Why Did God Make Houseflies? (Part 2)

Meeting Dr. Housefly & the day of the Swat-the-Fly Campaign

by Richard Conniff

Vincent Dethier, a biologist at the University of Massachusetts and author of To Know A Fly, turned out to be a gentle, deferential fellow in his mid-seventies, with weathered, finely wrinkled skin and a pair of gold-rimmed oval eyeglasses on a beak nose. He suggested mildly that my fly might not have responded because it was outraged at the treatment it received. It may also have eaten recently, Dethier continued, or it may have been groggy from hibernation. (Some flies sit out the winter in diapause, in which hormones induce inactivity in response to shortened day length. But cold, not day length, is what slows down hibernating species like the housefly, and the sudden return of warmth can start them up again. This is why a fly may miraculously take wing on a warm December afternoon in the space between my closed office window and the closed storm window outside, a phenomenon I had formerly regarded as new evidence for spontaneous generation.)

Dethier has spent a lifetime studying the fly's sense of taste, "finding out where their tongues and noses are, as it were." He explained the workings of the proboscis for me: Fly taste buds are vastly more sensitive than ours, another reason to dislike them. Dethier figured this out by taking saucers of water containing steadily decreasing concentrations of sugar. He found the smallest concentration a human tongue could taste. Then he found the smallest concentration that caused a hungry fly to flick out its proboscis. The fly, with fifteen hundred taste hairs arrayed on its feet and in and around its mouth, was ten million times more sensitive.

When the fly hits paydirt, the proboscis telescopes downward and the fleshy lobes at the tip puff out. These lips can press down tight to feed on a thin film of liquid, or they can cup themselves around a droplet. They are grooved crosswise with a series of parallel gutters, and when the fly starts pumping, the liquid gets drawn up through these gutters. The narrow zigzag openings of the gutters filter the food, so that even when it dines on excrement, the fly can "choose" some microorganisms and reject others. A drop of vomit may help dissolve the food, making it easier to lap up. Scientists have also suggested that the fly's prodigious vomiting may be a way of mixing enzymes with the food to aid digestion.

If necessary, the fly can peel its lips back out of the way and apply its mouth directly to the object of its desire. While it does not have true teeth, the mouth of the housefly is lined with a jagged, bladelike edge, which is useful for scraping. In his book Flies and Disease, Bernard Greenberg, a forensic entomologist at the University of Illinois in Chicago, writes that some blowflies (like the one on the rim of my beer glass, which turned out to be an olive green blowfly, Phormia regina) "can bring one hundred fifty teeth into action, a rather effective scarifier for the superficial inoculation of the skin, conjunctiva, or mucous membranes."

A City of No Flies?

