'ave a Gin, Mate. The Water's Poison

An unlikely hero changed that. But, bloody hell, who needs public health!

by Richard Conniff

Adapted for these times from my book Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion (MIT Press, out in paperback next week!).

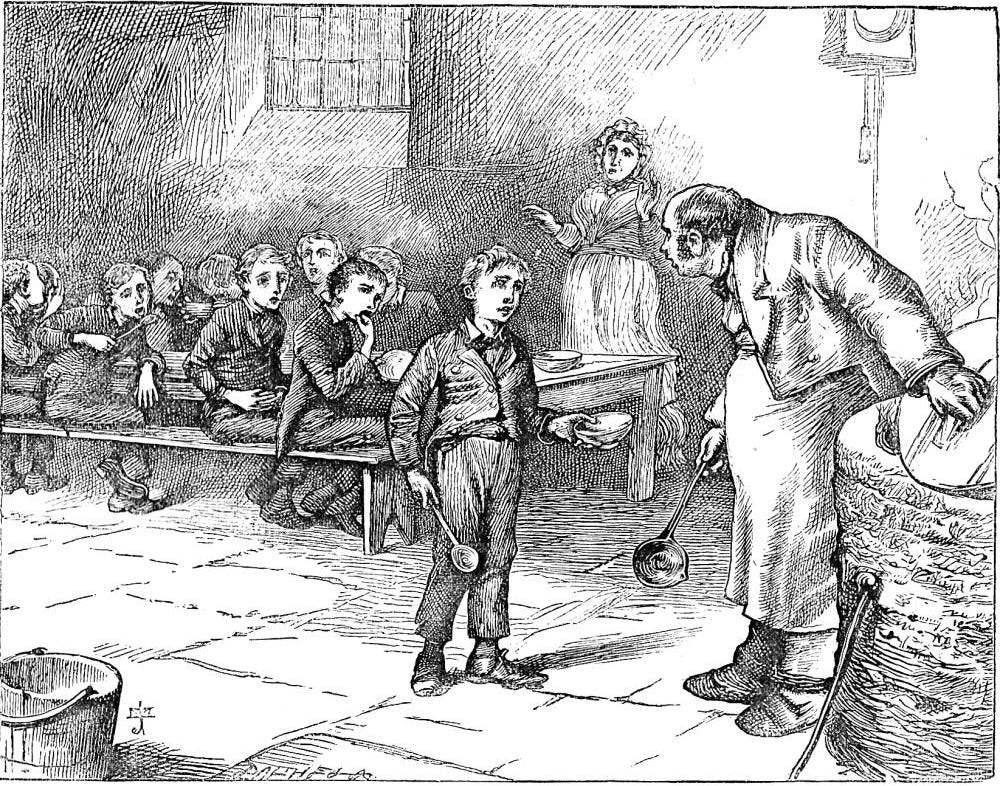

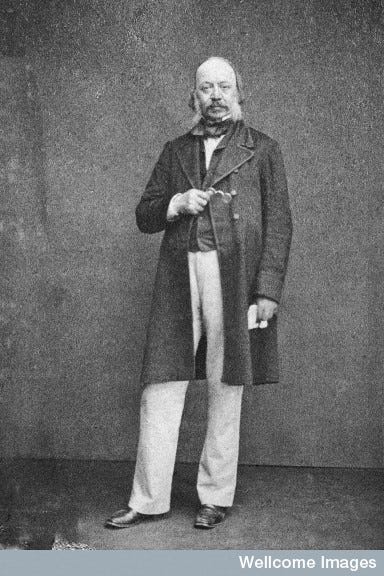

One of my least likely heroes was a quarrelsome, humorless, London barrister who, for a time in the 1830s and 1840s, made himself one of the most hated men in Britain. Edwin Chadwick earned his unfortunate early reputation working for a royal commission as a pioneer of the notorious workhouse system, where those who received public aid were confined in prison-like conditions. Charles Dickens, who loathed Chadwick, wrote Oliver Twist to expose this system’s cruelties. In the famous scene where Mr. Bumble whacks little Oliver in the head with a ladle for daring to want another bowl of gruel, it always seems to me that Bumble was just a stand-in for Chadwick.

Some hero, right?

But Chadwick learned from his mistakes and went on to introduce some of the greatest public health reforms in modern history, saving countless lives not just in Britain but around the world, where his sanitary reform movement soon spread. He also played a large part in developing the original model of a centralized civil service separated from commercial considerations and focused instead on protecting the public welfare—just the sort of system that Donald Trump is now furiously aiming to destroy.

The challenge in Chadwick’s day was that the factories of the Industrial Revolution were packing old cities with newcomers, overwhelming the available housing and the adjacent, and often uncovered, cesspools. Entire families commonly huddled together in single rooms and windowless basements. London, like other cities, increasingly used the river on which it was built for both sewage disposal and drinking water.

