This week I’m saluting the re-opening of the Yale Peabody Museum, after a four-year closure for rethinking and renovation. Today’s episode, excerpted from “House of Lost Worlds,” my history of the museum, tells the harrowing story of John Bell Hatcher’s work in Patagonia. Here are links to Episode 1, Episode 2, and Episode 3.

by Richard Conniff

On another expedition in Patagonia, Hatcher set out alone with his horse on a 125-mile trip through horrible weather to ensure that the tons of fossils he had collected were properly loaded into a ship bound for New York. He was an experienced horseman, but during a break on the third day, his horse caught a hoof through the reins. As Hatcher stooped down to free it, the startled horse jerked its head violently upward, then down again, driving “the broken shank of the Logan bit with which the bridle was fitted … through and under the scalp,” tearing the skin loose “over a considerable area.”

Hatcher used his hand in a sort of comb-over to lay his scalp flat again on his skull, bathed his head in cold water, then mounted his horse and rode on with blood pouring down his chest and saturating his clothes. Feeling faint after a few hours, he dismounted, wrapped a couple of handkerchiefs around his head, rammed his Stetson down around them, and lay down for the night with his saddle for a pillow.

When he reached a ranch the next day, he asked for food and some soap and water to clean his wound, but the cook (“a surly Italian”) told him to move on. Hatcher showed the money he was ready to pay for any help, to no avail. But he had a way of getting what he wanted. (One time in Punta Arenas, he and another paloentologist saw a horse dealer beating a horse “with the loaded end of his quirt.” Hatcher drew his revolver and said, “Beat that horse once more, and you’ll be a dead man.” He did not need to shoot.)

Now he pushed past the cook (“this ‘dago’”) to the kitchen and sat down to a meal of bread and cold mutton. He built up the fire in the stove, made coffee, and bathed his head in warm water long enough to loosen the Stetson and handkerchiefs. When he was done, he left the absent proprietor a note offering to pay for everything on his return trip. Then he rode twenty-five miles onward and spent another cold night on the ground. When he eventually arrived at his destination, Hatcher secured his specimen crates, which were of course not being handled to his satisfaction. He also took his suppurating head wound to the local doctor, who recommended bleeding. Hatcher chose to treat himself instead.

All this naturally made an impression on the Patagonians, and an American oil executive who traveled through the region in Hatcher’s aftermath recounted his reputation, embellished perhaps in the best “print the legend” tradition. Writing decades later in The Atlantic, James Terry Duce described Hatcher as “a rather subdued-looking American scientist” who taught lessons in poker in “every hamlet from Bahia Blanca to the Straits,” and “as a rule the loose change of the community passed on to the bone hunter to be spent on science.” The gambling ended when “the whole countryside dropped in to exact revenge” shortly before Hatcher’s return home. “The stacks of pesos in front of Hatcher climbed up and up until he was almost hidden behind them; the whistle of the steamer sounded down the harbor. Hatcher announced that he must go. Someone suggested that they would not let him. He picked up his gun and his pesos and backed through the door with a ‘Good night, gentlemen!’ No one made a move. The wind whooped round the eaves and Patagonia went back to its sheepshearing with a wry smile on its face.”

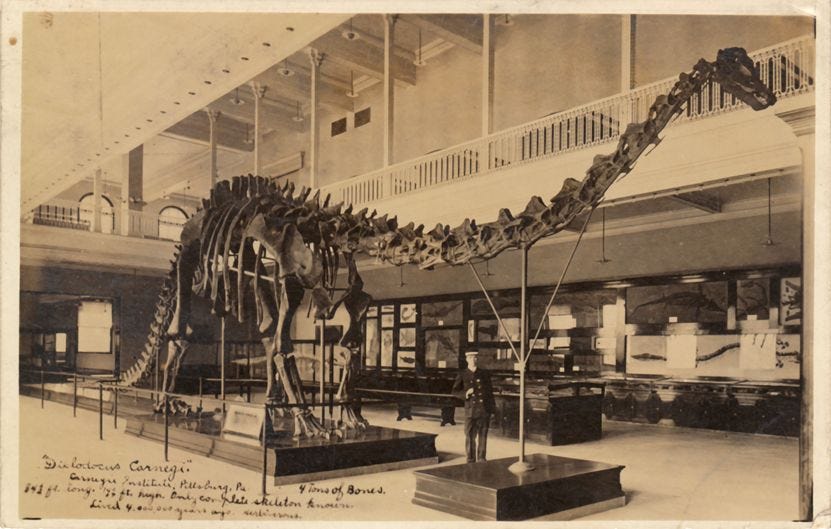

Hatcher’s own memoir of his time in Patagonia, Narrative Of The Expeditions: Geography Of Southern Patagonia, makes no mention of poker, though it is otherwise a thrilling account. He dedicated it, on publication in 1903, not to his poor, patient wife Anna but to O.C. Marsh, “Student and Lover of Nature,” the bitter feelings from his years in Marsh’s employ having faded. In the decade after leaving Yale, he had published 48 scholarly papers on fossils and geology, and his Patagonia discoveries had become the heart of Princeton’s vertebrate paleontology collection. At the Carnegie, he created the first museum mounting of a complete sauropod, Diplodocus carnegii, with a copy mounted soon after at the British Museum.

Decades later, in 1985 Princeton decided to close down its paleontology program and, after considering applications from the Smithsonian, the American Museum of Natural History, and other major institutions, elected to donate its entire collection to the Peabody Museum. When news reached him in the afterlife that his own specimens would end up in O.C. Marsh’s museum, Princeton’s W.B. Scott no doubt died again. But Hatcher might well have been content to see so many of his brilliant discoveries united in one place, where they continue to be studied by scientists from around the world. Hatcher himself died of typhoid fever at the age of 42, leaving his wife Annie too soon, as he had always done, and with four young children. He was buried in a grave that was, until recently, unmarked.