Why I Live Here

This valley is where I cross through the magic wallpaper

by Richard Conniff

When I was a kid my father used to tell stories about the magic wallpaper in his childhood home in The Bronx, which you could step through, if you knew the secret code, and suddenly be in quiet rural countryside.

For me, the lower Connecticut River Valley has always felt like that. It’s a pocket of small New England towns, beginning somewhere between Middletown and Haddam, Connecticut, and continuing 20 or 25 miles south to where the river empties into Long Island Sound. It’s a landscape of hills, rock-strewn woods, creeks, coves, and tidal marshes, somehow surviving almost intact in the middle of the sprawling Eastern seaboard. The Nehantic Indians who once lived here might still recognize the place.

It’s hard to identify the exact point where you cross through the magic wallpaper into this world. But in past years, my work writing about wildlife often took away for weeks at time, to some of the more remote corners of the world. After the long return flight, worn down by travel, I drove south from the airport in Hartford, usually late at night, and I’d come to a half-forgotten point where the highway lights stopped. The sudden darkness always registered with a dull surprise, and then, after a mile or so for the eyes to adjust, stars appeared overhead. Oh. Yeah. My shoulders would ease down a notch, and the muscles around my heart would loosen, because I was home again.

By an odd quirk, the Connecticut River Valley itself could not figure out how to get here. For much of its long trip down from the Canadian border, the valley is a broad furrow of rich, relatively flat farmland. It’s defined on its eastern edge by big traprock ridges. But somewhere around Middletown, the ridgeline steers all that good, flat farmland away from us, southwest down to New Haven. The main highway, Route 91, goes that way, too, and good riddance. But roughly a half-million years ago, the river itself found a crack in the Mesozoic rock, and it now sneaks off to the southeast, spreading out and winding lazily down for the final 20 or so miles before it spills into Long Island Sound.

A geologic quirk also protects the lower river valley from the south: A grassy spit called Griswold Point stretches from Old Lyme toward Old Saybrook and then meanders underwater for much of the way across. This impediment to navigation prevented early New Englanders from turning the mouth of the Connecticut River into an industrial corridor. So what you see now when you sail up the channel from the Sound are mostly low, tree-covered hills, and, off to the east, the white spire of the Old Lyme Congregational Church rising above.

We first came here, like a lot of newcomers, because it’s so close to New York. You can get to midtown Manhattan by train in 2.5 hours. That’s too far to be practical for commuters, a good thing. But it’s close enough for the illusion of being in touch with bigger things and for me to re-connect from time to time with various editors. We stayed because it’s quiet, beautiful, a good place to raise children, and to hell with the bigger things.

I took up rowing unexpectedly in my late 40s, basically because there was a club in town, which made it easy. We rowed on a 260-acre dogleg of a lake, backed up behind a rickety old dam on a small tributary of the river. For years, when I wasn’t traveling, I went there most mornings before six, and it became an essential part of the pleasure I took in where I lived. Sitting on a slender single shell, I sometimes felt like a frog rowing a blade of grass, an image I found pleasing. It reminded me of Toad in Wind in the Willows. The people out rowing at the same hour—Water Rat, Otter, Mole, and the rest—became friends and made a happy change from my solo work as a writer.

Every row was a quest, not so much for balance, which came easily enough with a little forward motion, like riding a bicycle. Instead, when rowing a single, the search, generally futile in my case, was for a slower slide, better layback, and more speed. Rowing a double or a quad, the holy grail was to hit the water at the same microsecond, and at the same depth, drive smooth and strong, and then come cleanly out of the water and feather in unison. It was an aesthetic quest for synchrony, and there were hydroplaning moments when we seemed to skim over the surface with the water burbling past beneath the carbon fiber skin of the shell.

Even when we couldn’t quite find the secret code for that, though, there was the scenery: An osprey cruising with a freshly caught fish carried headfirst underneath, like a seaplane pontoon. Or a newly emerged damselfly riding on my deck for a lap and a half till its wings hardened enough for flight. I remember one frigid October dawn row, which started in the dark, with the full moon dropping down through the mist. Then the sun began to rise behind a hill. The clouds, still bruised nighttime-blue above, seemed to take flame from below. I sat up taller and my heart took wing.

