you live—and even more surprised that species they regard as part of ordinary life exist no place else on Earth. That, says Mittermeier, starts them thinking.

What follows is my account of one primate ecotourism trip in Madagascar, and then a brief how to (and where to) for getting started on your own primate life list. It’s definitely not just about seeing mountain gorillas in the Virunga mountains.

One weekend in 2006, when I happened to be Madagascar on another story, I got word that Russ Mittermeier, then president of Conservation International, was visiting not too far away. I arranged to meet him in the dusty town of Farafangana, on the southeast coast of Madagascar. His official goal was to build ecotourism in what is variously known as “the eighth continent” and “the twelfth-poorest nation on earth.”

Mainly, though, Mittermeier was in Farafangana to bag two new lemurs to add to his already vast primate life list. Science then recognized 650 species or subspecies of apes, monkeys, and prosimians (the last of these including lemurs, lorises, and bush babies). Mittermeier himself had by then seen more than half of them in the wild, possibly more than anyone ever. Among other things, he has sat nearby, wondering whether to avert his eyes, while mountain gorillas had sex. He has also stood watching nervously while chimpanzees ripped a live colobus monkey to shreds. Once, at a bai, or forest clearing, in the Republic of Congo, Mittermeier was watching lowland gorillas, when the gorillas sidled off, circled around, and sat down 30 feet behind, hidden by foliage, to watch him. Maybe it was the start of a different sort of life list: Russ Mittermeier, Homo sapiens. Check.

This trip to a couple of remnant scraps of forest 18 miles outside Farafangana was aimed at adding to his list one new species, the white-collared brown lemur, and one new subspecies, the southernmost variety of the black-and-white ruffed lemur.

Mittermeier, then 57, was dressed for the hunt in sneakers, white socks, shorts (“I like to see the leeches,” he said), a khaki shirt, a web vest, and a baseball cap, turned backward for better visibility while thrashing through the underbrush. Leitz 10 x 40 binoculars hung from his neck, beside a Nikon digital camera with a 400-millimeter vibration-reducing telephoto lens. At his belt was a Brazilian machete in a duct-taped sheath, and a Nalgene water bottle containing the murky leavings of miscellaneous Cokes and Oranginas, diluted with water. (On a tour when the animated film Madagascar was in production, Dreamworks mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg professed horror at the “disgusting water bottle.” But Mittermeier was unabashed: “I don’t like to waste things.”)

Up to that point, life-listing had been largely an ornithological obsession, with birders trekking to the far ends of the earth to add some obscure feathered find to their lists. Mittermeier’s 21-year-old son, John, for instance, had already checked off 4,000 bird species, which made his list substantially larger than his father’s. “There are millions of websites for birders, and it’s a multibillion-dollar industry,” said Mittermeier. “So why not primates?”

He was promoting primate life-listing at least in part for the sheer joy of counting coup. Status competition is an important behavioral phenomenon in most primate groups, including, notably, the Mittermeier family. Among other things, everybody in the family keeps track of countries and “country-like entities” visited; they exchange cryptic e-mails: “37” or “49.” Mittermeier said there is not much his eldest son can’t beat him at these days (“I used to have chin-ups on him”), but “he doesn’t have my country list,” which at that point stood at 114. There was a corresponding, though less celebrated, list of exotic diseases: “I’ve had leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, pin worms, hookworms, everything else,” he aid. “No malaria. Lucky.”

But apart from hardship, and the thrill of one-upmanship, what’s the appeal of primate life-listing for other travelers? Lemurs in particular swing through the treetops and pirouette along the ground more gracefully than any human ballet dancer. Primates also catch and hold the attention with behaviors that are a tantalizing mix of the deeply familiar and the foreign. And they are colorful, more so in some cases than birds. The British naturalist Gerald Durrell once encountered a mandrill in full sexual display, its bottom like “a newly painted and violently patriotic lavatory seat,” all blue on the outer rim and “virulent sunset scarlet” within. “Wonderful animal, ma’am,” Durrell said to his guest, Her Royal Highness Princess Anne. Then he added, “Wouldn’t you like to have a behind like that?”