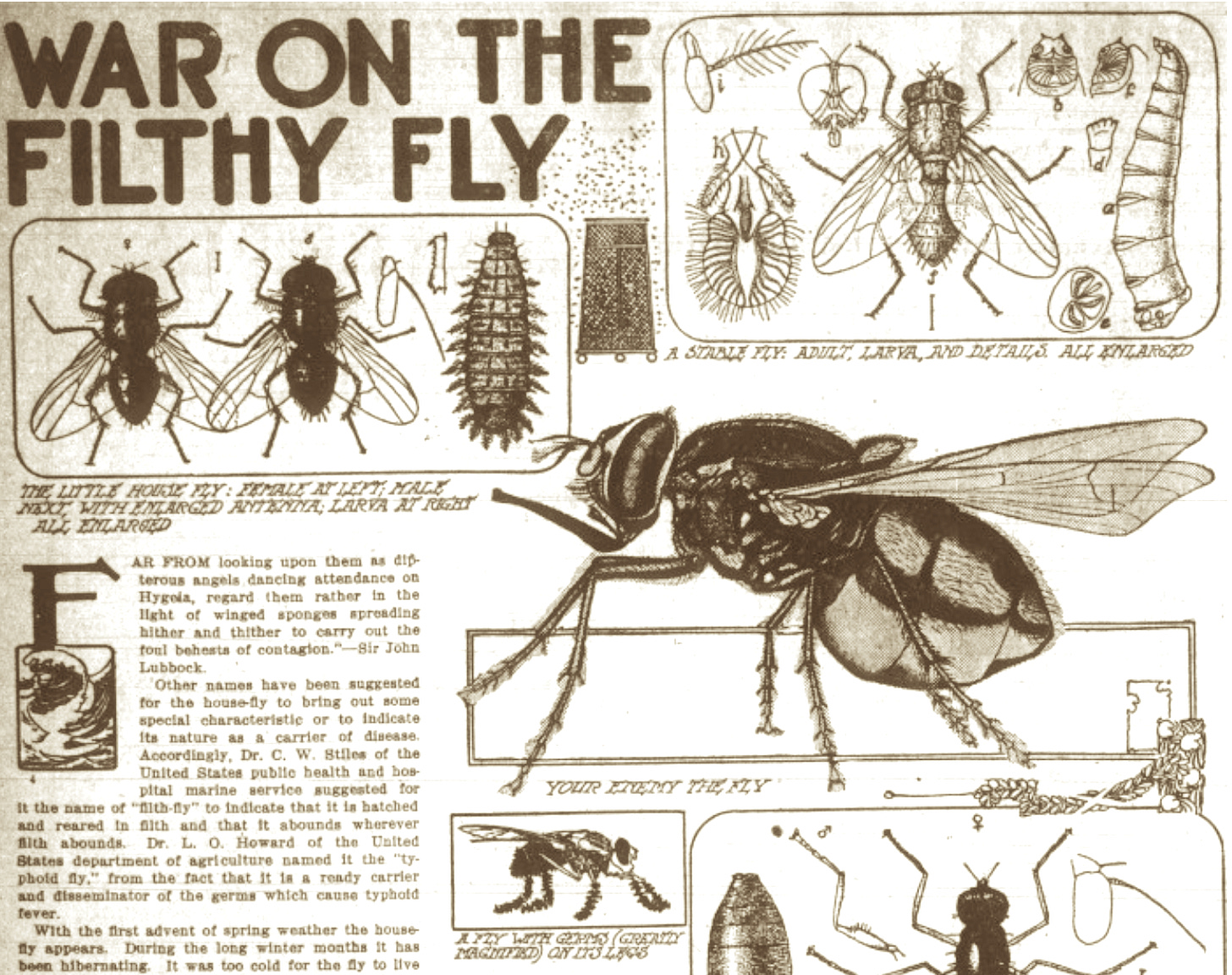

Hence the final great question about flies: What awful things are they inoculating us with when they flit across our food or land on our sleeping lips to drink our saliva? Over the years, authorities have suspected flies of spreading more than sixty diseases, from diarrhea to plague and leprosy. As recently as 1951, the leading expert on flies repeated without demurring the idea that the fly was "the most dangerous insect known," a remarkable assertion in a world that also includes mosquitoes. One entomologist tried to have the housefly renamed the "typhoid fly."

The hysteria against flies early in this century arose, with considerable help from scientists and the press, out of the combined ideas that germs cause disease and that flies carry germs. In the Spanish-American War, easily ten times as many soldiers died of disease, mostly typhoid fever, as died in battle. Flies were widely blamed, especially after a doctor observed particles of lime picked up in the latrines still clinging to the legs of flies crawling over army food. Flies were not "dipterous angels," but "winged sponges speeding hither and thither to carry out the foul behests of Contagion." North American schools started organizing "junior sanitary police" to point the finger at fly-breeding sites. Cities sponsored highly publicized "swat the fly" campaigns. In Toronto in 1912, a girl named Beatrice White killed 543,360 flies, altogether weighing 212.25 pounds, and won a $50 first prize. This is a mess of flies, 108.7 swatted for every penny in prize money, testimony to the slowness of summers then and to the remarkable agility of children—or perhaps to the overzealous imagination of contest sponsors. The figure does not include the 2.8 million dead flies submitted by losing entrants. (The "swat the fly" spirit still lives in China. In 1992, Beijing issued 200,000 flyswatters and launched a major sanitation campaign under the slogan, "Mobilize the Masses to Build a City of No Flies." Ending open-air defecation was ultimately more effective.)