Like every great place, the lower river valley is caught up in the destructive dynamic of its own appeal. Millions of people every year cross through the valley in a few minutes on Route 95 at Old Saybrook and never even know it’s here. But others stop in to visit for the first time as tourists. They catch a musical at the Goodspeed Opera House on the river in East Haddam, where the current attraction is generally a revival, or sometimes a revival of a revival. (The mindset here is trailing edge, with one foot dragging behind. But sensible enough never to vote for Donald Trump under any circumstances.) Or they have lunch at the Griswold Inn in Essex, where paintings of old sailing ships commemorate the area's long nautical history. Or they visit the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, billed as the birthplace of American impressionism. Then they notice the way the sunset picks out a lone sailboat beating its way up the river, and they make up their minds to come back and stay.

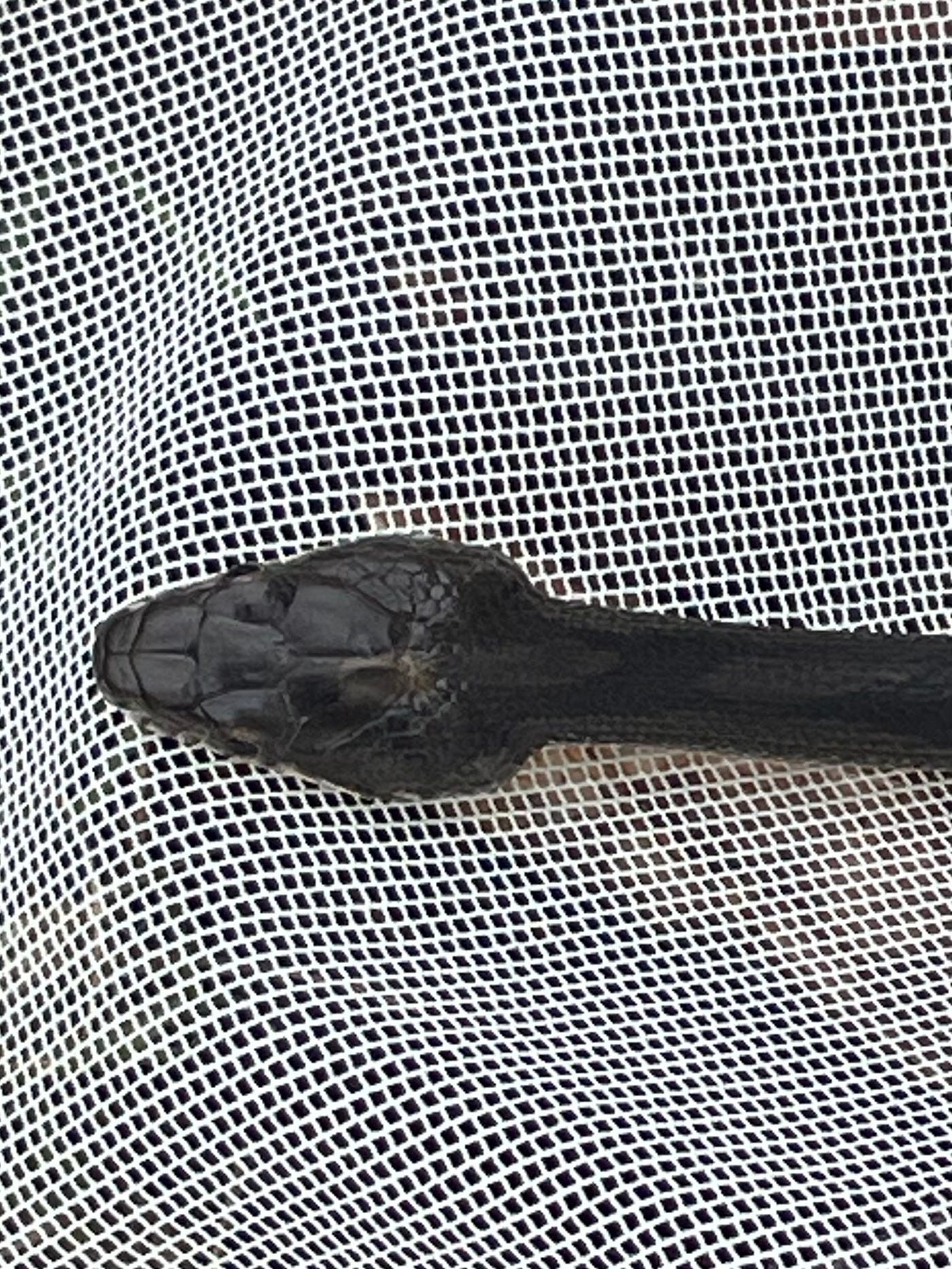

In the time-honored manner, newcomers work as hard as they can to keep other newcomers from following them through the magic wallpaper. It's selfish, to be sure. But a great place can absorb only so many people before it teeters over the edge into sprawl. So let me mention a few good reasons not to come here. First, we have large black snakes, which sometimes find their way into our houses. More about that on another day, but, anyway, I’m not kidding. If this sounds vaguely traumatic, perhaps you might consider building your monster home in Fairfield County?