Mittermeier was also promoting primate life-listing with the idea that it would be good for the primates, by bringing ecotourism dollars to local people who might otherwise value forests only for fuel and building material, and creatures like lemurs solely for meat. Madagascar, 250 miles off the east coast of Africa, was then getting about 180,000 visitors a year, far fewer than even its tiny neighbor, the Seychelles. But Mittermeier was hoping his idea would change that, and at the same time prevent lemurs and other primates from becoming extinct.

Madagascar is the only place on earth where lemurs live, and they are adorable, mostly small, often brightly colored, with round, bewildered eyes (blue, in one species). “The best are Propithecus candidus [silky sifakas],” said Mittermeier. “They’re big and fluffy with a pink nose, and you think, ‘This isn’t a real animal. It’s a Disney creation.’” On the other hand, the aye-aye, Daubentonia madagascariensis, looks like something out of Stephen King. Lemurs are extraordinarily varied, with about 100 species and subspecies on an island the size of Texas. Because of extensive deforestation, they actually survive in an area Mittermeier described as more like “three New Jerseys.” In some protected areas, it’s possible, with a little hiking, to see 10 different species. Visit five or six sites, and you can get 25 species in a trip.

So is the notion of primate life-listing practical? “There’s an obvious reason to be skeptical,” said John Mitani, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Michigan, who studies chimpanzees in Uganda. “Unlike bird listing, it’s not something you can do in your backyard.” The United States has more than 900 wild bird species anybody can get started on. Birdwatchers can also buy field guides, bird feeders, birdsong apps, and video nest cams to sustain their passion year-round. In fact, they spend more than $100 billion a year on the stuff. (That’s the 2022 figure just for U.S. birders.)

There’s no equivalent for watching primates, unless you count eavesdropping on your human neighbors. Baboons and gray-cheeked mangabeys don’t, as a rule, turn up in our backyards. So the only way for beginners to get started is to travel. “Here you’re talking about something that appeals only to people who have money,” said Mitani. Then it dawned on him: “It could be good to have people with money interested in this.”

At the Manombo Reserve outside Farafangana, our hunt took place in French, English, and Malagasy, with Mittermeier’s host, biologist Jonah Ratsimbazafy, pausing now and then to cry out, “Any ve ny biby?”—“Have you found the animal?”—to various local guides. Ratsimbazafy also tried speaking to the lemurs in their own language, a back-of-the-throat, gup-gup-gup sound. Finally, one of the guides said,“Aty!” or “There it is!”

The white-collared brown lemur, Eulemur fulvus albocollaris, sat on a branch 30 feet above the trail, serene as a cat, with its long fluffy tail folded over one arm. It had big, tawny, muttonchop cheeks, and its hazel eyes glowed in the afternoon sun. It gazed down curiously as Mittermeier crept underneath for one more close-up, and then another and another and another.

Mittermeier needed the perfect picture, he said, for a new edition of the guidebook he co-authored, The Lemurs of Madagascar. He was also working on a series of pocket field guides, so future primate life-listers will know what to look for and where. A half-hour later the lemur was still there, the sort of trusting behavior that often leads biologists to regard them as not too bright. “They’re not chimpanzees,” said Mittermeier. “They’re not even capuchins.”

Next day Mittermeier was back, accompanied by a top official from the regional government, to look for the somewhat more skittish black-and-white ruffed lemur, Varecia variegata variegata. At a rickety log bridge a big Mercedes truck was stuck up to its hubcaps, with a load of freshly cut trees from the reserve in the back.

“It’s illegal,” said Ratsimbazafy. “But nobody cares out here in the remote forest.”

“Except for today,” said Mittermeier, as the regional official ordered the driver to report with his boss to the gendarmerie.

In the forest, the black-and-white ruffed lemur soon turned up walking on a branch overhead, looking like a small, arboreal panda. Mittermeier held up a tape recorder and played the call of another lemur, the indri, a high-pitched sound like air being slowly let out of a balloon. No reaction. But the chucking and squealing of other black-and-white ruffed lemurs caused the animal to look up sharply, cocking its head one way and then the other to locate the sound.

“He’s coming, he’s coming to fight! Look!” said Mittermeier.

