This week—tomorrow, March 26, in fact, my favorite natural history museum reopens, after four long, painstaking years of rebuilding and renovation. The Yale Peabody Museum has already revolutionized dinosaur science twice in the 108 years since paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh founded the place in 1876. In my book House of Lost Worlds, I tell the story of the museum, from Marsh’s great discoveries in the American West (Allosaurus, Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Diplodocus and many, many more) on up through the “dinosaur renaissance” of the 1970s, driven by the Peabody’s John Ostrom and his discovery of the bird-like dinosaur Deinonychus.

To celebrate the re-opening, I’m going to post this week about one of my favorite characters from the book, the often un-credited and sometimes unpaid paleontologist behind many of Marsh’s most famous discoveries.

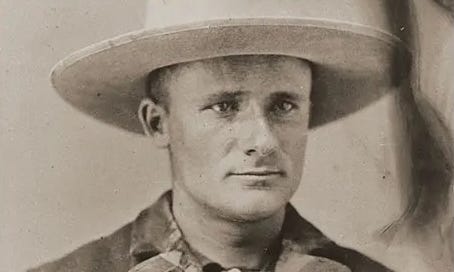

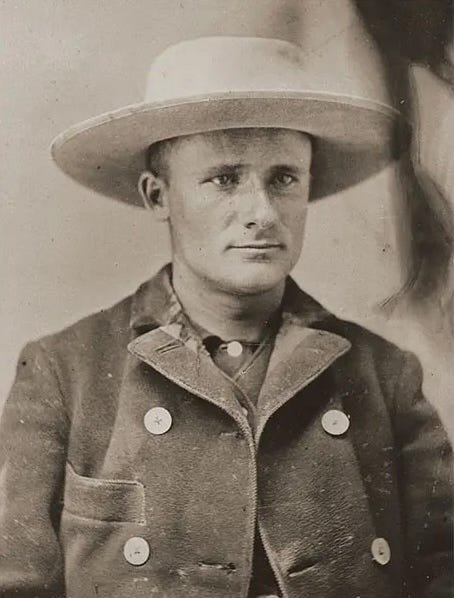

Late in 1888, John Bell Hatcher, bone hunter, was traveling alone through southeastern Wyoming. His high forehead was hidden beneath a slightly oversized white Stetson, which made his deep-set eyes seem even deeper, the brows slanted down to the outsides, the lips thin and expressionless. His wide face lent him air of both Midwestern guilelessness and quiet competence to handle whatever came his way. He looked like—and was rumored to be--an excellent poker player. (His face, according to paleontologist Barnum Brown, was “inscrutable, and you never knew whether he had a bob-tail flush, or a full house.”) Poker was, among many other things, a handy means of striking up friendships and trading small talk as he traveled through the Deadwoods and Laramies of the developing West.

In Jordan, Wyoming, one day, the talk turned to a huge skull some cowhands had found three years earlier, which a rancher named Charles Guernsey described as “sticking out midway of a bank on one side of a deep dry gulch,” with “horns as long as a hoe handle and eye holes as big as your hat.” Guernsey and his cowhands had tried to dig it out of the sandstone bluff, neglecting to lasso it like a stray head of cattle, with the result that they tumbled it down to the bottom of the ravine, almost taking Guernsey down with it. He had taken away only a fossil horn core—the horn minus its eroded exterior sheath.

At Hatcher’s request, Guernsey sent it on to New Haven for inspection that winter. It was eight inches across at the base and almost 20 inches long. That made Hatcher and Marsh both question Marsh’s recent attribution of another fossil horn core to a species of ancient bison. Marsh was “immediately possessed with a burning desire” to obtain the skull and identify the geologic strata from which it came. Early that May, under heavy pressure from Marsh, Hatcher left his wife Annie, who had lost their first baby just two weeks earlier, and headed to the scene, 30-some miles north of Lusk, Wyoming.

“The big skull is ours,” he wrote, just three days later, with characteristic efficiency. The fragments filled four large boxes and weighed about 1100 pounds. It was a small sample of the much larger discoveries lying just ahead, as Hatcher hunted down one of the most celebrated creatures in paleontological history.

Hatcher had grown up in Iowa and attended Grinnell College there for a year before transferring to Yale. He earned money for college working as a coal miner, and the fossils he saw as he dug had stirred his interest in paleontology and eventually brought him to Marsh’s attention. Within days of Hatcher’s graduation in 1884, Marsh sent him off, with funding through the U.S. Geological Survey, to start an apprenticeship under Charles H. Sternberg, founder of a Kansas empire in commercial fossil collecting. But Hatcher had strong ideas and an astounding sense of self-reliance. He thought Sternberg was overlooking valuable specimens and could save others “by taking more pains” in digging them out and packing them. One day, after Sternberg had repeatedly failed to pacify the troublesome owner of the land where they were digging, Hatcher discerned the true nature of the difficulty and hired the landowner as an assistant. Then the two of them moved off to the opposite site of the ravine from Sternberg.

The first report Hatcher sent to Marsh, just four days later, showed the site carefully divided into sections and mapped out, much as a modern paleontologist would do, and with the position of each of the 67 bones he had removed from one section precisely located on a separate diagram. Hatcher’s prodigious career as an independent collector had begun.