My Neighbor Is a Snake

There's an entertaining reptile hereabouts. Probably where you live, too.

by Richard Conniff

I promised this story in a post a few weeks ago. Shockingly, no one has been clamoring for me to publish it. But you, bold reader, have made it this far. Read on for an experience on the farther edges of peaceful coexistence and living with wildlife.

Years ago, in the three-story stone house my wife and I had purchased, I was puzzled to find shed snake skins in the attic, 27 feet off the ground. They were common in attics locally, I soon learned. In basements, too, and not just their shed skins. The family next door had a bathroom on the ground floor, which was built into a slope. Their toddler once went in and found a live snake sedately coiled in her potty seat.

This was of course horrifying for us as city dwellers new to the country, and possibly also for the toddler. The snakes were black and up to six feet long, and it was always startling to take logs off the woodpile or lift the lid from the compost heap and find one underneath. Or worse. One time, I was demolishing the door frame on the root cellar, when the rotten lintel gave way overhead, sending two fairly large black snakes wreathing down around my ears, onto my shoulders, and then as as far away from me as they could get.

What happened next will seem improbable to those who suffer from a deep, unshakeable fear of snakes. From horror, I began to rationalize, because we liked living in an old house in the Connecticut River Valley. And gradually my feelings about these particular snakes evolved into something like neighborly tolerance, even friendship. It did not happen all at once but gradually, as these same snakes have turned up at--and sometimes in--various houses we have owned hereabouts over the years.

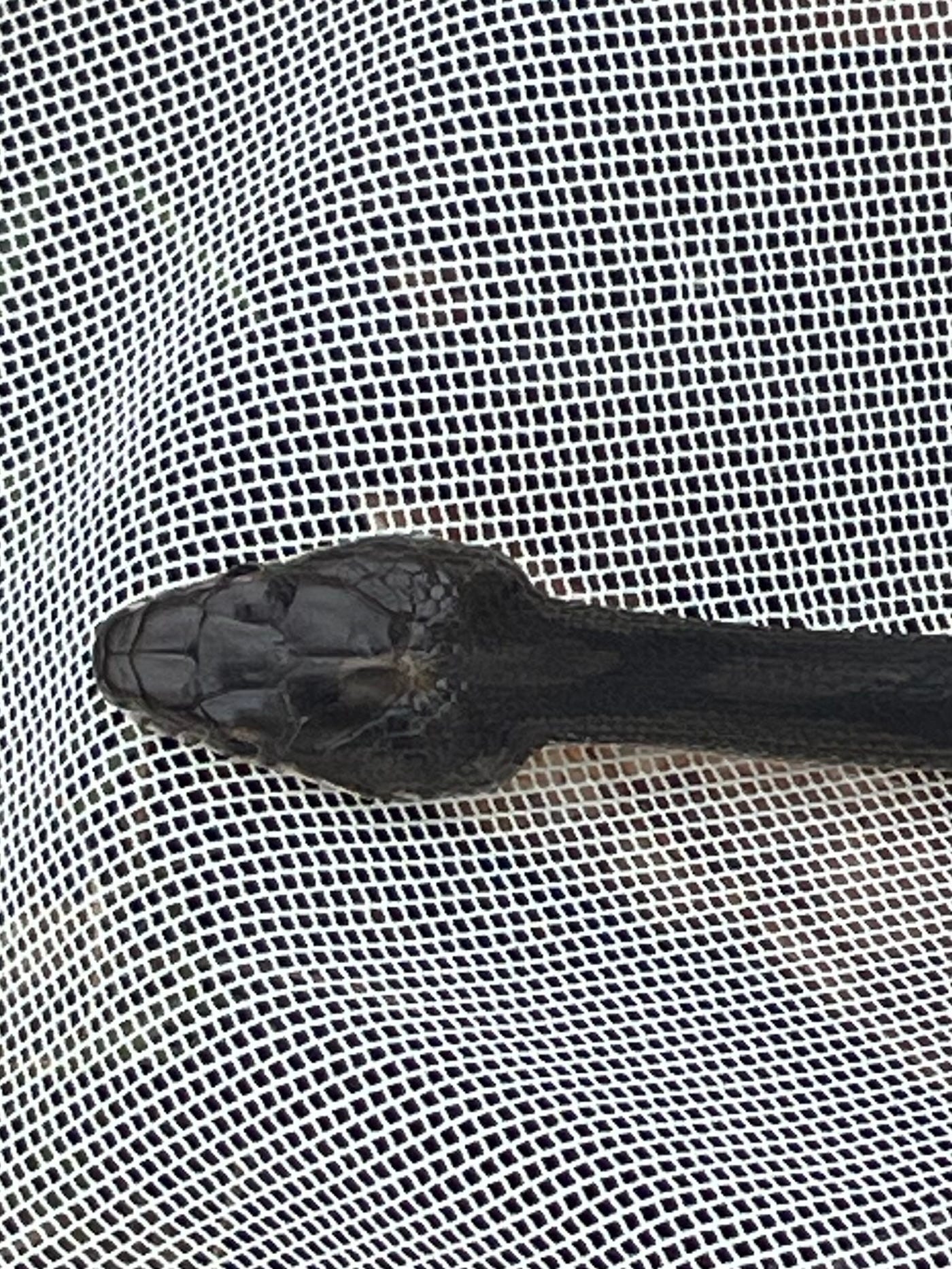

The proper name for the species is the eastern rat snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis), and they are common from Florida north to the Great Lakes. Including the closely related western rat snake, their range extends west into Kansas and Texas. So, yes, if you live in the eastern half of the country, and parts of Canada, too, you probably have them in your neighborhood. The good news: They are non-venomous and generally unaggressive, except in ways we mostly consider beneficical.