The lemur leapt into the tree directly overhead, considered the possibilities for a moment, then moved off again. “He’s chicken!” said Mittermeier, disappointed.

“He may have been feeling alone,” said Ratsimbazafy.

On the walk back out of the forest, Mittermeier and the regional official talked about the potential of primate life-listing. “This is really a ticker thing to come here and get a black-and-white ruffed lemur and a white-collared brown lemur,” Mittermeier said. “There are eight critically endangered primates in Madagascar, and we knocked off two of them here.” The latter in particular exists nowhere else on earth. The regional official, an economist with a corporate background, seemed to agree, though he worried that Farafangana was too far off the usual tourist circuit.

“Improve the road, that bridge mainly,” said Mittermeier. “Clean up the trails, so you’re following the route of the animals. You could do it in two weeks with a few guys. C’est très facile.” Conservation International would put up the money, he said.

“Each of these animals in the forest is worth a fortune to the region. If you eat it, you get a meal for one day. If you keep it in the forest, people will keep coming and coming to see it.”

Later, flying out of Farafangana in a chartered Cessna 172, Mittermeier circled over the patches of forest he had just visited, dwindling remnants in the vast landscape of deforestation. But it was his nature to be optimistic: “You come to a place like this, meet the No. 2 in the regional government and the big businessman, and soon people are saying, ‘The vazaha came, the foreigners, and talked about how important the lemurs are.’ And all of a sudden attitudes start to change.”

The plane circled over Manombo and the other patch of forest he had visited, just across the road. Below, columns of smoke rose here and there where farmers continued to nibble at the forest. “This is basically it,” said Mittermeier. “These two properties are the future for these animals.”

UPDATE: Manombo is regrettably still too far off the usual tourist circuit. But Mittermeier estimates that there are now 50 ot 60 sites specializing in lemur tourism in other parts of Madagascar, up from zero when he first visited in the early 1980s. Tourism there, largely for lemurs, has also soared. Worldwide, several hundred sites focus on primates, but with odd gaps. Brazil, for instance, has more primates than any other country, with 155 species and subspecies, but except for a few established sites, primate watching is just getting started there, according to Brazilian primatologist Leandro Jerusalinsky.

WHERE TO SEE THEM

The count for primate species and subspecies in the world is now up to 721, including 104 newly described since 2000. About 70 percent of them live in just four countries—Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia, and the Republic of Congo. But primates (other than humans) also live in 88 other countries, in Asia, South and Central America, and Africa.

To help primate-watchers make sense of this diversity, Mittermeier and his co-authors produce laminated pocket guidebooks for different regions (see photo above). You can browse the available titles from Re: Wild here and find others from Conservation International at this British website.

A few rules apply: Hire a local guide, not just to boost the economy but because they’re the one’s who can find what you’re looking for. When you find the animals, keep a reasonable distance. Don’t touch or feed them. Trying to get a selfie of one sitting on your shoulder is strongly discouraged.

Bear in mind that many of the best places for primate viewing are still poorly developed. “These places are wild,” says Amy Vedder, a wildlife biologist who helped launch mountain gorilla ecotourism in Rwanda. “You’re there on nature’s terms. You’re not guaranteed a viewing in most of these places. It’s still an adventure, which is I think the great part.”

But it’s also possible to see some primates even in the middle of cities commonly visited by business travelers. Raffles’ banded langur, for instance, is critically endangered but still survives in a park in the middle of Singapore. The pied tamarin, also critically endangered, hangs on in the city of Manaus, the main starting point for visits to the Brazilian Amazon.

So where to begin? These are some of the world’s primate-watching hot spots recommended by Mittermeier, Vedder, Jerusalinsky, and other primatologists.

Africa

Parc National des Volcans (PNV) in Rwanda is still the top spot to see mountain gorillas. The park issues just 80 viewing permits a day, at $1500 each. Primate watchers can also track the endangered golden monkey.

From PNV, it’s about a five-hour drive to Rwanda’s Nyungwe National Park. There the walking trails run along hillside contours and, in places, enable hikers to look directly across into upper forest canopy. Black-and-white colobus monkeys travel through in groups of 300 or 400 animals. “It’s incredible!” says Vedder. There are also habituated groups of blue monkeys, gray-cheeked mangabeys, and chimpanzees. Nyungwe is also home to the l’Hoest’s monkey, the golden monkey, the owl-faced monkey, and the vervet monkey.

