by Richard Conniff

This is the third episode of my profile of John Bell Hatcher, fossil hunter, excerpted from my book “House of Lost Worlds,” a history of the Yale Peabody Museum, which re-opens this week after a four-year closure for renovations. Here’s a link to Episode 1 and Episode 2.

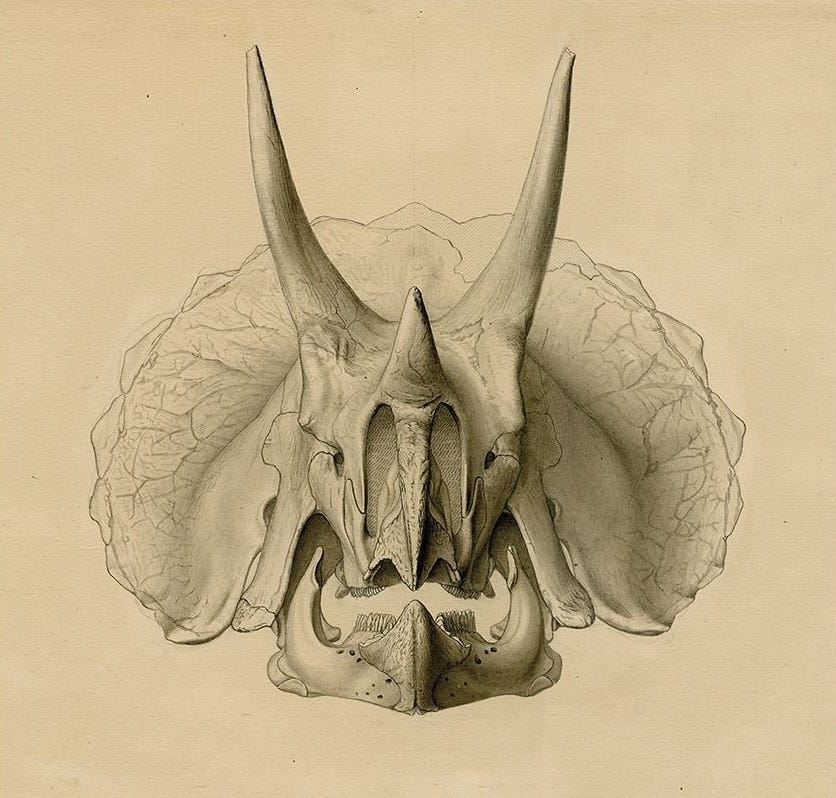

The skulls Hatcher was finding, measuring six or eight feet in length, belonged, to Triceratops, as Marsh named the genus in a November 1889 article. That article gave a brief nod to Hatcher in its final sentence, an unusual gesture for Marsh, who otherwise recognized Hatcher’s talent mainly by sending him to work in northern regions for nine months of the year, and southern ones for the other three. As with all his collectors, Marsh also routinely kept him on a short budget (though Hatcher is said to have supplemented this budget with poker winnings). Hatcher’s letters from that period are full of amazing discoveries, alternating with pleas for payment of past-due expenses.

Though he was ostensibly earning $300 a month for wages and incidental expenses, he calculated that he had cleared just $80 in July 1889. August was worse. After paying to freight two huge skulls back to New Haven, “I will be about $8.00 worse off than if I had not dug bones at all this month.” In case Marsh did not get the point, he added, “In other words, I pay $8.00 for the privilege of working a month and furnishing an outfit [the wagon and horse team] that has cost me over $500.” He had not seen his young and grieving wife since May, and he wrote, “I have been”—he crossed out what seems to have been an “f” for “failing”—“disappointing people all summer.”

Hatcher wanted a chance to become not just a collector, but a scientist describing his own finds. He also yearned for the privilege of leading a normal domestic life, for at least half the year. (“A letter from Long Pine tells me we have another young bone-hunter at our house,” Hatcher wrote Marsh, when Annie Hatcher gave birth in August 1890 to their second child. “I hope he will live longer than the other one did.”) Hatcher asked repeatedly for a permanent salaried position, preferably at the Peabody or at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum. Either would have allowed him to work with specimens he had collected for the U.S. Geological Survey.

Failing that, he asked Marsh for a recommendation to help him obtain such a position elsewhere. Instead, Marsh seems to have said just enough to muddy the waters with any prospective employer. (To be fair, one of the people trying to hire Hatcher away was the Cope ally and virulent Marsh-hater Henry Fairfield Osborn.) In 1891, Marsh agreed to a contract that gave Hatcher a $2000 annual salary as assistant in geology, with no more than six months a year in the field. But this was a fiction. The two finally broke off their connection in 1893, after funding from the U.S. Geological Survey ended. Hatcher moved to a position as curator of vertebrate paleontology at Princeton, where he worked under the Cope ally and Marsh-hater, W.B. Scott. Later, he switched to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh.

But once a Yale man, always a Yale man. Hatcher’s letters from the field included regular requests for news of the college crew team. His adventures as a bone hunter--his daring, his determination, his unshakeable integrity, and even his ability to handle playing cards or a gun--made the pulp fiction Yale heroes of the day, the Dink Stovers and Frank Merriwells, look like the palest shadows of what a man could be. In any case, Hatcher’s connection to Yale and the Peabody would be renewed long after his death, largely through his work at the other end of the hemisphere, in Patagonia.

Hatcher made three heroic expeditions there in the 1890s, in search of Mesozoic mammals. These trips involved traveling on horseback, alone or with one or two companions, for hundreds of miles through horrific winter weather, in the face of repeated warnings from locals that he should not go. But “we had tented it for many years on the wind-swept plains of Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas,” Hatcher wrote, “often with the thermometer far below zero, and had no uneasiness as to our ability to survive successfully whatever blizzards Patagonia might have in store for us.” He was underestimating Patagonia. At one point on the second expedition, he crawled into his tented crippled by a combination of fever and rheumatic swelling of arms and legs, but expecting nonetheless to resume his journey in a day or two.

“Such was not to be the case,” he wrote, “for the rheumatism, together with the accompanying fever, rapidly increased in severity and soon spread to my hands, feet, neck and left hip. For six weeks I was absolutely helpless and unable to shift myself in bed or attend to my most trivial wants.” Another member of the expedition kept him alive. Then they went back to collecting.

(To be continued)