Disease was the inevitable result. But no one responded to the problem at first because public health was then outside the purview of national government. People also failed to recognize the developing scale of the problem, or they imagined that it would affect only the poor.

In 1838, a devastating outbreak of typhoid, a waterborne disease, sickened 14,000 people in London alone. In the aftermath, Chadwick arranged for the Poor Law Commissioners to have three prominent physicians investigate public health and poverty in London. Their report caused a sensation for its depiction of the city’s grossly unsanitary system of water supply by private companies. The Commissioners then assigned Chadwick to conduct a similar investigation into the sanitary conditions in which the laboring classes lived nationwide. They provided no funding.

Chadwick undertook a prodigious correspondence, asking doctors and Poor Law officials across the country to answer a list of detailed questions. His passion for gathering evidence with his own eyes also made him a determined explorer into British slums, recording how the poor lived and died. The result was such a dire and unsparing picture of a nationwide public health emergency that his timorous employers demanded changes and ultimately declined to put their names on it.

Thus one of the most important works in the history of public health carried only Edwin Chadwick’s name when it appeared in 1842. The Sanitary Report—short for Report on The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain--was an odd publication to come from the government’s own Stationery Office, “a masterpiece of protest literature,” in the words of one historian, weaving together “the most lurid details and evocative descriptions, damning statistics and damaging examples.” It sold 100,000 copies, more than any previous government publication.

For most educated readers, the world of the urban newcomers of the Industrial Revolution had been as foreign as Calcutta. Chadwick’s report led them deep into the squalor they had previously passed by with eyes and noses averted. On one “perambulation” through the narrow lanes and courtyards of a fever-ridden Glasgow neighborhood, he described open dung heaps piled high “with all [the] filth that the swarm of wretched inhabitants could give.” In a neighborhood in London, “every article of food and drink must be covered,” he wrote, lest swarms of houseflies attack it and render it unfit for use, “from the strong taste of the dunghill left by the flies.”

Chadwick built his report as methodically as a legal brief. He focused on the devastating cost of existing sanitary conditions to the economy, in lives and workdays lost. He also made detailed recommendations, including public control of the water supply and sewerage systems, which needed to be properly pitched to flush wastes well away from crowded populations. He presented evidence that such sanitary measures could improve health and longevity at reasonable cost, and he reviewed the state of existing law and of the local authorities responsible for administering it.

Chadwick also made shrewd use of medical statistics, a science then in its crude early stages. He compared the decreasing mortality in one East Anglia town that installed sewers with the rising death rate in a similar town nearby that continued to rely on open cesspools. Even more effective was a section, with tables and maps, showing the variation in death rates in different social classes within the same communities. In Bethnal Green, in London’s East End, the average age of death for “gentlemen and persons engaged in professions, and their families” was 45, but for tradesmen it was 26, and for “mechanics, servants, and labourers,” just 16.

Chadwick’s neighborhood-by-neighborhood, and street-by-street, comparisons foreshadowed the modern environmental justice movement. And he was plainly moved to outrage by the complacency with which the “better classes” tolerated and even tacitly applauded the endless dying. A common view held that a high death rate among the poor benefited society by providing a Malthusian check on population. To the contrary, Chadwick recounted a visit to a crowded neighborhood notorious for its high mortality rate. “Why, the undertaker is never absent from this place,” he remarked to a local woman. She looked out over a courtyard full of underfed children and replied, “No, nor the midwife either.” Chadwick correctly concluded, “that the ravages of epidemics and other diseases do not diminish but tend to increase the pressure of population.”

Charles Dickens became a convert, and echoed Chadwick’s message in both his fiction and his weekly magazine, “Household Words.” In one article there, he sounded like Chadwick unchained, on the “intolerable ills” arising from the terrible living conditions of the poor: “A Board of Health can do much, but not near enough. Funds are wanted, and great powers are wanted; powers to over-ride little interests for the general good; powers to coerce the ignorant, obstinate and slothful and to punish all who, by any infraction of necessary laws, imperil the public health.”

No laws were passed at first, and Chadwick was instead assigned to prepare additional reports. But one such report, this time signed by all thirteen eminent commissioners, provided a comprehensive program for reforming towns and cities to improve the health of their residents.

The recommendations included provision of a constant supply of water to all homes and businesses, together with a system of sewers and drainage, all under the direction of a single administrative body for each locality. The aim was to provide a continuous “arterial-venous” flow of water into cities for daily use, and out again, carrying away wastes. Local governments would have power over the removal of rubbish, widening, paving and cleaning of streets and pedestrian walkways, regulation of the design, construction, and ventilation of buildings, and the appointment of a local medical officer to inspect all such matters of public health. The report also recommended a way for local property owners to pay for these improvements without bankrupting themselves, by amortizing the costs over years or even decades.

The report also recommended a national authority to inspect and supervise sanitary improvements This had always been Chadwick’s ambition, given his faith in the value of a centralized civil service, aloof from petty local interests. It fit with the abundant evidence he had accumulated, at the local level, of indifference, incompetence, corruption, and favoritism of wealthy interests over the needs of the poor. It was altogether a broad endorsement by the establishment for radical transformation in the way cities operated.