But it took the pesticide DDT, developed in World War II and touted afterward as "the killer of killers," to raise the glorious prospect of "a flyless millennium." The fly had by then been enshrined in the common lore as a diabolical killer. In one of the "archy and mehitabel" poems by Don Marquis, a fly visits garbage cans and sewers to "gather up the germs of typhoid influenza and pneumonia on my feet and wings" and spread them to humanity, declaring "it is my mission to help rid the world of these wicked persons / i am a vessel of righteousness."

Public health officials were deadly serious about conquering this archfiend, and for them DDT was "a veritable godsend." They recommended that parents use wallpaper impregnated with DDT in nurseries and playrooms to protect children. Cities suffering polio epidemics frequently used airplanes to fog vast areas "in the belief that the fly factor in the spread of infantile paralysis might thus be largely eliminated." Use of DDT actually provided some damning evidence against flies, though not in connection with polio. Hidalgo County in Texas, on the Mexican border, divided its towns into two groups, and sprayed one with DDT to eliminate flies. The number of children suffering and dying from acute diarrheal infection caused by Shigella bacteria declined in the sprayed areas but remained the same in the unsprayed areas. When DDT spraying was stopped in the first group and switched to the second, the dysentery rates began to reverse. Then the flies developed resistance to DDT, a small hitch in the godsend. In state parks and vacation spots, where DDT had provided relief from the fly nuisance, people began to notice that songbirds were also disappearing.

In the end, the damning evidence was that we were contaminating our water, ourselves, and our affiliated population of flies with our own filth (not to mention DDT). Given access to human waste through inadequate plumbing or sewage treatment, flies can indeed pick up an astonishing variety of pathogens. They can also reproduce at a godawful rate; in one study, 4,042 flies hatched from a scant shovelful, one-sixth of a cubic foot, of buried night soil. But whether all those winged sponges can transmit the contaminants they pick up turns out to be a tricky question, the Hidalgo County study being one of the few clear-cut exceptions. Of polio, for instance, Bernard Greenberg writes, "there is ample evidence that human populations readily infect flies. . . . But we are woefully ignorant whether and to what extent flies return the favor."

Flies thus probably are not, as one writer declared in the throes of the hysteria, "monstrous" beings "armed with horrid mandibles . .. and dripping poison." A fly's bristling unlovely body is not, after all, a playground for microbes. Indeed, bacterial populations on the fly's exterior tend to decline quickly under the triple threat of compulsive cleaning, desiccation, and ultraviolet radiation. (Maggots actually produce a substance in their gut that kills off whole populations of bacteria, which is one reason doctors have sometimes used them to clean out infected wounds.) The fly's "microbial cargo," to use Greenberg's phrase, tends to reflect human uncleanliness. In one study, flies from a city neighborhood with poor facilities carried up to 500 million bacteria, while flies from a prim little suburb not far away yielded a maximum count of only 100,000.

But wait. While I am perfectly happy to suggest that humans are viler than we like to think, and flies less so, I do not mean to rehabilitate the fly. Any animal that kisses offal one minute and dinner the next is at the very least a social abomination. What I am coming around to is St. Augustine's idea that God created flies to punish human arrogance, and not just the calamitous technological arrogance of DDT. Flies are, as one biologist has remarked, the resurrection and the reincarnation of our own dirt, and this is surely one reason we smite them down with such ferocity. They mock our notions of personal grooming with visions of lime particles, night soil, and dog leavings. They toy with our delusions of immortality, buzzing in the ear as a memento mori. (Dr. Greenberg assures me that fly maggots can strip a human corpse roughly halfway to the bone in several weeks, if the weather is fine. Then they hand the job over to other insects.) Flies are our fate, and one way or another they will have us.

It is a pretty crummy joke on God's part, of course, but there's no point in getting pouty about it and slipping into unhealthy thoughts about nature. What I intend to do, by way of evening the score, is hang a strip of flypaper and also cultivate the local frogs and snakes, which have a voracious appetite for flies (flycatchers don't, by the way; they prefer wasps and bees). Perhaps I will get the cat interested, as a sporting proposition. Meanwhile I plan to get a fresh beer and sit back with my feet up and a tightly rolled newspaper nearby. Such are the consolations of the ecological frame of mind.

This is a hilarious piece . Congratulations Richard

:)