Farmers gave them their common name for their ability to keep down rats in the barn. We started tolerating them for similarly practical reasons, to discourage chipmunks from raiding the garden, house mice from getting indoors, and deer mice from bringing Lyme disease into the yard. It’s true that rat snakes will also eat young birds in the nest, for which many people loathe them. But their predation is part of the natural ecology of the habitat, unlike, for instance, the considerably greater damage done by outdoor house cats. Moreover, the nesting season for birds is short. Rodents, on the other hand, are everywhere and always.

Despite the unfortunate name, rat snakes are beautiful creatures. They don’t slither, they glide, and there is a kind of forthrightness about it. They do not seem to be in any great hurry as they travel in search of their next uncertain meal, nor do they have any apparent need for camouflage or other forms of disguise. They appear to be at home in their own skins and in their world.

Coming home one summer evening a few years ago, I saw a rat snake in the front yard with its head down a mouse hole and the rest of its body casually sprawled across the lawn. I worried briefly about hawks and other potential predators, but refrained from offering advice. Next morning, as I was heading out at dawn, I spotted the snake again halfway out of the same hole, head up this time. It was periscoping around, un-alarmed by my presence. It felt as if we were companions in our common business of sorting out the new day’s prospects.

I thought of a poem D. H. Lawrence wrote during a Sicilian idyll, on finding a snake ahead of him at what he had come to think of as his watering place. It was a venomous species, and his cultural training said that killing such snakes is what a man should do. And yet Lawrence refrains: “Must I confess how I liked him,/ How glad I was he had come like a guest in quiet to drink at my water trough/ And depart peaceful, pacified, and thankless …” But when the snake turns away, retreating to its underground home, Lawrence yields to culture and flings a log ineffectually at the snake’s vanishing tail. He is instantly remorseful, having “missed my chance with one of the lords/ Of life.”

The reality of course is that Lawrence was the guest, and so am I. Rat snakes have lived on what I think of as my property since long before the first human inhabitants of this land. Individually, they also enjoy surprisingly long lives, up to 25 years, and they know the nuances of the land far better than I ever will. They typically occupy a home range from a fraction of an acre to several dozen acres in size, depending on the available resources. They spend their days—or nights when it’s warm enough—roaming more or less randomly across this territory, sleeping on a tree branch or in a snug spot under a rock, and taking their pleasure wherever they happen to find themselves.

A neighbor working in her yard on a hot, dry day last summer heard splashing overhead. She looked up to see a rat snake bathing in a tree hole puddle 30 feet up, with its tail hanging out, at ease. If it were anything other than a snake, it could be one of those whimsical animal creatures in a children’s book.

“But how did the snakes get up into our attic?” I asked not long ago, still thinking of that 27-foot-high stone wall at our first house. I was on the phone with Patrick J. Weatherhead, a retired herpetologist, who studied rat snakes at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“The more intriguing part to me is how they come down,” he replied. The snake’s scales point in the direction of the tail, and it is easy enough to flare them out as highly mobile pitons for climbing up a tree, or along the grout lines of a vertical stone wall. (Here’s a video of one climbing a tree.) To come down, said Weatherhead, rat snakes benefit from having bodies that are squared off on the bottom like a bread loaf. They seem to manipulate the angle where the side and belly scales meet to cling to tiny crevices and go down headfirst as confidently as they went up.

The snakes don’t come into our houses to stay warm in winter, as I had assumed. For the winter, Weatherhead said, they make a beeline back to a local den they may share with a half-dozen of their fellows. There, they brumate, which means that the metabolism slows down, as in hibernation, but they remain alert. Scientists call their winter shelter a hibernaculum, though “brumatorium’ would be a much cooler word.

Our houses mainly attract them in summer, because adult rat snakes must shed their skins several times then. As the skin begins to separate from the body, the scales, including the ones over the eyes, turn a cloudy blue, leaving their vision compromised. They go into attics, basements, and other places to find refuge. It is a mark of trust, and I suppose for that moment, our roles are reversed, and they become our guests.

In any case, finding their shed skins has become a sign of good luck for us—though we do not knowingly invite them into the house. One Sunday morning this past spring, my wife left a door open for a bit to enjoy the change of seasons while she made pancakes. A few minutes later, she looked around and found a young rat snake there on the kitchen floor, considering where to go next. It had evidently slipped out of the woodpile by the door. It waited patiently as I retrieved a net to pick it up. (You will see folks online grabbing them by the hand, but I am not one of them.) I carried it back outside to a good spot in the yard, where I sent it on its way.

It was all very low key. Then I closed the door and we sat down to pancakes.

Afterward, because there are limits to even the best friendships, I relocated the woodpile.

Richard Conniff’s latest book, Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion, is now out in paperback. His other books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W.W. Norton), Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World (Henry Holt), and Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time—My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals (W.W. Norton). He is a National Magazine Award-winning feature writer for Smithsonian, National Geographic, and other publications, and a former contributing opinion writer for The New York Times.

OTHER READING AND VIEWING

Check out this video on rat snake climbing.

What a lovely essay on overcoming primordial fears to reach appreciation and moving through the wonder in daily life! Thank you for writing this, Richard! All Best from Loa Angeles

Fun read, thank you! It's fun to see rat snakes' kinked bodies on the wall or taking some sun in the grass. Of course, here in SE NC, rat snakes (and ropes, garden hoses, etc.) are regularly mistaken for copperheads. Not that any snake should have to fear the shovel!