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, across the border in Uganda, is a less expensive but somewhat less scenic site for viewing mountain gorillas, and Kibale National Park nearby offers some of the best viewing in Africa for chimpanzees and a dozen other primates.

In Gabon’s Lopé National Park, you can see the largest gatherings of nonhuman primates in the world—groups of up to 1,000 mandrills at a time. Lopé has black colobus monkeys, western lowland gorillas, chimpanzees, mangabeys, and the endemic sun-tailed monkey, plus an abundance of elephants, leopards, red river hogs, and (if you insist) 412 bird species. Ivindo National Park, five hours away by car, is another good place to see western lowland gorillas and elephants mingle at the Langoue Bai, a natural clearing in the forest.

On the border where the Republic of Congo, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic meet, the Goualougo Triangle—described by Time magazine as “the last Eden”—has western lowland gorillas and chimpanzees. It’s adjacent to Congo’s Nouabale-Ndoki National Park.

In Madagascar, three hours from the capital Antananarivo (“Tana” for short), Parc National de Mantadia-Andasibe boasts “the biggest and most attractive lemurs habituated,” says Mittermeier, including groups of indri, diademed sifakas, and black-and-white ruffed lemurs, along with nine other lemur species. “You should get at least seven or eight if you spend three days there.”

Ranomafana National Park, in the southeastern rainforest, has about 20 lemur species. Because researchers have been studying them for decades, many are tolerant of visitors and, with the help of local guides and a little hiking, easy to see close-up. The mouse lemur, the smallest primate in the world, will come out at night for pieces of banana.

South America

Manu National Park is located northeast of Cuzco, where every visitor to Peru goes to see the archaeological ruins of Machu Picchu. It can take two or three days to get there, but “the density of wildlife is just amazing,” says Charles H. Janson, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Montana. You can count on seeing eight species of primates, including capuchins, squirrel monkeys, howler monkeys, titi monkeys, spider monkeys, and the emperor tamarin, which has an impressive Fu Manchu mustache. Five other primate species are less common, but they include the Goeldi’s monkey and the pygmy marmoset. Two 100-foot-tall platforms make canopy-level viewing possible. (Among other things, it’s a good way to avoid getting peed on by howler monkeys.) Only a few thousand visitors make the trip to Manu each year, says Janson, but that’s still “a big blip in the local economy.”

In Brazil, two hours’ drive from Rio de Janeiro, the Poço das Antas Biological Reserve represents one of the last surviving remnants of the Atlantic coastal rainforest, and it’s the site of one of the most successful primate reintroduction programs to date. Golden lion tamarins, bred at zoos around the world, now thrive there. The conservation movement has also spread to neighboring farms, which serve as halfway houses for captive-bred animals on their way back to the wild, and as private ecotourism reserves.

Also in Brazil, Vedder recommends the Mamiraua Ecological Station, a day trip by boat upriver from Manaus. From the Uakari Floating Lodge there, visitors do their primate watching by canoe. “It’s such a kick to be in a canoe in a flooded forest 11 to 15 meters [roughly 36 to 50 feet] above land,” she says. “You are canoeing in the lower part of the canopy,” almost eyeball-to-eyeball with primates, including the endangered uakari.

Asia

Russ Mittermeier describes the Mentawai Islands off the west coast of Sumatra as “the Galápagos of Indonesia,” with seven primates found nowhere else in the world, including an endemic primate genus. “I got four of the species, including the endemic genus, in two days.” But the locals spend much of their free time hunting monkeys, so they can be skittish. The island’s Siberut National Park a 12-hour boat ride from Padang in West Sumatra.

In Sabah, in northern Borneo, about 80 orangutans, mostly orphaned by poaching, now wander freely in the forest at the Kabili Sepilok Forest Reserve. It’s also a good spot to see proboscis monkeys. A few hours away, in the lower Kinabatangan floodplain, around the village of Sukau, visitors can track wild orangutans, proboscis monkeys, and Bornean gibbons with the help of Red Ape Encounters, a local organization that also arranges home stays for visitors interested in Malay culture. In Sabah, in northeastern Borneo, the Danum Valley is home to gibbons, orangutans, red leaf monkeys, and an abundance of other wildlife.