It took another three years of political infighting to win approval of the Public Health Act of 1848, which established a weakened version of the central oversight body Chadwick had imagined. By hard lobbying, he won appointment as the only salaried commissioner of the three assigned to run the board. His six years in that post “were the happiest in his official career,” according to biographer R.L. Lewis. At his office in the heart of Whitehall, he gladly worked 12- or 14-hour days “sending out his Inspectors to put chastened local authorities on the cleanly path of tubular sewerage and constant supply.”

This was bound to be hard work, against forces characterized by one historian as “parsimony compounded by ignorance and fear of engineering innovations.” The reforms he was advocating were daunting in their scope for local officials and engineers who had never imagined water supply and sewer systems planned and built out across an entire town or city, much less across a natural topographic drainage.

Then as now, they resented outside interference and were capable of saying almost anything to defeat it. In 1846, a delegation questioned the Lord Mayor of London about the approaching threat of cholera. The squalor Chadwick had detailed remained entirely unchanged. But the Lord Mayor assured his interrogators that “there could be no sanitary improvement effected in the City of London.” It was, he said, already “perfect.” The cholera epidemic of 1848-49 suggested otherwise, killing 15,000 London residents.

In the General Board of Health’s first five years of work under Chadwick, 284 municipalities petitioned to be recognized under the new Public Health Act, another 126 conducted drainage surveys—the first step toward a proper sewer system— and 31 municipalities finished their plan and received approval to seek the necessary financing. In some cases, work had begun. This no doubt seemed like a slow start to the notoriously impatient Chadwick. But it was still a novelty for any government to do anything at all about public health—much less do it at the mandatory expense of private property owners.

The new water and sewerage systems proved themselves “novel in design, cheap to construct, and efficient in operation, bringing the means of health and cleanliness down to a weekly charge of a few pence” per house, R.A. Lewis wrote. “But greater than the economy of money which resulted was the economy of life.” The General Board of Health reported in 1853 that replacing cesspools with sewer pipelines in London’s prosperous Lambeth Square had caused the annual death rate to fall from 30 to 13 per thousand.

Sanitary improvements had also halved the death rate in certain unnamed working-class areas. The board projected that the same improvements would prevent 25,000 needless deaths per year if applied across London, and 170,000 across England and Wales. The average age at death would climb from twenty-nine to about forty-eight.

But Chadwick’s career as an executive was destined to be brief. He had been making bitter enemies since Poor Law days, and too few friends. He had criticized physicians for dithering about the true cause of disease and promoting bogus cures. He had implied that civil engineers who disagreed with him were incompetent or corrupt. He had fought with undertakers and burial insurance schemes for robbing the poor, with private water companies for poisoning their customers in pursuit of short-term profit, and with shopkeepers and small businessmen for being fixated on keeping down their property taxes, even as the cost in human lives became more evident. Being adamantly in the right didn’t necessarily help.

In 1854, Chadwick resigned under pressure. For Chadwick, it was the end of his life as a public servant. But he left behind a rapidly professionalizing civil service that had begun to grow up and gradually displace control by special interests and the upper classes. Chadwick’s sanitary reform movement would live on and spread to cities worldwide.

The work he began still needs doing, of course. Maybe it always will. And until recently, the United States actively participated in it, through the WHO, USAID, the CDC, and other public agencies working to bring safe drinking water, proper sanitation, and basic medical care to neglected areas. We had a body of civil servants who devoted their lives, one way or another, to fulfilling the dictum of Chadwick’s own teacher Jeremy Bentham: that doing the right thing means doing what produces “the greatest happiness for the greatest number.”

But that seems to be over now. Instead, our government is in the hands of oligarchs, who care about the “greatest number” only if it’s in their own bank accounts. For them, keeping waterways clean, reducing air pollution, protecting people against infectious disease, defending democracy, and other such government business are just wasted tax money, and needless interference in their own prosperous endeavors.

They may prevail. But if we let them, we can expect, as in London in the 1840s, that a river of filth, neglect, disease, and dead bodies will follow.

Richard Conniff’s Substack is not funded by cowardly billionaires, corporate sponsors, or advertisers. I depend on support from readers like you. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

As of yesterday, thanks to a new Supreme Court decision, dumping sewage in open waters is back, baby, in the USA. The decision curbs the ability of the Environmental Protection Agency to set limits on water pollution. In Chadwick's home country, Parliament has also declined in recent years to ban combined storm-sewer discharge into rivers, or to establish a system of automatic fines. Swim (or drink) at your own risk. https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/04/politics/supreme-court-san-francisco-poop-epa/index.html?utm_campaign=mb&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_source=morning_brew

Many thanks for sharing, and for highlighting the parallels with the catastrophic decisions that have been taken by Agent Orange over the past month.