We are also the birthplace of Lyme Disease, and we used to have two nuclear power plants nearby but one was decommissioned and later demolished. (The site is “fully remediated and ready for any use, including farming.” The small print: It’s likely to remain a storage site for radioactive materials for no more than the next 38,000 years.)

Besides that, the social life here is slow. Once in Louisiana, a Cajun asked me, “What y’all do for fun back home?” The question stumped me. For a time, new housing development along the lower Connecticut River was largely driven by Viagra (manufactured by Pfizer a little to the east) and gambling casinos (operated by Indian tribes, just north of Pfizerland). So it might have seemed that our corner of the “Land of Steady Habits” had taken a good-timey turn. But we were merely in the business of helping other people have a good time. Since then, Viagra has gone generic, and Pfizer has largely decamped to Boston. The casinos go clanging and glittering on, far enough away that you can pretend they don’t exist.

We have parties, but they are sedate. Friends of ours have a pillow in their living room embroidered with this sentiment: "Do not mistake tolerance for hospitality." But it's probably not quite fair to suggest that this is a good motto for the entire valley.

Messing about with boats, and houses, is a common pastime. So the local hardware stores are also an important part of the social scene. Being Connecticut Yankees and cheap, local people tend to calculate the cost of driving 15 miles to the nearest Home Depot, and realize it's almost never worth the gas, or the loss of local entertainment.

The hardware store is where you go instead, to buy essential nuts and bolts, of course, but also to bump into neighbors and find out if they have gotten the old Mustang off the cinderblocks yet (maybe next year), or if the bluefish are running on Hatchett Reef. Even at the height of the pandemic, when we were all obscured behind facemasks, the people behind the counter at Laysville Hardware, my local, just cattycorner to the rowing club, still instantly recognized regular customers by name.

But I suppose other towns also have their hardware stores. So in the end, it's the landscape and the wildlife that make the lower Connecticut River valley special. Traffic routinely stops here to allow wild turkeys, dark and sleek, to process in single file across the street. Sometimes a car slows down to ogle a fox trotting fearlessly along the side of the road with a squirrel in its maw. Osprey, almost wiped out fifty years ago, are everywhere now, plucking fish from the rivers and lakes. Bald eagles nest here in abundance.

The best way to see it is in a small boat, preferably human-powered. The fall, when Labor Day has passed and the summer madness is subsiding, is also the best season. The river comes alive then with the gathering flood of migratory wildlife, and the marshes and mudflats become staging areas for birds fattening up to make the long trip south over open water.

You can head out at dawn behind Selden Island, and see a kingfisher looping along the shoreline ahead of your bow. Or you can hit a certain island on the eastern shore on a late September evening, when huge flocks of tree swallows come swooping over the hills. They circle for a while high overhead, hesitating, until it’s almost dark. Then, as if on a signal, the flocks pull together into dense gray avian clouds, circle briefly, and come funneling out of the sky, pouring down to find their evening roosts among the phragmites reeds.

(On second thought, maybe you should skip that one, because it’s become a major tourist attraction. The motorboat traffic waiting on the outside of the island, in the open river, tends to become a great jostling fiberglass flotilla, fueled by gasoline, beer, and cocktails, which tends to kill the mood. And even on the quieter inside of the island, the last time I tried it, my kayak was one of about 100 or so others, including folks in lawn chairs on standup paddleboards. Nice folks, but more of them than I’d expected.

I prefer to recall a visit one October years ago at dusk, to a certain cove upriver. A friend and I angled our canoe into the shore, half-hidden among the reeds. Everything was quiet except for a light breeze making the wild rice rattle high overhead. Then the sky suddenly opened and the migrating ducks came pelting down for the night like a sudden rainstorm. After a few minutes, when they had settled down at a distance, we slipped quietly out of the reeds and found our way back to the river.

At times like that, you may realize somewhere in the back of your head that this is merely some point on the overdeveloped Eastern seaboard. Even so, the lower Connecticut River valley has a way of making you feel that you have found your way to the heart of the living Earth.

A gently, yet acutely observed piece. Thank you.

I was particularly taken by your neighbor’s needlework. "Do not mistake tolerance for hospitality."

Speaking with irony rather than judgement…in large swaths of the world - from Albania to Afghanistan - this notion is reversed:

“Do not mistake hospitality for tolerance.”

Wonderful! What a gorgeous, historic, and cultural place we live in :-)