There are many other options. Mittermeier, whose primate life list is now well over 400 species and subspecies, including at least one representative of all 83 primate genera, rattles off the possibilities by email: Try the endangered northern muriqui and the spider monkeys at Feliciano Miguel Abdala Private Natural Heritage Reserve near Caratinga in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. Visit the chimpanzees and colobus monkeys at Tai Forest in Cote d’Ivoire. Go see the rare Iringa red colobus and the Sanje crested mangabey at Udzungwa Mountains National Park in Tanzania.

Just go. For the mountain gorillas, the golden lion tamarins, Madagascar’s lemurs, and many other species in danger of extinction, primate watching has become a lifeline to the future.

I was just thinking about my first non-human primate. I was in bed on Barro Colorado Island in Panama's Lake Gatun. Suddenly an appalling, apocalyptic noise broke out. It was like waking up on the track in the middle of a drag race. Or hearing an asteroid plummeting down on the Planet Earth. Or, what I actually thought, in deep terror, it was the new American president, Ronald Reagan, letting loose the cruise missiles, target unknown. Later, I learned that it was just howler monkeys doing the thing that gave them their name ... If you have had an interesting first (or favorite) primate encounter, please tell me about it in a comment.

My first encounter with primates in the wild was a male Howler at Catemaco, Mexico. I was 16 on the trip that kindled my lifetime passion for rainforests. That passion led me to decades in the world’s third largest remaining rainforest-- New Guinea. Ironically, there are no primates in the New Guinea forests, they do not cross Wallace’s Line.

But much more profound for me was an experience I later had with primates on the other side of Wallace’s Line, in the north of Borneo, one that kindled my passion for conservation.

I was in a remote camp in Sabah which has, or should I better say had, the most magnificent tropical forests in the world, dominated by dipterocarps. These are magnificent, tall hardwoods with straight boles supporting a cathedral canopy so high the life there can move invisible from a puny, earthbound human observer. I was there as part of an effort to collect specimens for a museum; a desperate effort to at least document some of the life in these forests. We were in an enormous logging concession; what makes dipterocarps beautiful also makes them valuable. Uncontrolled clear cut timber pillage was in full swing across the lowlands.

We were far ahead of the logging front, driven as far as a D9 bulldozer could take us then we hiked deeper into the forest. There we built a camp and lived under the dipterocarp ceiling far above where several species of primates lived.

The haunting calls of gibbons would ring through the morning air, calling across valleys. Their calls are so mystical you sometimes hear them dubbed into movies—they were the sound of the Forest Moon of Endor, where the Ewoks lived (if you are a Star Wars fan). They could sit concealed for hours, only revealed when they gracefully moved, brachiating from limb to limb with their long muscular arms. Sometimes I would see one launch from the top of one tree across a huge gap to catch a limb maybe 50 feet or more away. They would use the spring of the take off branch to help launch and the bending of the landing branch to absorb the momentum. Only to use that rebound to throw the gibbon onward. Seeing this is a wondrous moment of grace, speed, and agility. Seeing this made all the day’s land leeches, stings, bites and relentless itching worthwhile.

But one moment stands out, not just among all my encounters with gibbons, but among all my encounters with rainforest primates. After six weeks in one camp, the chainsaws were getting closer. The sound of a tree dropping was dreadful—the canopy whooshed on the way down, like one last giant exhalation. The crash sends a pressure wave had that resembled the sensation of banging your head on a low beam, only longer.. After one particularly close giant fell, I witnessed a gibbon fleeing. It was clearly in a hurry heading even deeper into the doomed forest. After leaping a void, rather than launching onwards, it paused. Through my binoculars I could see her clearly; looking right into my soul. A second pair of sad eyes peered from the infant clinging to her chest. They just stared at me a long time. They seemed to be asking me “why?” as I wondered the same thing.

https://open.substack.com/pub/andrewmack2/p/primate-encounters?r=nia4b&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true